Research Highlights

Oceanus Magazine

News Releases

Filter-feeding whales sample the Arctic food web, tracking decades of change

Differences in brain structure between echolocating and non-echolocating marine mammals offers insight into auditory processing

WHOI researchers part of collaborative, international effort to increase Marine Protected Areas and other strategies

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and partners take home prestigious award

Long-awaited event sets the stage for scientists to learn more about physical, chemical and biological processes in the deep ocean East Pacific Rise, Pacific Ocean (May 2, 2025) – Scientists diving in the human-occupied vehicle Alvin recently witnessed a rare…

News & Insights

April 24 marks the first-ever Right Whale Day in Massachusetts. WHOI biologist and veterinarian Michael Moore recently met with the resident who brought this special recognition about– and explains why it’s important to raise awareness about the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale.

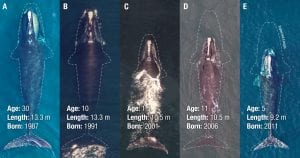

A report out this week in Current Biology reveal that critically endangered North Atlantic right whales are up to three feet shorter than 40 years ago. This startling conclusion reinforces what scientists have suspected: even when entanglements do not lead directly to the death of North Atlantic right whales, they can have lasting effects on the imperiled population that may now number less than 400 animals. Further, females that are entangled while nursing produce smaller calves.

May 10, 2021 During a joint research trip on February 28 in Cape Cod Bay, Mass., WHOI whale trauma specialist Michael Moore, National Geographic photographer Brian Skerry, and scientists from New England Aquarium, witnessed a remarkable biological event: North…