Beach Closures

You never want to see a sign like this on the beach. The waters off beaches are regularly tested to ensure that they don’t contain unhealthful bacteria levels. But a lag time between when the water is sampled and when the results come in can cause beach closures after bacteria have dispersed, or openings when bacteria are present but not yet counted. New methods of detection based on identifying bacterial DNA can significantly shorten the time between sampling and results and let managers make more timely decisions about beach closures. (Photo by Elizabeth Halliday, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

What Causes Beach Closures?

The pollution that causes beach closures and illness in humans comes from many different places on land, but ultimately gets into the water primarily through one of two pathways—discrete point sources and diffuse non-point sources.

Point sources are single, identifiable inputs of polluted water that can often be monitored or controlled because they are readily identifiable. These generally include pipes or culverts pouring pollution directly into the water from a home or business. Non-point sources are diffuse flows passing over or through land (which might contain the pollution) before entering a water body. These are more difficult to detect, monitor, and control because they tend to be more variable, are often spread out over wide areas, and often invisible.

Many of the most common pollutants come from one of two places: humans and animals. Human fecal matter in water bodies constitutes the greatest public health threat because humans are reservoirs for many bacteria, parasites, and viruses that are dangerous to other humans and can cause a variety of illnesses. Residential buildings are a primary source of many of these pathogens, and the cause of many problems can often be traced back sewage overflows or leaky residential septic systems.

Runoff from agricultural land is also a serious health concern. Animal fecal waste may contain pathogens such as Cryptosporidium, or Salmonella. Likewise, pet waste can pose health threats to humans. A single dog feces contains more than 40 million enterocci bacteria (an indicator of other, more serious pathogens) and is equivalent to nearly 7,000 bird droppings.

Water running off of nearby land is often a major source of problems and pollution that closes urban beaches. Even a moderate rain can send enough water storm drains to overwhelm older “combined sewer systems” that mix runoff and sewerage. When a rainfall adds enough extra water to the system that the treatment plant cannot process everything fast enough and the excess, untreated water to flows into a nearby river, lake, or coastal area. That is why many beach closures occur after rainstorms—and why many municipalities now close beaches in advance of heavy rain.

Runoff from fields, lawns, parking lots, and streets can also wash directly into nearby waterways when it rains, carrying with it any pollutants that might have been on land. Even watering a lawn or washing a car can carry potentially harmful pathogens into the water. Leaky or malfunctioning septic systems, too, can cause potentially harmful pollution to seep slowly through the ground and into nearby lakes, rivers, and streams.

Why are Beach Closures Important?

In addition to disrupting a day at the beach, water pollution poses a serious health threat to beachgoers. The most common illness arising from contact with polluted beach water is gastroenteritis, an inflammation of the stomach and the intestines that can result in vomiting, diarrhea, cramps, and fever. Other minor illnesses include rashes and infections of the ear, eye, nose, and throat.

People can contract some illnesses simply by getting polluted water on their skin or in their eyes and nose. In a few cases, swimmers develop infections when an open wound is exposed to polluted water. These usually require little or no treatment and have no long-term health effects, but should be treated as soon as they arise. In very polluted water, however, swimmers can be exposed to more serious diseases like dysentery, hepatitis A, cholera, and typhoid fever.

Those with frequent exposure to water (such as surfers and divers), are most likely to get sick. Children, the elderly, people with weakened immune systems are most at risk of severe illness or of suffering complications from a wide range of illnesses contracted by exposure to water by any of a number of pathogens.

What Makes You Sick?

The infectious organisms found at the beach include bacteria, parasites, and viruses. The most common ones come from the stools of people or animals.

Salmonella are a group of bacteria that pass from the feces of infected people or animals to other people or other animals and can cause diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and vomiting between eight and 72 hours after exposure. Salmonellosis, the infection caused by consuming food or water containing Salmonella, results in an estimated 1.4 million cases and more than 400 deaths annually in the U.S.

Shigella are a group of bacteria that pass from the feces of an infected individual to other people and can cause diarrhea (often bloody), fever, and vomiting about a day after exposure. Approximately 14,000 cases of shigellosis, the infection caused by Shigella, are reported in the U.S. annually, though many more likely go unreported, as symptoms often resolve after a few days.

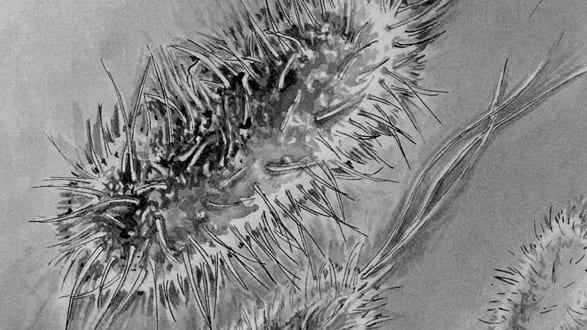

Cryptosporidium is a microscopic parasite that can live in the intestine of humans and animals and is passed via feces to another person or animal. Cryptosporidiosis is a disease caused by infection by the Cryptosporidium parasite and is characterized by stomach cramps or pain, nausea, vomiting, fever and diarrhea lasting an average of one week, though individuals may remain infectious after symptoms cease and may experience recurrence of symptoms. Children, elderly, and people with weakened immune systems face additional complications.

Norovirus are a group of highly contagious, related viruses that make up the most common cause of acute gastroenteritis in the U.S. Noroviruses are found in the stool and vomit of infected people, who generally recover in one to three days, but who can remain infectious for up to two weeks after symptoms cease.

Non-polio enteroviruses are second only to virus that causes the common cold as the most widespread viral agent in humans, causing roughly 10 to 15 million symptomatic infections in the U.S. each year. Most people who are infected with a non-polio enterovirus experience no symptoms; those who become ill usually develop mild upper respiratory symptoms (a "summer cold"), a flu-like illness with fever and muscle aches, or a rash.

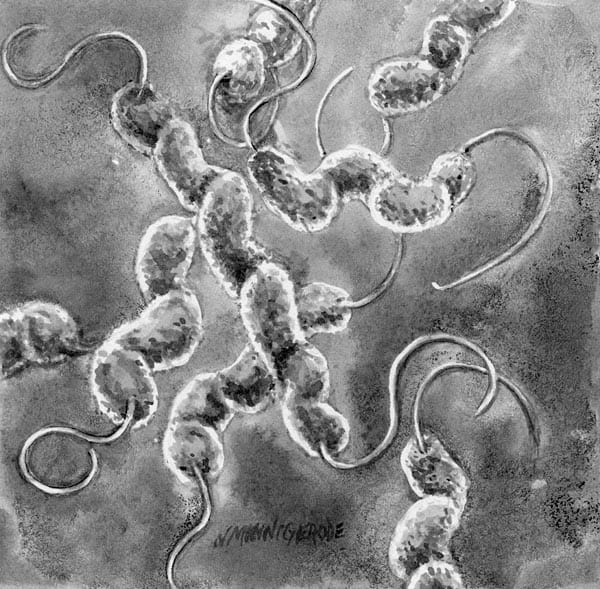

Campylobacter are another group of bacteria that infect both humans and animals and are passed via fecal material. Symptoms of infection include diarrhea, cramps and fever, and they last for about a week. About 13 cases are diagnosed each year for each 100,000 persons in the U.S., but many more cases go undiagnosed or unreported. >em>Campylobacter is estimated to affect over 2.4 million persons every year.

Giardia is a microscopic parasite that lives in the intestine of humans and animals, and spreads via fecal material. Symptoms of Giardia infections appear one to two weeks after infection are often mild in most people. The infection sometimes resolves without treatment in two to six weeks, but can include severe diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and nausea.

What You Can Do?

There are a few, basic practices you can follow to stay safe at the beach and reduce the chances that you or someone else will become sick after a trip to the beach.

At the Beach

Plan ahead. Find out if the beach you want to go to is monitored regularly and if it has had closures in the past.

Look for good swim sites. In areas that are not monitored, choose swimming sites with good water circulation and exposure to open water.

Avoid potential sources of pollution. Avoid swimming at beaches where you see discharge pipes or at urban beaches after a heavy rainfall.

Practice basic hygiene. Wash your hands before you eat after digging in the sand and wash yourself with soap and clean fresh water after you swim or wade in the water.

Clean up after your pet. Clean up after your pet, especially at the beach, but also at home, and obey pet bans at the beach.

At Home

Conserve water. Even small amounts of extra water flowing over your lawn and down residential and storm drains can send large numbers of microbes and viruses to recreational waterways and beaches.

Direct runoff to the soil, not the street. Create a rain garden or use rain barrels to direct rain gutters and downspouts to soil, grass or gravel areas rather than blacktop, cement, or other “impervious” surfaces. Sweep your driveway instead of hosing it down and increase the amount of natural, “permeable” surface wherever possible.

Maintain your septic system. Even if you live miles from the beach, have your septic tank cleaned out regularly. Such maintenance prolongs the life of the system and can help prevent groundwater and beach contamination.

Practice smart lawn and garden care. Reduce the amount of polluted runoff, by planting natural vegetation rather than lawn, which often require less fertilizer and herbicide. Do not allow water used to water your lawn and landscaping to run into nearby storm drains.

What's Being Done?

Scientists and health officials cannot easily monitor or detect all of the possible pathogens that might be in the water, and so test for what are known as “indicator organisms.” These include E.coli in fresh water and enterococcus in salt water. Both are generally not harmful, but because they are common in human and animal feces, their presence above a certain level indicates that a potential health risk exists.

On Cape Cod, the Barnstable County Department of Health and Environment monitors fresh and marine waters weekly during the summer and officials use special culture media to grow and count colonies of the indicator organisms. The EPA recommends a water quality advisory be issued when the number of indicator bacteria colonies exceeds a certain level. For E. coli, this limit 235 colony forming units (CFU) in 100 milliliters of water; for enterocci, the recommended limit is 104 CFU in 100 milliliters.

Within 24 hours of water from a particular beach failing to meet quality requirements, the Department of Health (or its authorized representative) must post signs at the entrance to the beach and each parking lot warning that the beach is closed and that swimming may cause illness. The sign must also contain the reason for the warning, the date of the posting, and the name and telephone number of the board of health. Most states also maintain websites that report the status of all monitored beaches in the state.

As soon as the agency or organization in charge of monitoring finds a problem, they will immediately resample the water. Because it takes 24 hours to culture the samples, the beach will remain closed for at least a day. The beach will be sampled every 24 hours until the indicator bacteria falls below EPA limits.

If the beach is closed, just because you stay out of the water does not mean you will be safe. High levels of indicator bacteria have been found in beach sands and one small-scale health study found an increase in gastroenteritis associated with digging in and being buried in beach sand (Heany et al, 2009). There are, however, currently no EPA standards or advisory recommendations regarding exposure to pathogens in beach sands.

Current EPA methods for detecting indicator bacteria require at least 24 hours to provide results. Because of this, a beach closure actually reflects water quality from the day before. As a result, scientists are working on ways to provide more timely water quality results.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is a method that looks for genetic material of the indicator organisms. It can provide results within four to five hours. Current work is attempting to understand the relationship between qPCR data and the risk of disease.

Environmental Sample Processor (ESP) is an instrument that automatically samples and tests water for the DNA of specific target organisms. It is currently being used to watch for red tide and other harmful algae and a version might someday be able to monitor beach water quality.

Alternative indicator organisms are being studied for use in water quality monitoring. These might be better correlated with the presence of pathogens and so reflect risk of disease. Research is also underway to identify organisms that specifically indicate the presence of human fecal contamination or the source of non-human fecal material.

What About Shellfishing?

Shellfishing is a separate, but related, topic. Safety standards for the harvest and consumption of shellfish are established separately by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are administered by the National Shellfish Sanitation Program.

Because of the differences between monitoring shellfish and bathing water, a swimming beach may be closed while nearby shellfishing areas remain open, and vice versa. Contact the town shellfish warden or similar authority to find out if shellfish are safe to eat when a nearby beach has recently been closed.

News & Insights

Summer’s coming: Will Cape Cod beaches be safe?

Beach parking lots across Cape Cod are closed to reduce the spread of COVID-19. As summertime approaches, will the beach crowds that normally show up after Memorial Day will be staying away this year? WHOI microbiologist Amy Apprill weighs in.

News Releases

Study Looks at Gray Seal Impact on Beach Water Quality

[ ALL ]

From Oceanus Magazine

The Return of the Seals

WHOI biologist Rebecca Gast examines whether the recovered and thriving population of gray seals in Cape Cod waters has affected water quality off the beaches they frequent.

Marine Microplastics

Marine Microplastics  Oil Spills

Oil Spills  Radiation

Radiation