In 1998, operators of a Japanese remotely operated vehicle (ROV) named KAIKO were surveying the depths of the Mariana Trench in the Pacific Ocean when they spotted something shocking on the vehicle’s camera: a single-use plastic bag floating idly some 6.7 miles (10.8 kilometers) down at the Earth’s deepest point. Since then, it’s become clear that no part of the ocean is immune to plastic pollution, and it’s not surprising why, considering how much of it we generate.

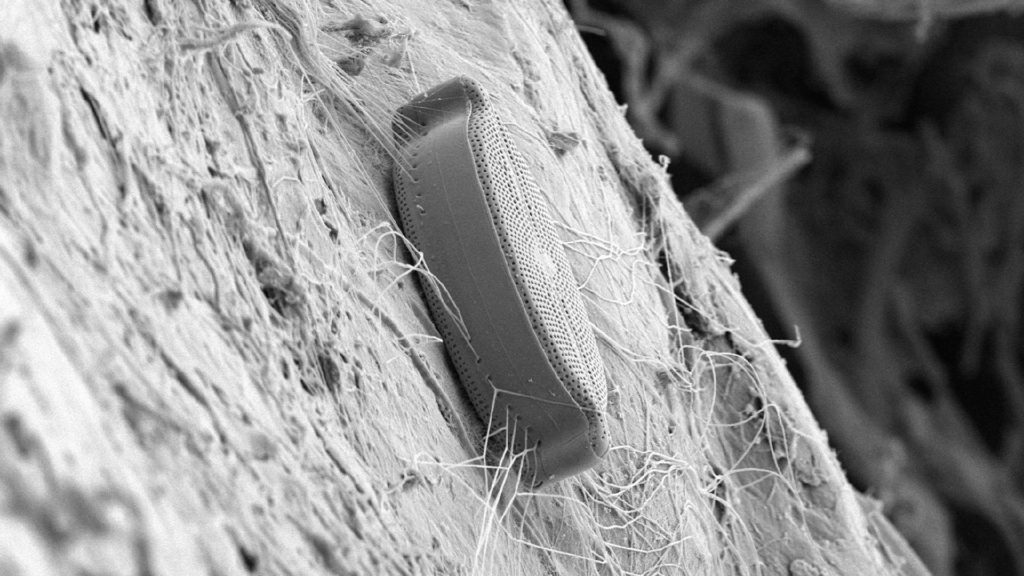

An image from a high-powered microscope reveals a microbe that has colonized a microplastic fragment, which over time will weigh it down causing it to sink. (Photo by © Erik and and Linda Amaral-Zettler, NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research)

Humans produce a whopping 390 million tons of plastic each year, of which 14 million tons will end up in the ocean, making up at least 80 percent of all debris found in the sea, according to a 2021 United Nations Environmental Programme report. This marine debris makes its way into the ocean chiefly through rivers, stormwater runoff, and via wind that blows trash off of coastal landfills. How plastic makes its way into the deep sea, however, has a lot to do with its chemical composition.

At the sea surface, plastics are exposed to corrosive saltwater, ultraviolet (UV) rays, and crashing waves that can break up these materials into finer particles. But not all plastics are created equal. Some, like Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC)—found in products like credit cards, piping, and IV medical bags—are designed with durability in mind and can take much longer to degrade (up to 450 years, in some cases). Others, like polyethylenes—found in products like plastic grocery bags, soda and detergent bottles, and even children’s toys—are not as resistant to UV light or stress cracking and can break down at much faster rates.

While the ocean chops, dices, and minces this plastic into smaller bits, organisms from bacteria to barnacles amass on them. This process, known as biofouling, can weigh plastics down, sinking them to lower depths. Over time, these particles can rain down alongside organic fecal matter, or marine snow, and may be eaten by midwater and seafloor organisms that mistake them for food.

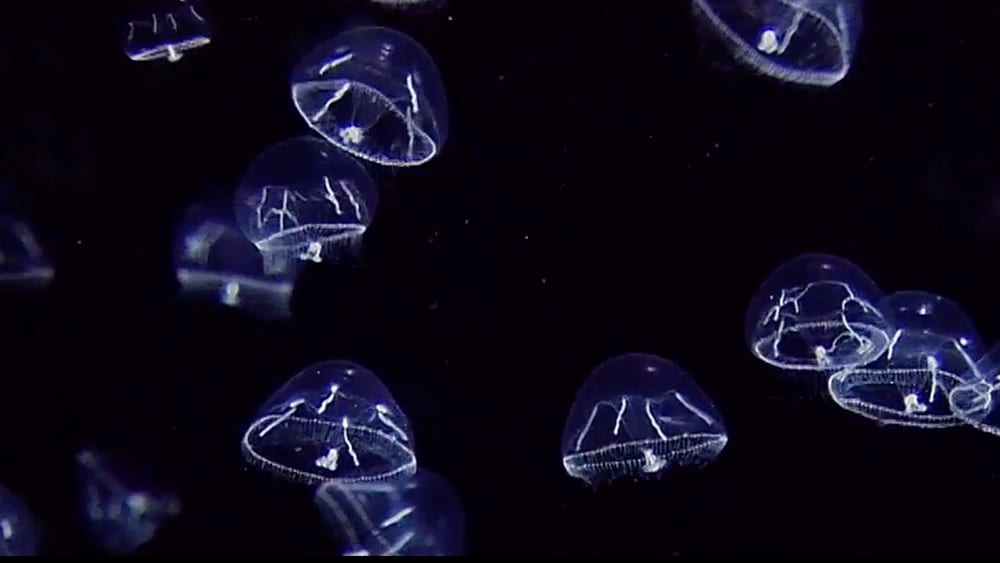

Plastic debris scene from Japanese ROV KAIKO on a 1998 dive off of the Bosō Peninsula, depth 9203 meters (30,193 ft). (Footage courtesy of © JAMSTEC)

Plastics that aren’t consumed will eventually land on the seafloor, where deep-sea currents, called thermohaline currents, can sweep them into trenches, where they accumulate. This “trench trap” is so efficient at funneling debris, in fact, that researchers have detected plastics in nearly all of the world’s deepest trenches, including the Mariana Trench (10,924 meters / 35,839 feet), the Philippine Trench (10,540 meters / 34,580 ft ), the Cayman Trench (7,686 meters / 25,216 feet), and the Java Trench (7,450 meters / 24,440 feet).

Deep-sea experts are able to document this pollution through footage captured by submersibles like KAIKO, but also from sediment samples taken by special digging tools called box corers that are lowered down to the seafloor from ships. In the Atlantic and Indian oceans, as well as in the Mediterranean Sea, sediment surveys reveal that the seafloor holds exponentially higher concentrations of microplastics (more than four orders of magnitude) than surface waters.

LEARN MORE

Marine Microplastics

Marine microplastics are small fragments of plastic debris that are less than five millimeters long. Some microplastics, known as primary microplastics, are “micro” by design

Bongiovanni, C., Stewart, H.A. and Jamieson, A.J. (2021). High-resolution multibeam sonar bathymetry of the deepest place in each ocean. Geosciences Data Journal, 9(1), 108-123. https://doi.org/10.1002/gdj3.122

Chiba, S., Saito, H., Fletcher, R., Yogi, T., Kayo, M., Miyagi, S., Ogido, M., & Fujikura, K. (2017). Human footprint in the abyss: 30 year records of deep-sea plastic debris. Marine Policy, 96, 204-212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.03.022

Kane, I.A., Clare, M.A., Miramontes, E., Wogelius, R., Rothwell, J. J., Garreau, P., & Pohl, F. (2020). Seafloor microplastic hotspots controlled by deep-sea circulation. Science, 368(6495), 1140–1145. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba5899

Jamieson, A.J., Brooks, L., Reid, W.D., Piertney, S.B., Narayanaswamy, B., & Linley, T.D. (2019). Microplastics and synthetic particles ingested by deep-sea amphipods in six of the deepest marine ecosystems on Earth. Royal Society Open Science, 6(2), 180667. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.180667

Jamieson, A.J., Stewart, H.A., Weston, J.N.J., Lahey, P., & Vescovo, V. (2022). Hadal Biodiversity, habitats and potential chemosynthesis in the Java Trench, eastern Indian Ocean. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.856992

Jamieson, A.J. and Onda, D.F.L. (2022). Lebensspuren and müllspuren: Drifting plastic bags alter microtopography of seafloor at full ocean depth (10,000 m, Philippine Trench). Continental Shelf Research, 250, 104867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2022.104867

Shimanaga, M., Yanagi, K. (2016).The Ryukyu Trench may function as a “depocenter” for anthropogenic marine litter. Journal of Oceanography, 72(6), 895–903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10872-016-0388-7

Woodall, L. C., Sanchez-Vidal, A., Canals, M., Paterson, G. L., Coppock, R., Sleight, V.A, Calafat, A., Rogers, A. D., Narayanaswamy, B., & Thompson, R. C. (2014). The deep sea is a major sink for microplastic debris. Royal Society Open Science, 1(4), 140317. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.140317

DIVE INTO MORE OCEAN FACTS

Can AI help us explore the ocean?

Learn how scientists at WHOI are using AI, like the software “Spock,” to enable autonomous underwater robots, such as Nereid Under Ice and CUREE, to study marine life and explore ocean environments.

Are corals plants, animals, or rocks?

The base of a coral reef is coral, but what is coral? If you look at a piece of coral that washed up on shore, it’s solid and tough with rough edges and little pits.

How does bioluminescence work?

Deep in the ocean there’s very little sunlight. But if you could swim down there, it would look a bit like the night sky. Why is this?

What is a marine heatwave?

From waning winds to warmer atmospheres, here is the recipe for sudden temperature spikes in our ocean