Five marine animals that call shipwrecks home

One man’s sunken ship is another fish’s home? Learn about five species that have evolved to thrive on sunken vessels

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

When it comes to the relationship between humans and marine life, it can be far easier to see ourselves as passive beneficiaries of the ocean rather than active members of this ecosystem. Yet, throughout maritime history, humans have also unwittingly provided some of the most popular island habitats in the sea: shipwrecks. Though not all of these vessels are suitable for ocean communities, many have become refuges for countless marine species (some native, some not) that prefer the safety of wooden beams or steel hulls to sandy bottoms and rocky outcrops.

Here are five examples of ocean life that rely on shipwrecks as their home.

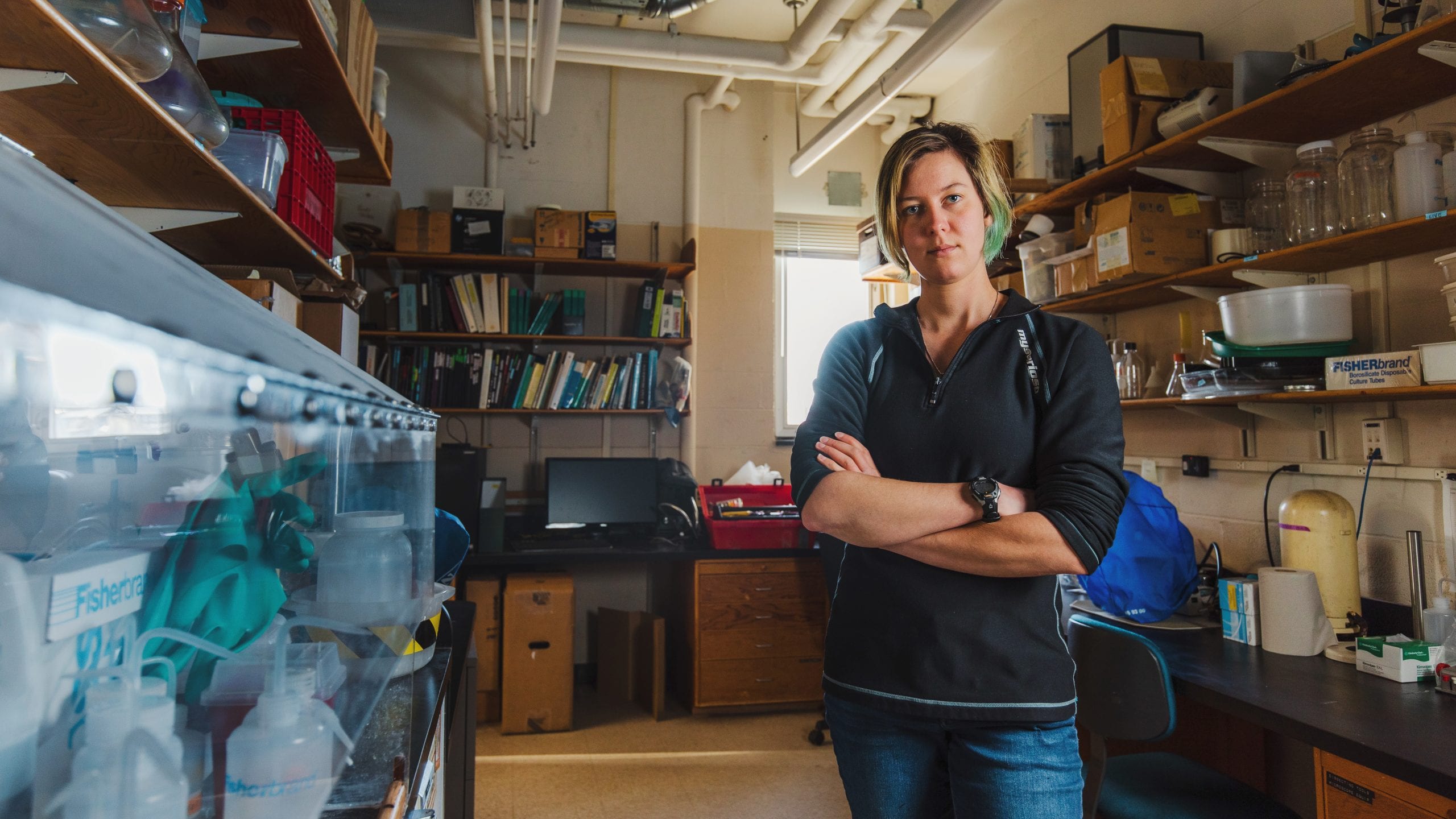

Fluffy Anemone (Metridium senile)

A fluffy anemone (Metridium senile), grows on the shipwreck of F/V Patriot in Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. (Photo courtesy of Kirstin Meyer-Kaiser via unnamed diver)

Fluffy anemones are common residents on most shipwrecks in the North Atlantic and are easily identified by their feathery tendrils and ghostly colors. As filter feeders, they often grow from high vantage points to skim nearby currents for tasty particles and swarming zooplankton. In Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, New England, WHOI biologists have recorded more-concentrated populations of these animals along shipwrecks than on other native substrates like boulder reefs. If you’re lucky enough to scuba dive on an Atlantic shipwreck, keep a weather eye along overhangs and tall beams like the crow’s nest or the bow pulpit for these dainty invertebrates. You’ll likely spot more than one if you do.

Sun Coral (Tubastrea coccinea)

A colony of sun coral propagates along the hull of an unidentified fishing or survey vessel in the Gulf of Mexico. (Photo by Evan Kovacs, © Marine Imaging Technologies)

Another species that likes to “hang out” is the sun coral. This vibrant soft coral species is easily distinguished by its larger polyps and its pastel yellow-orange colors (sometimes with hints of magenta). Not native to the Gulf of Mexico, this species began to appear prolifically in the last century, carving out territory in shipwrecks to compete with native barrier reef species. Unlike most corals, sun coral does not have symbiotic bacteria in its tissue to help it make food. Instead, it relies on its tentacles (much like anemones) to catch passing prey.

Regal Demoiselle (Neopomacentrus cyanomos)

The regal demoiselle is native to the Indo-Pacific and invasive along shipwrecks across the Caribbean. (Photo by Adobe Stock)

Just as corals take up residence on wrecks, so too do the fish that interact with them. The regal demoiselle is a common species of damselfish that keeps close to wreck-bound corals, such as the delicate ivory bush coral (Oculina tenella). It can be identified by its charcoal-gray body and bright yellow tail tips. Non-native to the Caribbean, it was likely introduced from the Indo-Pacific along with infrastructure for oil drilling. Its presence is an example of how shipwrecks can support complex marine communities over time.

Lobe Coral (Porites lobata)

A colony of Porites lobata grows on a shipwreck in Palau. (Photo by Kirstin Meyer-Kaiser, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The waters around the island nations of Palau and Chuuk are a favored tourist destination for World War II–era shipwrecks and planes, many of which are now coated with termite-like mounds of Porites lobata, or lobe coral. As with most boulder species, this coral has a rocky exterior, dark colors, and thousands of tinier polyps that mushroom upward. The species can be found growing on the topmost surfaces of shipwrecks, where it’s thought that it is more likely to capture sunlight from the surface waters. Why lobe corals prefer the substrate of a shipwreck to other habitats is the subject of ongoing research by WHOI’s Meyer-Kaiser Lab.

Atlantic Goliath Grouper (Epinephelus itajara)

A goliath grouper glides over an unnamed shipwreck. (Photo by Adobe Stock)

It’s not uncommon for scuba divers to get hip-checked by a massive grouper while diving along a shipwreck. The Atlantic goliath grouper earns its name from its enormous size and weighty frame. This fish is notorious for lumbering around shipwrecks, ambushing nearby prey, and taking respite inside dark hulls and under overhangs. They can grow up to 8 feet long and weigh a whopping 800 pounds! Unfortunately, Atlantic goliath groupers have also been the target of overfishing, leading to a nearly 80% dip in population numbers, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Current data suggests that a disproportionate number of remaining goliath groupers have found sanctuary in only a handful of shipwrecks across the Caribbean.