2009 Research Highlights

Eleanor Bors

Exploring deep-sea lifeWhile her Oberlin classmates were accepting their diplomas at their graduation ceremony back in Ohio, Eleanor Bors found herself on board the research vessel Kilo Moanaalmost 200 miles off the coast of Guam. It was an opportunity too good to pass up.

The voyage marked the first field deployment of Nereus, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s (WHOI) new hybrid remotely operated vehicle, capable of diving far deeper than any other current vehicle. Its target was the Challenger Deep in the western Pacific Ocean—at about 11,000 meters or 6.8 miles below the surface, the deepest recorded point in the ocean.

Nereus provided an exciting opportunity to investigate previously unexplored territory for WHOI scientists—including Bors’ advisor, biologist Timothy Shank.

“Deep-sea biology is what I’ve been drawn to most—it’s kind of a frontier of marine science,” said Bors, who earned degrees in biology and cello performance from Oberlin. “Some of the species we observed may never have been collected before,” including sponges and stalked anemones.

Back in Woods Hole, Bors worked on genetic methods for identifying larvae as part of a study of how worm communities recolonize hydrothermal vent sites after volcanic eruptions. Organisms like these have evolved specialized mechanisms to survive in such extreme conditions. Bors continued work on this project into the fall.

A Seattle native, Bors has always loved being near the ocean, which steered her toward marine science. While this summer marked Bors’ first research cruise, she had plenty of opportunities to find her sea legs while earning her sailing certification on 25-foot keelboats and traveling the Atlantic on the Sea Education Association’s Corwith Cramer in high school.

In addition to deep-sea biology, Bors has a keen interest in environmental policy and its relationship to science; she is considering a future in one or both fields. This was one of the many subjects Bors discussed in her summer blog, In an Octopus’s Garden, which provides an insider’s account of life as a Summer Student Fellow.

Outside the lab, she enjoyed “nerding out” and exploring Cape Cod with her peer fellows and sailing in knockabout races in the waters off Woods Hole.

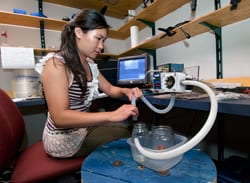

Stephanie Chin

A biological sampler for underwater vehiclesStephanie Chin is most likely the only Summer Student Fellow whose project could one day operate in space—at least in theory. She worked on building a prototype for a biologic pump sampler for the autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry, under the guidance of scientists Rich Camilli, Chip Breier, and Dana Yoerger in Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's Deep Submergence Laboratory.

Sentry is designed to discover deep-sea hydrothermal vents, but NASA has partly funded the project with the hope that the technology might be applicable to space exploration, particularly on Jupiter’s massive moon Europa, which may have an ocean beneath its icy surface. Sentry is a free-swimming robot that can explore without any attachments to a larger ship, which enables it to travel to remote locations. Autonomous vehicles currently require programming before they start exploring, but the goal is for Sentry to make its own navigation decisions based on what it senses along the way—a technology WHOI scientists are constantly working to refine.

Marine biologists often use pump samplers under water to look at organisms filtered through large amounts of seawater, but the the samplers are traditionally attached to a tethered remotely operated vehicle (ROV) or to fixed moorings. By creating a pump sampler for an AUV such as Sentry, Chin and her advisors hope to expand the possibilities of underwater biology exploration.

“By designing a compact unit to put on an AUV, scientists can gain the freedom of not needing to have a priori knowledge of the terrain,” Chin said. “Samples can still be taken along the AUV track, and in communication with onboard sensors, the AUV could be used to ‘sniff out’ interesting places to take samples.”

The sampler, which can filter larvae, plankton, and microbes, could also collect samples of DNA from marine life. Some of its components include an advancing filter on a spool that can store samples, and a fluid motion pump with a flexible impeller, which turns itself with changes in pressure and provides a uniform flow. All that must fit into a compact package that doesn’t take up valuable space on Sentry. Chin built and tested a prototype of the sampler herself.

“You get a lot of skills having your own project, learning to manage everything yourself,” she said, although she credits her Deep Submergence Lab colleagues with helping her improve the design along the way.

Chin is a senior with a major in mechanical and ocean engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she participates on the ROV team. The Westwood, Mass., native also enjoys reading and dancing and expects to go to graduate school to continue studying ocean engineering.

Willy Goldsmith

Basking shark migration

Willy Goldsmith is a fish guy. At home in Boston and Gloucester, Mass., he is an avid lifelong fisherman. He also works in the ichthyology collections at Harvard University, where he is a senior majoring in history and minoring in organismic and evolutionary biology. He has written about his fishing experiences since he was 16, for magazines such as The Fisherman, On The Water, and Salt Water Sportsman. His avocation became a serious scholarly pursuit at WHOI this summer, where Goldsmith studied basking shark migrations in Simon Thorrold’s fish ecology lab.

“I’ve always liked fisheries research and working at the ichthyology collection, and working in Dr. Thorrold’s lab was a chance to make that interest an academic focus,” Goldsmith said.

Basking sharks—the world’s second-largest fish—are a pelagic species whose habits have long eluded scientists. A recent study of basking sharks tagged off Cape Cod by biologist Greg Skomal of the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries revealed for the first time that they can undertake trans-equatorial migrations through tropical waters, traveling at depths of 200 to 1,000 meters to avoid warm surface temperatures. This finding indicates that the world’s basking shark populations, thought to be restricted to temperate oceans, may in fact interbreed.

To discover more about the species’ migration patterns, Goldsmith studied raw data recorded by a tag from a 20-foot female basking shark that died and washed up in Newport, R.I. During its deployment from June to September 2005, the tag recorded light levels, water temperatures, and depths every 30 seconds as the shark swam. Goldsmith used the data to reconstruct the shark’s diving patterns as well as to refine methods for locating a shark’s geographical position from tag data. Goldsmith hopes that knowledge of this individual shark’s diving behavior and migratory pathway can lead to new conservation efforts to protect the vulnerable species.

Beyond research and fishing, Goldsmith managed to find time to play on two local softball teams, sail, bike, and learn how to cook—local fish, of course—alongside his housemates at the Barn. Remarkably, while on a fishing trip in Cape Cod Bay this summer, Goldsmith encountered one of his study subjects.

“A 20-foot (basking) shark came right up to us and collided with our boat,” he recalled.

Goldsmith is considering working in fisheries management, as well as studying biology, after graduation.

Tara Hetz

Maine lobsters and right whalesTara Hetz has gotten to see a different side of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) from her Summer Student Fellow (SSF) peers this summer as the sole fellow at the Marine Policy Center. With WHOI research specialist Hauke Kite-Powell, she analyzed risks posed by fishing gear to endangered North Atlantic right whales.

Hetz, a senior conservation biology major from St. Lawrence University, hails from Charlotte, Vt. Her project involved treading the tricky line between science, law, and the fishing industry—in this case the Maine lobster fishery. Right whales often become entangled in the lines that connect lobster traps on the seafloor to buoys on the sea surface. The lines can get wrapped around the whales and cut into their skin, leading to slow, painful death.

The Maine coastline consists of several distinct fishing zones, all with different regulations. Hetz’s job was to work with fishermen and policymakers to develop a tool that will allow lobstermen to sustain their livelihoods while protecting the whales. She developed a model that asks: At a particular time of year, in one area of the water, what is the specific level of risk of a whale traveling there? The model would allow fishermen to distribute their traps in places and at times when whales are not likely to be in a specific area.

“The model will go to the fishermen, management people, and whale biologists, and then they can collaborate to control the fishing effort without a policy-based series of strict government regulation,” which often hinders fishermen, Hetz said. The model can evolve over time as right whale research improves or fishing regulations change.

To get a better sense of the situation in the fishery, Hetz traveled to northern Maine, where she met with fishermen in Cutler and Sprucehead to learn about their fishing methods. She also attended a Lobstermen's Association Meeting and showed fishermen her project. But more important, she wanted to understand the fishermen’s perspective on the issue of right whale entanglement.

“I learned about the hardships they’re dealing with, because this is how they put bread on the table,” said Hetz. “You see the dead whales and feel that you have to protect them, but also understand that the fishermen need to live, too.”

Aside from her project, Hetz had plenty of fun outdoors in Woods Hole with the other SSFs, “playing basketball, Frisbee, going swimming, and running," she said. "It’s like summer camp for science nerds.”

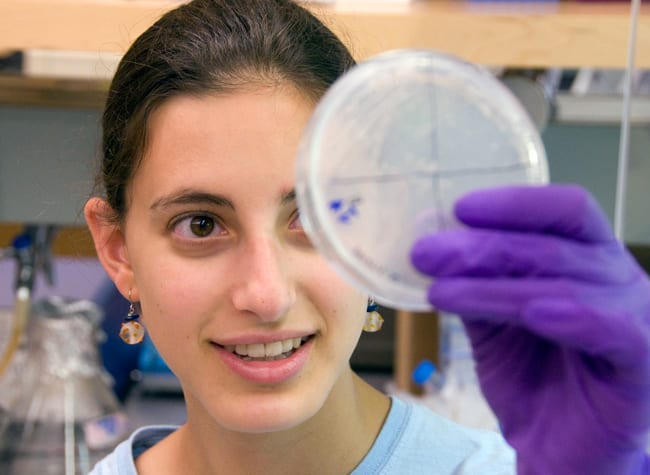

Rose Kantor

Quorum sensing among bacteria“Being from the Midwest,” said Minneapolis native Rose Kantor, “it had never even crossed my radar to do oceanography.” The biology major from Carleton College applied to a dozen institutions for summer research fellowships and was surprised to find that her ideal microbiology project would not only bring her to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) but also to the fjords of Vancouver Island, Canada.

She started her Summer Student Fellowship with WHOI marine chemist Tracy Mincer on a cruise to Clayoquot Sound on board the research vessel Clifford A. Barnes to study bacterial communication and the carbon cycle. The cruise involved five days of collecting samples of marine particles in sediment traps and bringing them back to Woods Hole to culture in the lab. Mincer and Kantor wanted to gain a better understanding of how bacteria communicate via chemical signaling called quorum sensing.

Quorum-sensing bacteria produce and release chemical signal molecules that become more concentrated as more bacteria aggregate in an area. Kantor was responsible for isolating pure cultures of bacteria, freezing them, and sequencing their DNA. That enabled her to identify each culture and study how they regulate the expression of the genes encoding the enzymes that produce the chemicals the bacteria use to communicate.

“The interdisciplinary nature of my project kept it interesting throughout,” Kantor said. “My favorite parts were the cruise in Clayoquot Sound and the day I got my DNA sequences back and was finally able to identify some of the bacteria I'd been culturing.”

“This program has given me a feel of how research is done in oceanography, from the cruise to the lab to the Ph.D. defense, “ said Kantor. “It gave me opportunities to learn about subjects I never would have heard of at my home college.”

Kantor wants to pursue a career in science at some point in the future but hopes to take a few years to decide exactly what she wants to study. After graduating next spring, she is considering returning to South America as a volunteer (she speaks Spanish and spent a semester in Ecuador). She also enjoys singing, swimming, and poetry.

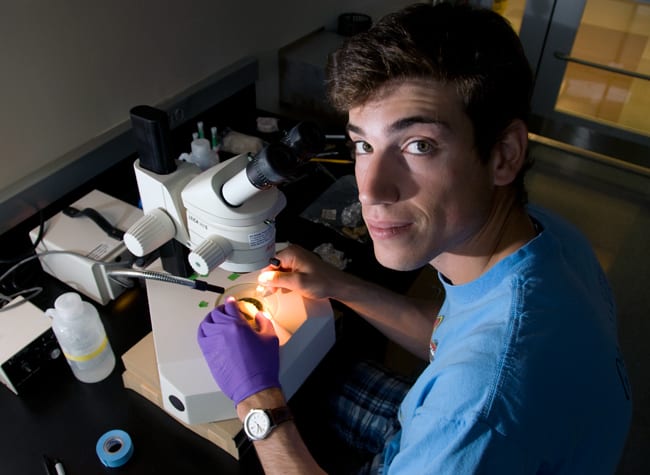

Abigail Labella

Fish, genes, and pollutantsAbigail Labella sums up her daily life as a biology Summer Student Fellow (SSF) in a single maxim: “When the fish call, you can’t really say no!”

Whereas many of us struggle to remember to feed a single pet goldfish, Labella enjoyed the responsibility of looking after an entire laboratory’s worth of fish. “I plan my life around fish feeding and fish collections,” she said.

Labella spent her summer in biologist Ann Tarrant’s lab at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), studying genes that regulate endocrine hormone pathways in fish that were exposed to chemicals such as bisphenol A (BPA), a potentially hazardous compound found in many plastics, and diethylstilbestrol (DES), a synthetic estrogen.

In the lab, Labella measured how genes are expressed, or activated to produce proteins, in killifish exposed to BPA and in zebrafish embryos exposed to DES. She also traveled to Scorton Creek in Sandwich, Mass., and New Bedford Harbor, Mass., to collect the fish samples.

The independence afforded SSFs at WHOI has been Labella’s favorite aspect of her project, as well as the opportunity to learn new techniques. “We’ve been injecting embryos with a microscopic needle to knock down genes, which is a tool that I can use a lot,” Labella said.

She also had high esteem for her SSF colleagues, whom she described as “impressive” and “really willing to share what they’re doing” in their own projects, as well as for her lab mates. “Lab work can be really fun when everyone has a positive outlook and a sense of humor,” she said.

A biology major and physics minor, Labella is a senior at American University and a native of Ballston Spa, N.Y. She is also a devoted Ultimate Frisbee player, both at American and in Woods Hole.

Her experience as an SSF has solidified Labella’s ambition to continue studying marine genetics in graduate school. Genetics is an interest Labella acquired in college, but she has wanted to be a marine scientist since childhood. After shadowing a marine biologist in sixth grade, Labella knew that WHOI was the perfect place to pursue this interest.

“I’d always wanted to come here and find out what it’s like,” she said, “and I’ve realized that I really do enjoy working here.”

Cara Manning

Tracking the greenhouse gas N2OOne of Cara Manning’s hobbies is cooking, which seems compatible for a chemist, right?

“Some of my nonscientist friends are convinced that my culinary skills are related to my chemistry background because cooking involves measuring things accurately and following directions,” she said. But in the kitchen, Manning likes to modify recipes, changing and adding ingredients in a way she’d never try in the lab.

This summer, Manning worked on Oyster Pond, a Cape Cod kettle pond with a high surrounding population density that is probably changing the pond’s chemistry. Manning investigated how much nitrous oxide is entering the pond from sources other than the atmosphere, how much is being generated by microbial metabolic processes in the pond, and how much is released into the atmosphere. The questions are important because nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas.

From an inflatable boat, Manning collected water samples and incubated bacteria in the samples with different nutrients to see whether they produced more or less nitrous oxide. The boat was borrowed from a “scientist down the hall from our lab who purchased it for his research and said we could use it,” she said.

Manning, a senior chemistry and earth and ocean sciences major at the University of Victoria in Canada, has set her sights on a graduate degree in chemical oceanography. Part of the draw of the WHOI Summer Student Fellowship program for Manning was that WHOI is among the few U.S. institutions that welcomes international students for such undergraduate internships.

The 3,000-mile leap—her second time on an airplane—meant the opportunity to explore new surroundings, whether on a bike around Woods Hole or on trips to Boston and New York, and even on Oyster Pond at midnight, collecting samples with a headlamp. It also expand her horizons as a chemist.

“I’ve been exposed to new techniques and a whole range of oceanography that isn’t taking place at home,” Manning said. “There are only two chemical oceanographers at my university.

“My favorite experience was presenting at the marine chemistry departmental seminar,” she said. “I felt honored to present in front of scientists that I consider role models.”

Garrett Mitchell

For Garrett Mitchell, an interest in oceanography arose not in a university classroom but on a surfboard in the waters of California. Living there while taking a few years off from school, he became an avid surfer and diver and decided to turn a hobby into an academic pursuit.

At the University of Maryland, College Park, Mitchell earned degrees in geology and geography and spent time studying ocean mapping, particularly of mid-ocean ridges. In the fall, he returned there to study for his master’s degree in geology.

This summer, he worked in the lab of marine volcanologist Adam Soule, developing a photomosaic of images from the southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the site of a recent undersea volcanic eruption. In 2006, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's autonomous underwater vehicle called ABE collected hundreds of images from around an unexplored region of the mid-ocean ridge. The hope was to use the physical appearance of the seafloor, rather than its bathymetry (or depth), to create a new way to study how lava flows create features on the seafloor.

Mitchell’s job was to organize and color the images collected by ABE according to the lava flow structures he observed in each photo. He prepared the images to be sent to the University of Girona in Spain, where a unique kind of software could refine the images and create a workable map of the eruption zone. He also studied how the lava flows affected how and when hydrothermal vents in the area were distributed.

“The photomosaic of images is a new tool for studying mid-ocean ridge processes,” he said. “It’s still a frontier science, so there are a lot of questions we’re going to have to answer.”

Mitchell hopes to pursue similar ocean-mapping projects in his future career, which includes plans to study for a Ph.D. in oceanography. He is especially interested in using mapping to study seafloor morphology and dynamics at the boundaries of Earth’s tectonic plates, and believes that similar techniques could be used to study marine geohazards affecting the offshore oil and gas industries.

Mitchell said his experience as an Summer Student Fellow has helped him to learn more about his chosen field. “I was reading a book the other day,” he said, “and the author just walked into my office with my advisor.”

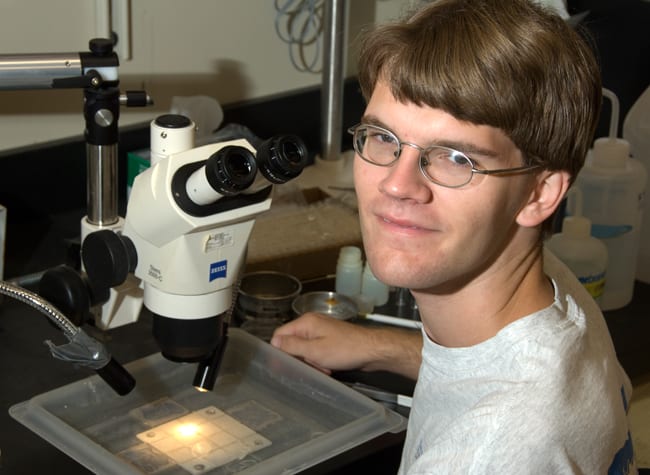

Gar Secrist

Life at hydrothermal ventsGar Secrist says that he spent his summer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) working on “sandwiches.” His weren't ordered in from a deli, but rather retrieved from the seafloor. One look at the tubeworm-encrusted plastic devices he studied—called “sandwiches” and used to collect organisms from seafloor hydrothermal vents—would distract even the most determined of appetites.

Secrist, an ecological biologist, worked with WHOI biologist Lauren Mullineaux, who was a Summer Student Fellow herself as an undergraduate. Her laboratory collected more than 30 sandwiches from P-Vent on the East Pacific Rise mid-ocean ridge. Secrist’s task was to study and count the variety of creatures on the sandwiches through a microscope.

With this data, scientists hope to gain a better understanding about how animal populations recolonize hydrothermal vents after seafloor communities are wiped out by volcanic eruptions. Secrist also compared data on the temperatures and sulfide levels in fluids spewing from the vents to see whether certain organisms may prefer certain vent chemistries.

Before this summer, Secrist had been to sea with WHOI’s neighbor, Sea Education Association, which introduced him to oceanography and marine ecology. Secrist credits this summer’s work with granting him a new enthusiasm for marine science and the new frontiers being explored in oceanography at WHOI.

“I’m seriously considering a future in marine biology now,” said Secrist. “With this project I’ve had more independence than in other labs. I’ve been able to look at data and figure out for myself what I’m interested in studying, which has been beneficial.”

Secrist graduated in May with a biology degree from Maryville College, located near his home of Knoxville, Tenn. He plans to spend this fall working at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center's Marine Invasions Research Lab in California before applying to graduate schools in biology. He plays the cello and is learning the piano, enjoys hiking and camping, and exploring the Woods Hole area and other parts of the Northeast.

Clara Smart

Ask Clara Smart about her interests, and be prepared to receive a formidable list of hobbies and academic pursuits: photography, competitive cycling, knitting, English literature, the ocean, jazz, and robotics.

Smart is an electrical engineer about to enter her final year in Northwestern University’s five-year Walter P. Murphy Cooperative Engineering Education Program. As part of her co-op, she has worked for defense company Northrop Grumman and participated in several university projects on which she honed her skills as an electrical-mechanical systems and control systems engineer. “Basically, that means robots,” she said.

Since watching a film about underwater robotics in seventh grade, Smart aspired to work in the Deep Submergence Lab at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and help build devices for marine research. She reached her goal this summer working with WHOI scientist Hanumant Singh. She combined her interests in engineering and the ocean with her love of photography by working on undersea image processing.

Smart, a native of Seattle, spent the summer devising a new kind of faceted reflector light for use on deep-sea exploration vehicles, from the mathematical modeling of the device to the construction. The goal is to create a more even light field for taking underwater pictures. By replacing light originating from a single point, such as a bulb, with a mirrored reflector, engineers could eliminate false shadows and achieve clearer, more accurate images under water.

Smart’s SSF experience also included testing some deep submergence vehicles and observing some of the other scientists’ projects.

“I’ve definitely come to consider a future in image processing much more, as opposed to the very heavily mechanical side of things,” said Smart, who is considering a graduate degree in applied ocean physics and engineering. “What I really want to do is work with robotics and sensors for marine research, and this place is the mother ship.”

She also enjoyed at WHOI life outside the lab, exploring the Cape and long-distance cycling.

Sam Zipper

Climate change and the Arctic permafrostIt might seem strange that Sam Zipper spent his summer on balmy Cape Cod studying the western Canadian Arctic. But for Zipper, examining sediment cores from the Mackenzie River Delta with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) geologist Liviu Giosan was a great way to connect his interests in geology and environmental analysis. He studied both at Pomona College, where he graduated last spring.

In the Coastal Systems lab at WHOI, Zipper analyzed the cores to construct a record of how sediments within the watershed changed over the past 1,000 years and examined how the permafrost responds to climate change.

The river delta contains thousands of small lakes, which annually flood with sediment-laden water during the spring snowmelt. This provides distinctive layers of sediment, which are ideal for assessing yearly fluctuations of carbon levels, sediment particle sizes, and other geological and geochemical clues. Those clues will reveal how the composition of the permafrost changed during and after ancient periods when Earth’s climate oscillated naturally into what are known as the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age.

“This will hopefully let us know how much carbon we can expect to enter the atmosphere in the future due to permafrost degradation,” Zipper said. Melting permafrost is one of many results of warming climate in the Arctic and also leads to ecosystem changes and land subsidence. “This is a kind of pioneer study, and will give us some background about the hydrology of the Arctic.”

Zipper said he plans to pursue some kind of career in the earth sciences. “I’m interested in the interactions of earth, water, and people, but I’m not really sure where on the spectrum.”

Before returning home to Edmonds, Wash., Zipper planned to hike the White Mountains section of the Appalachian Trail. He will return to the Coastal Systems Group in the winter to work as a research assistant.