Moored Profiler

What is a moored profiler and why do we use it?

A moored profiler makes repeated measurements of ocean currents and water properties up and down through almost the entire water column, even in very deep water. The basic instruments it carries are a CTD for temperature and salinity and an ACM (acousting current meter) to measure currents, but other instruments can be added, including bio-optical and chemical sensors.

As interest in global climate change grows, so does our need for long records of ocean variability. Data collected over seasons and years are critical for developing ocean-atmosphere models, and learning about air-sea interactions. Moored profilers were conceived as a cost-effective way to conduct long-term ocean sampling.

How does a moored profiler work?

The moored profiler is attached to a subsurface mooring cable that can run from a depth of 50 meters (165 feet) down to the sea floor at 5,000 meters (3 miles) or more. The profiler uses a battery-powered traction motor to climb up and down the mooring. Its sensors document water and current properties as the profiler climbs or descends.

The profiler has enough battery power to travel a total of about one million meters per deployment. (Deployments often last a year at a time.) An onboard microprocessor can be programmed to conduct complex sampling schedules. These include burst sampling, in which several profiles are collected in a day followed by several days of no sampling, with the whole pattern repeated through the deployment. Burst sampling minimizes "alias errors," where unresolved high-frequency motions contaminate long-period signals.

The moored profiler stores its data for the duration of its deployment. Scientists download the data when they recover the instrument. Engineers and designers are looking ahead to the prospect of sending data home in real-time via satellite. (At present moored profilers can't contact satellites because radio communication doesn't work through sea water.)

How was the moored profiler developed?

Research groups and companies from several countries have developed moored profilers. At WHOI, members of the Advanced Engineering Laboratory of the Department of Applied Ocean Physics and Engineering working with members of the Department of Physical Oceanography to develop the WHOI moored profiler.

This work began with grants from the National Science Foundation and the WHOI Director's Discretionary Fund. Follow-on support was obtained from the Office of Naval Research and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In 1998, WHOI's licensed its moored profiler technology to McLane Research Laboratories, Inc. of nearby Falmouth, Mass., who are now marketing an improved profiler (called the McLane Moored Profiler, or MMP).

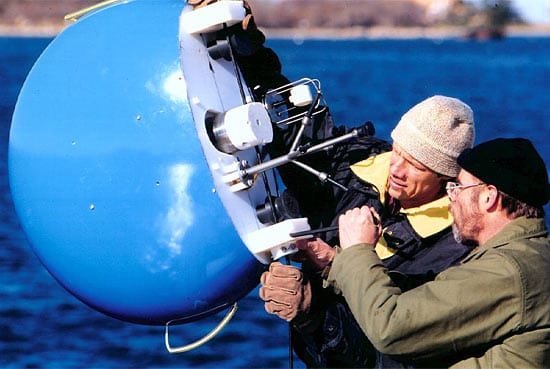

The main difference between WHOI's instrument design and the MMP is the pressure vessel for the main electronics and battery. The WHOI prototypes placed these systems inside glass spheres; the MMP uses a titanium pressure case, which is easier to service. To accommodate the new pressure case, McLane developed a new mechanical layout and gave the MMP a streamlined cylindrical shape.

Advantages

Moored profilers record water conditions over immense depths - up to 5,000 meters (3 miles). A single CTD cast to that depth from a ship would take many hours.

Moored profilers operate for up to a year at a time, so they record daily and seasonal changes that would be simply impossible to collect from a ship.

Limitations

Moored profilers climb up and down subsurface mooring cables, which usually are festooned with instruments measuring many aspects of the water. The profilers need a clear run of cable, so scientists can't place instruments in a profiler's path. To get around this problem, subsurface moorings are often set out in pairs, with a moored profiler on one and and other instruments on the sister mooring.

As with most subsurface instruments, moored profilers are limited by being isolated from the surface. They have to carry their own batteries to power instruments and the motor, and the life of the batteries limits how long the profiler can stay out. Also, the profiler never comes to the sea surface, so it's cut off from radio contact with satellites. Researchers have to wait until the deployment is over to see their data.