Coral reefs are colorful places. Bright-colored fish, anemones, and crustaceans dart, flutter, and creep among patches of coral. Corals themselves can be brightly colored. More often, they are muted browns and greens. Although a coral may seem somewhat rock-like, the hard structure that many people think of as coral is just a skeleton. In living coral, that skeleton is covered with tiny polyps. These tentacled polyps are all extensions of the same animal. Over time, they build up the skeleton, which provides them with a safe place to live. Corals, in turn, provide the base for coral reefs, which are home to countless marine animals.

Coral polyps, themselves, don’t have much color. Their body tissues are nearly transparent. But they form a symbiotic relationship with tiny algae. It’s these algae, called zooxanthellae (belonging to the dinoflagellate family Symbiodinaceae), that give corals their color. They also provide corals with food. Like plants, the algae use sunlight to make food from carbon dioxide and water in a process called photosynthesis. Most of the food they make feeds the corals. In return, corals provide the algae with a place to live.

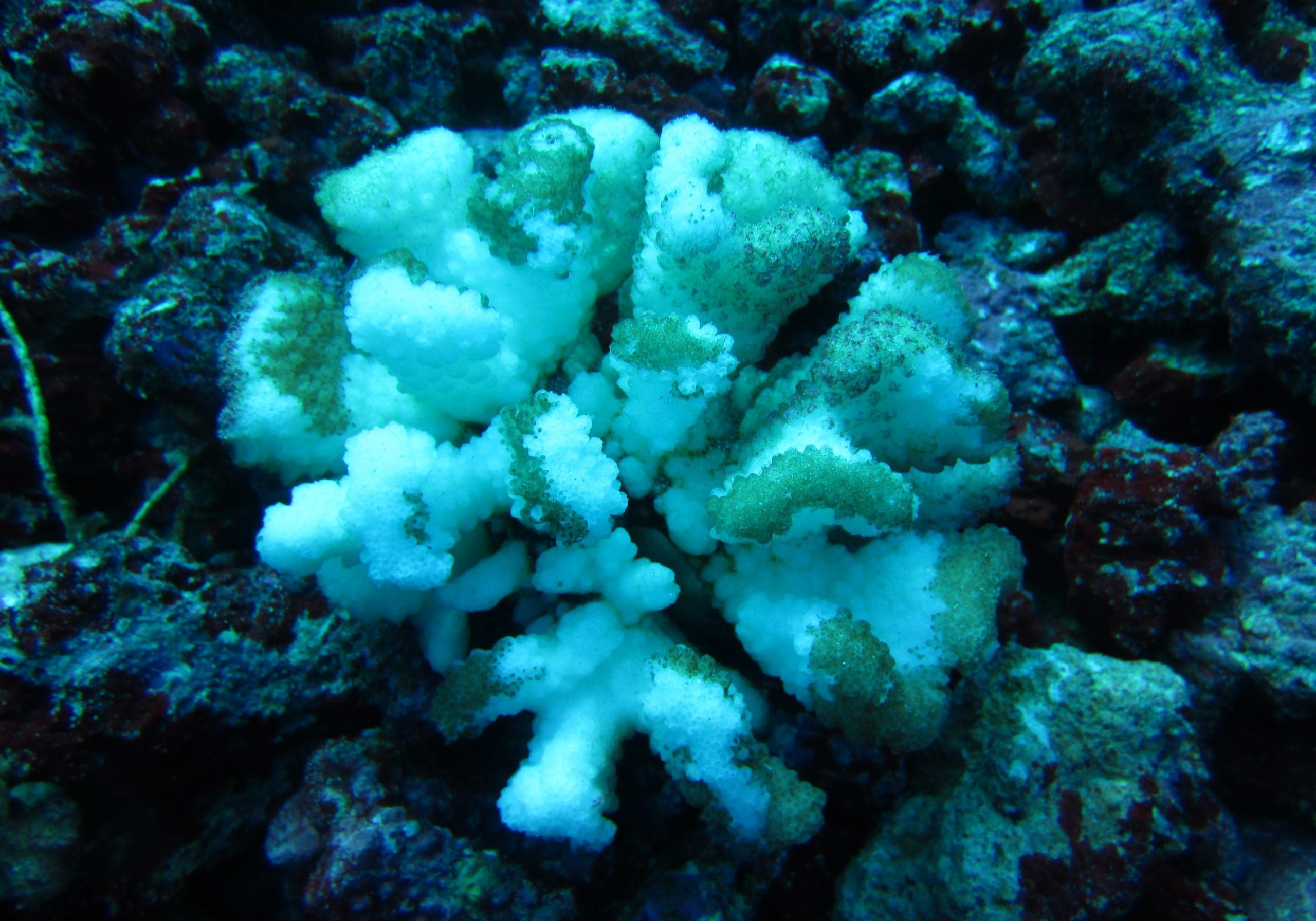

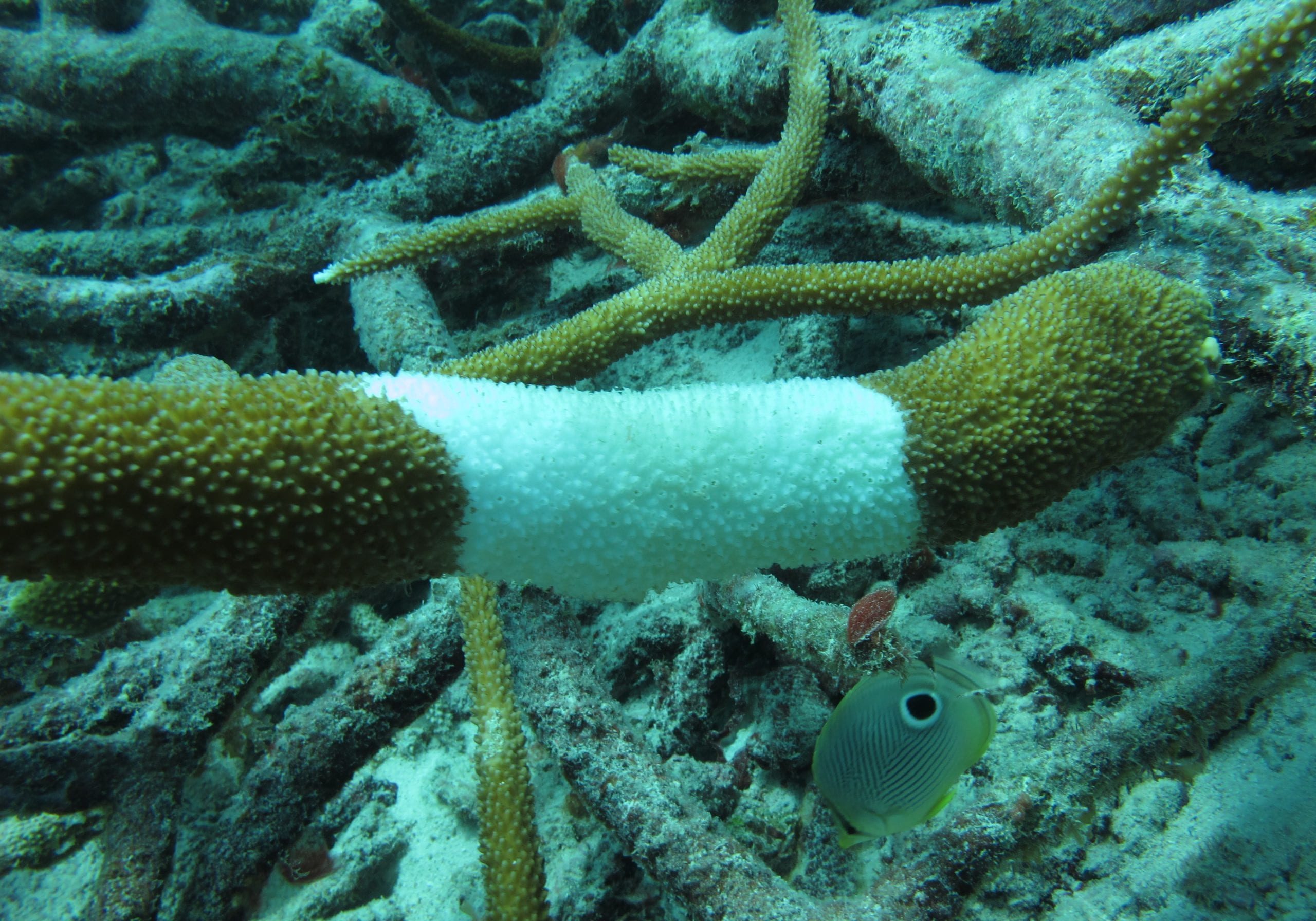

When corals become stressed, the relationship between corals and zooxanthellae can break down. The zooxanthellae and/or their coloration are lost from the coral. This causes the coral to turn a ghostly white, which is commonly referred to as bleaching. The specific process causing coral bleaching is an active area of research.

Bleaching can happen when the water gets too warm. Or when it becomes polluted. Or even when corals are exposed to too much sunlight. Under warm temperatures, even normal levels of sunlight can cause bleaching. Or, if something changes in the environment to expose a coral to more light than before, it can also bleach.

Corals aren’t dead when they bleach. They’ve simply lost their color. But when the zooxanthellae leave, they take with them the coral’s main source of food. Corals can snag tiny bits of food from the water with their tentacles. But most corals cannot survive just on feeding.

Sometimes zooxanthellae will return to their coral hosts. When this happens, corals can become healthy and begin to grow again. But once they have bleached, corals need time to fully recover.

Coral bleaching is a common problem and one that scientists are working to better understand. They hope to find ways to help corals recover from bleaching events. And they’re working to make corals more resistant to the stressors that cause bleaching. This would protect the reefs that are home to so much marine life.

LEARN MORE

Abrupt Climate Change

Earth’s changing climate is raising concerns that it could respond in abrupt and unexpected ways, making it difficult for human society to adapt.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation. Coral Bleaching. https://www.barrierreef.org/the-reef/coral-bleaching

NOAA. Coral Bleaching—A Review of the Causes and Consequences. A Reef Manager’s Guide to Coral Bleaching, chapter 4. https://www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/reef_managers_guide/reef_managers_guide_ch4.pdf

NOAA. Coral Bleaching—Background. https://www.coral.noaa.gov/education/bleaching-background.html

NOAA. What is coral bleaching? https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/coral_bleach.html

DIVE INTO MORE OCEAN FACTS

How is beach sand created?

Beaches can be white, black, green, red and even pink. What creates those different colors? Why is some sand soft and fine, but other types feel rough? Where does beach sand come from, anyway?

How does the ocean affect storms?

Under the right conditions, some of those storms can grow into large tropical storms. Or even monstrous hurricanes.

Why do emperor penguins toboggan?

Learn why Emperor penguins slide around on their bellies or “toboggan” when they’re on the move in Antarctica.

How are seashells made?

One of the most striking features of our beaches is seashells. Their whorls, curves, and shiny iridescent insides are the remains of animals. But where do they come from?