CLIMATE & WEATHER

How will we ever count them all?

Ocean Life

How will we ever count them all?

That is the question on all our minds when, at 1 a.m., the peak of high tide, hundreds of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) arrive, dragging themselves along the beach, driven by the primal urge to dig a nest and lay their eggs. They are everywhere, in numbers almost unimaginable only a few years prior. Every female carries a hundred eggs or more, each egg the size of a ping pong ball. I make a quick calculation, just long enough to feel dizzy at the thought of how many of these delicate, life-filled shells are already beneath my feet. 2020 is a record-breaking year for the green turtles of Poilão, the southernmost island of the Bijagós archipelago in Guinea-Bissau. In more than 30 years of monitoring, researchers from the Instituto da Biodiversidade e das Áreas Protegidas ("IBAP," the government institute for biodiversity management and conservation) have never seen anything like it.

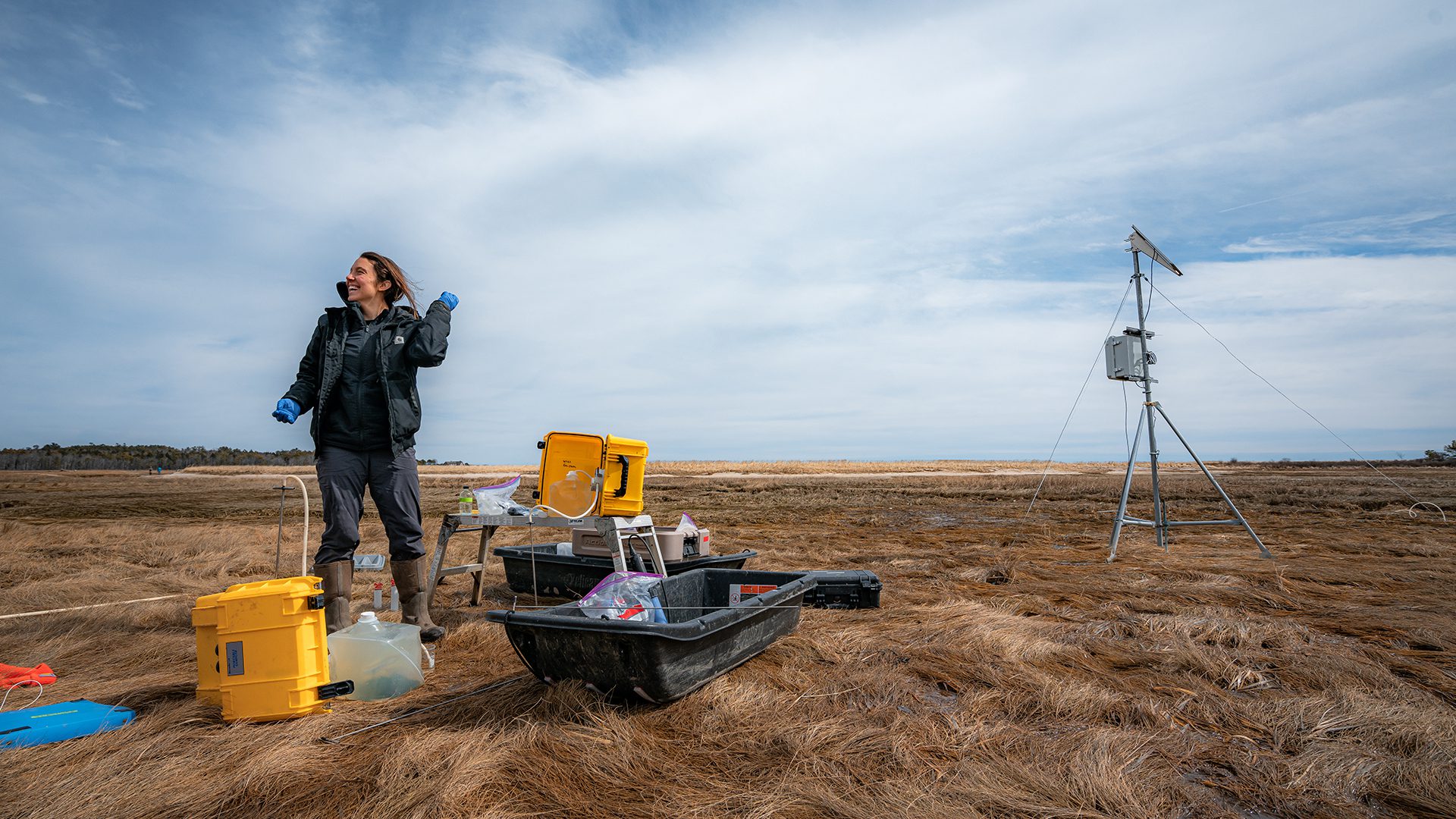

WHOI ecologist Francesco Ventura. (Photo by Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

We arrive on the island of Poilão after a 10-hour journey from the port of the capital, Bissau. The small, uninhabited island is the most important nesting site for green turtles in Africa. This corner of the world is not only a sanctuary for green turtles but also a hotspot for human diversity. Guinea-Bissau is home to numerous tribes who have inhabited the region for centuries, each developing different customs, traditions, and languages. For the Bijagós people, who live on the mosaic of 88 islands composing the archipelago, Poilão is sacred and can only be visited after passing several trials and a rite of passage.

Upon our arrival, we are welcomed by a small team of local technicians and biologists. Together, we gather in front of a small totem at the edge of the forest to perform the sacred ritual. One by one, we express our gratitude to Musueda, the spirit of the island, for granting us access and allowing us to study the turtles up close. The tall baobab and kapok trees form an impenetrable boundary around the forest, creating a palpable sense of magic and pristine beauty.

Poilão is a true success story for both the conservation of green turtles and the positive impacts the program has in local communities. IBAP is in charge of the monitoring program, employing full-time park wardens of Bijagós ethnicity, training and hiring local young people to raise environmental awareness and support their education. Paulo Catry — my former Ph.D. advisor — and Rita Patricio of the Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre in Lisbon, Portugal, established the long-term monitoring program in synergy with IBAP.

According to Catry and Patricio, the sacred status that the island of Poilão holds for the locals has certainly contributed to the preservation of the turtles' nesting site, but that alone was likely not enough. Until recent years, turtles were illegally killed and accidentally caught by artisanal fisheries. With the full involvement of local communities, the turtle monitoring program was instrumental in the delineation of the João Vieira and Poilão Marine National Park in 2000, now recognized as one of the most important turtle nesting sites in the world. Here, the protection of turtles goes hand in hand with improved living conditions for local residents through access to education programs and new job opportunities as conservationists for the park.

As I stand awestruck on a dune overlooking the moonlit shore, I'm abruptly reminded of what I'm supposed to be doing as a mouthful of sand hits me right in the face, flicked by the powerful flippers of a female busily digging her nest. For the next four hours or so, our team patrols the beach of Poilão, counting the number of nesting females and deploying satellite trackers to identify the population's foraging grounds and migratory routes. The island is bursting at the seams with life, and the sand boils with turtle hatchlings synchronously emerging and taking to the sea for the first time.

As our turtle-counting shift draws to a close, we sit on the beach, tired but happy. I am forced to move aside by a female who, with reptilian nonchalance, starts digging at my feet. Observing the rhythmic, almost robotic, movements of her back flippers, I think to myself: "What a way to live life!" Sea turtles have been doing this successfully for about 120 million years. The temporal perspective makes me feel small, like a grain of sand on the beach of the island — and, just like a grain of sand, a tiny part of something infinitely larger.

Without saying a word, I look at my colleagues and friends, sharing in this moment of absolute communion with nature, the silence interrupted only by the deep breathing of the giant turtles surrounding us. I cannot help feeling grateful. The world is a wonderful place.