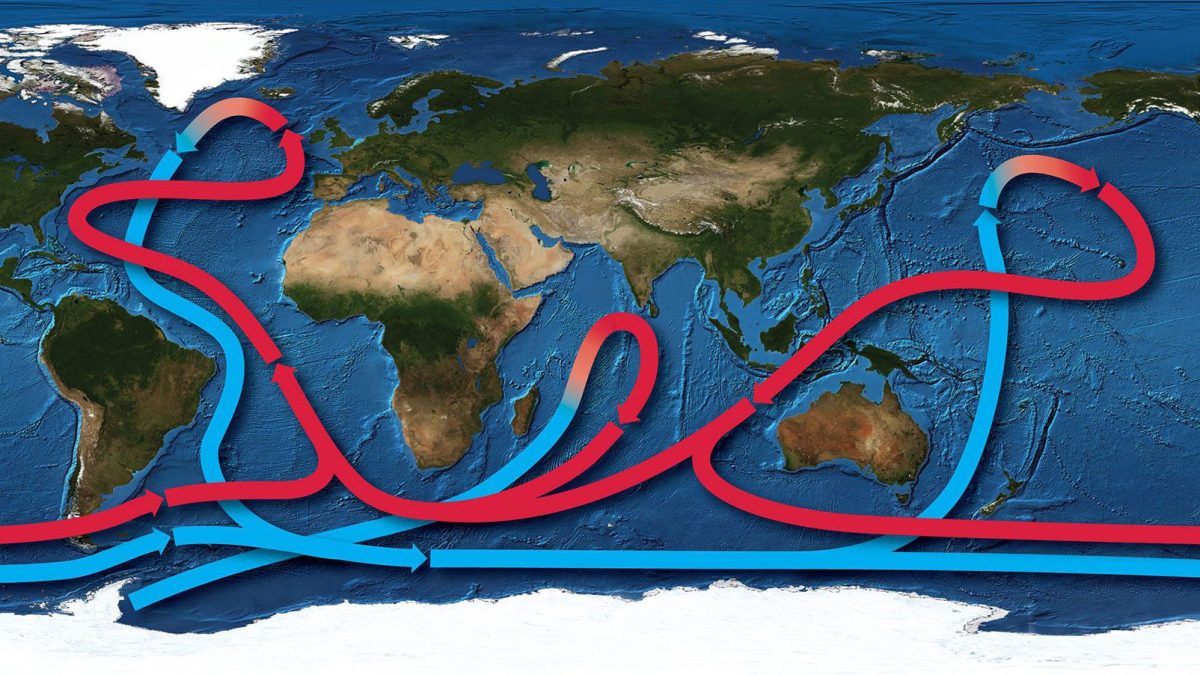

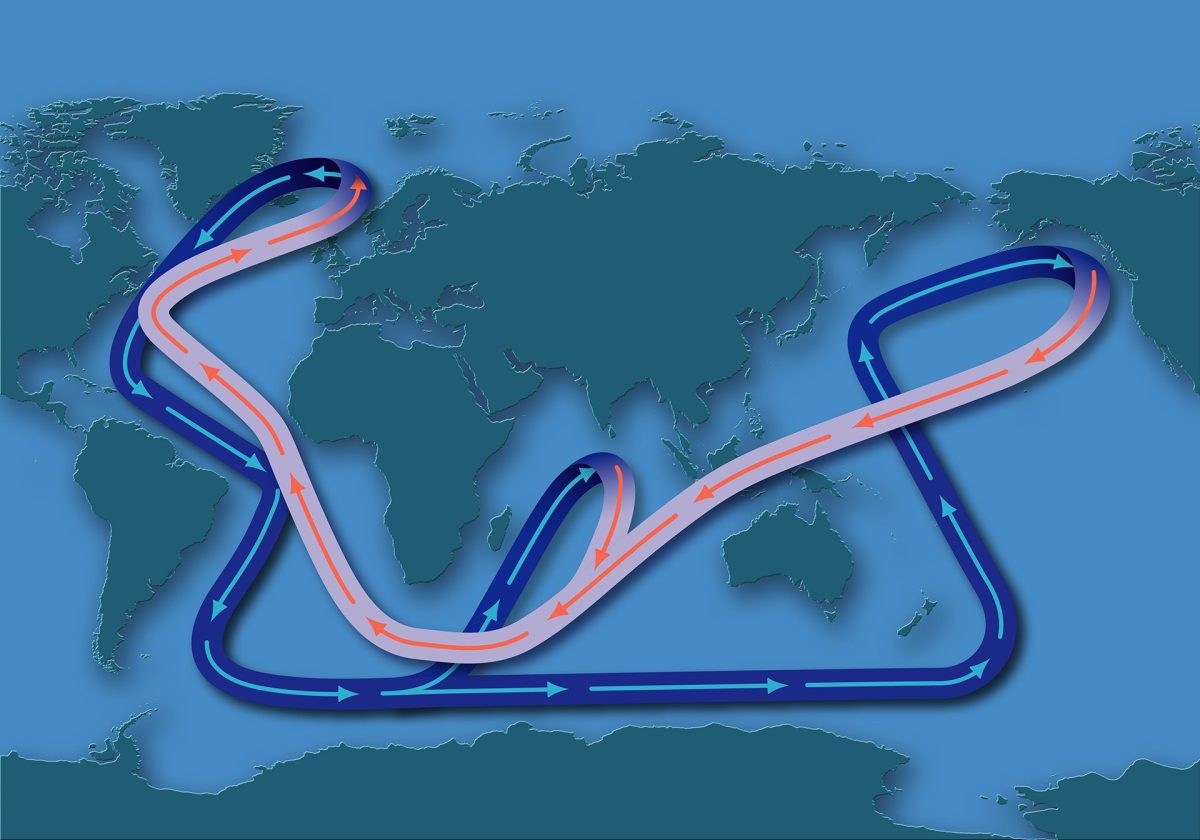

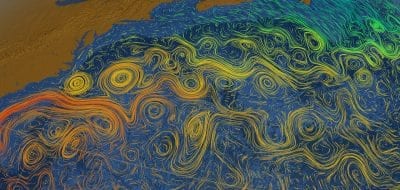

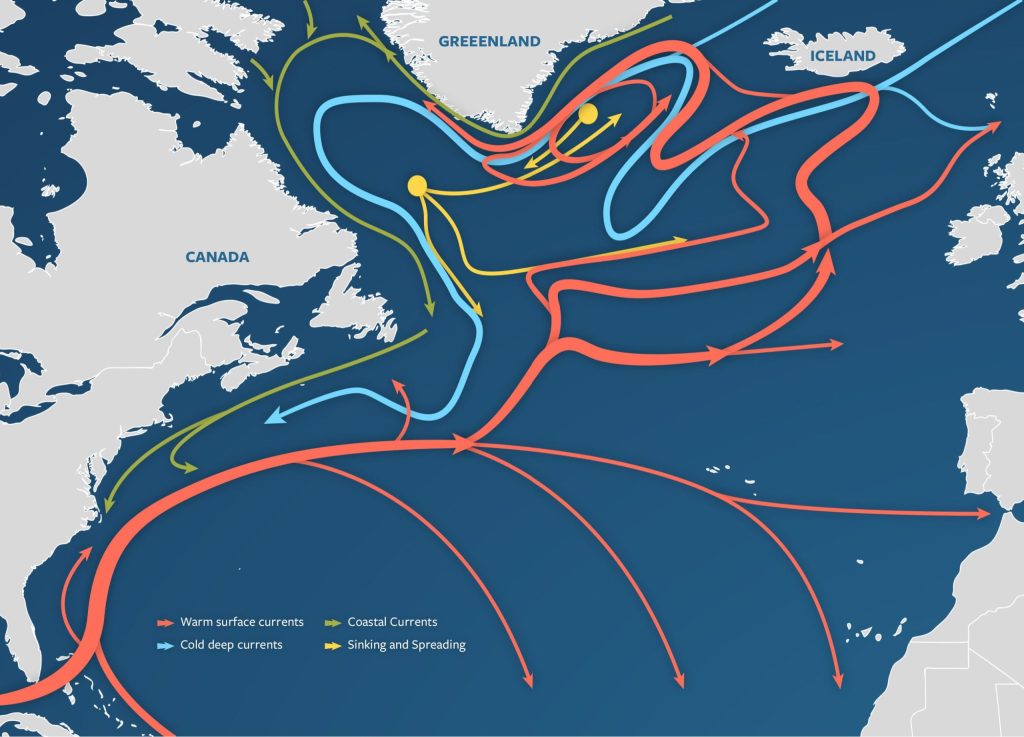

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) propels warm surface water from the q to high-latitude regions. There, the water encounters strong winds and cold air temperatures, which causes it to become colder and denser. This cold, dense water sinks into the deep ocean and then is conveyed back southward at depth, creating a conveyor belt-like loop. (Illustration by Eric S. Taylor, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

What is the AMOC?

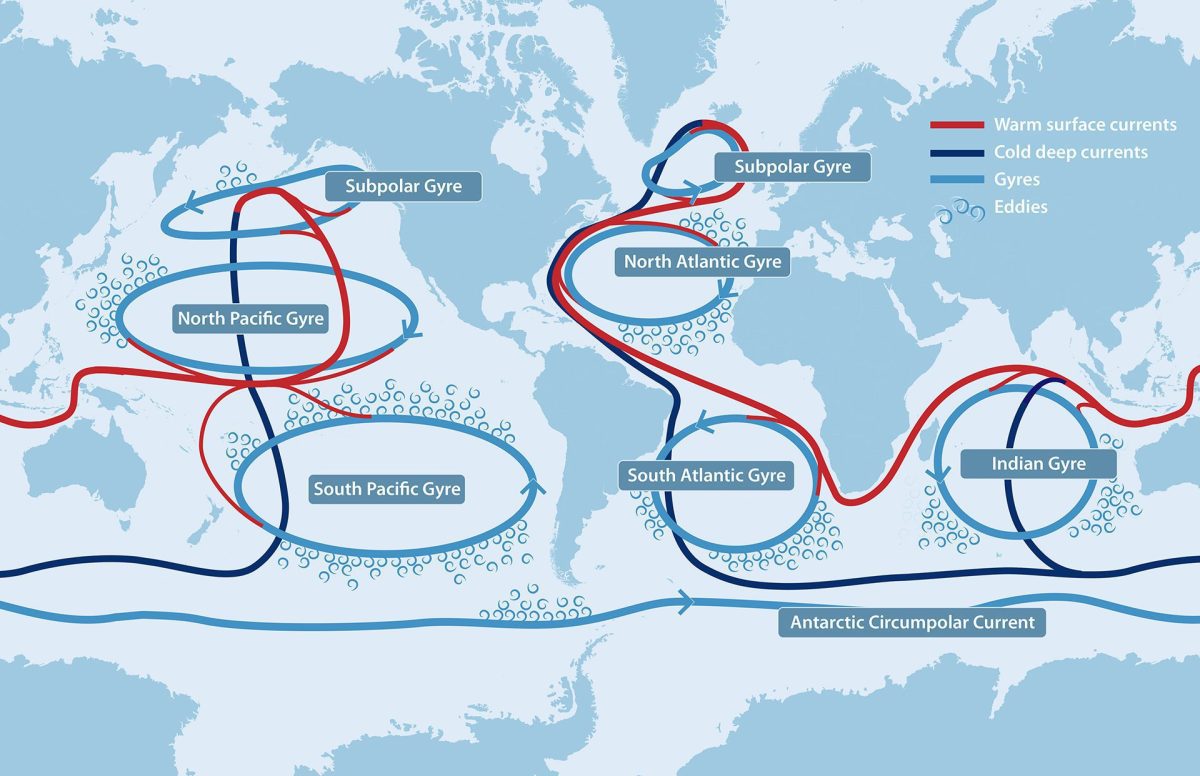

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is part of a system of currents that transport water throughout the world’s oceans. Driven by a combination of temperature and salinity (salt), currents circulate water over millennia, distributing heat, moisture, and nutrients as they go.

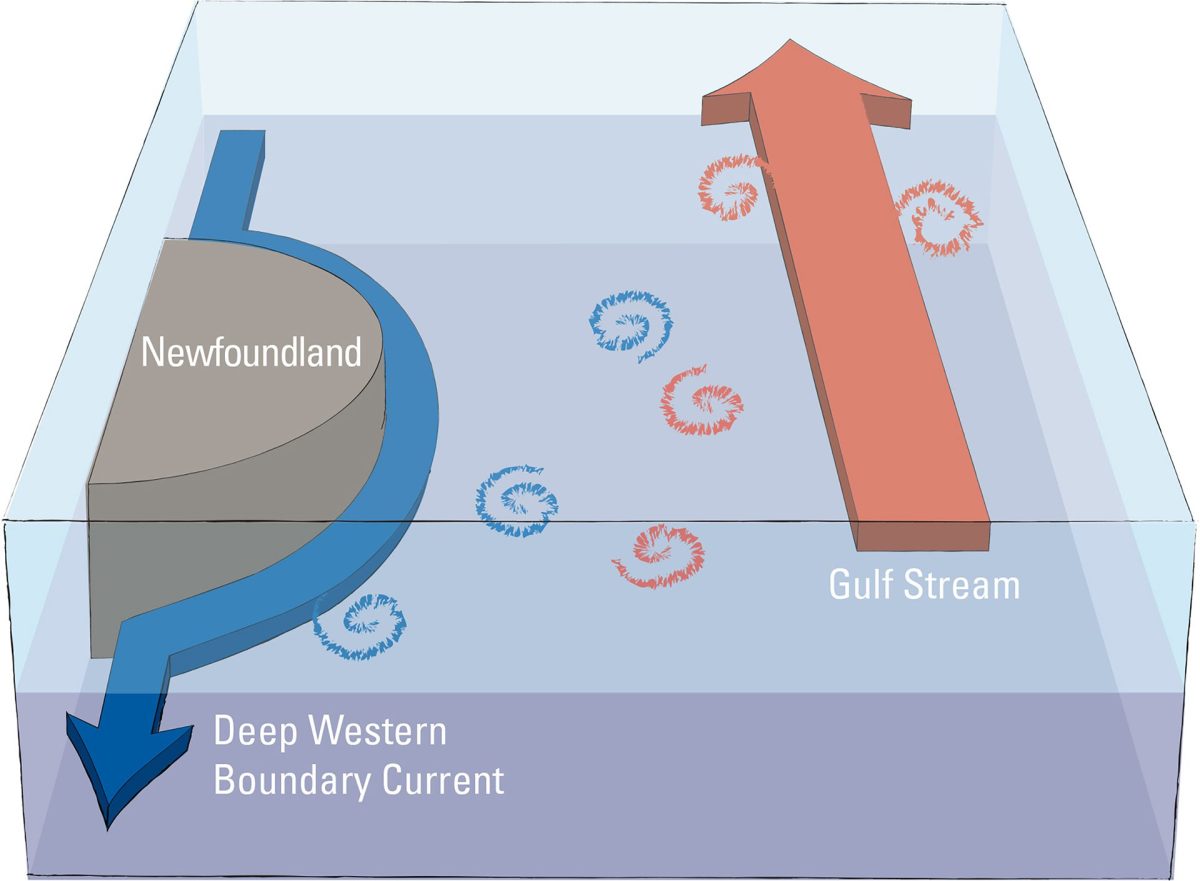

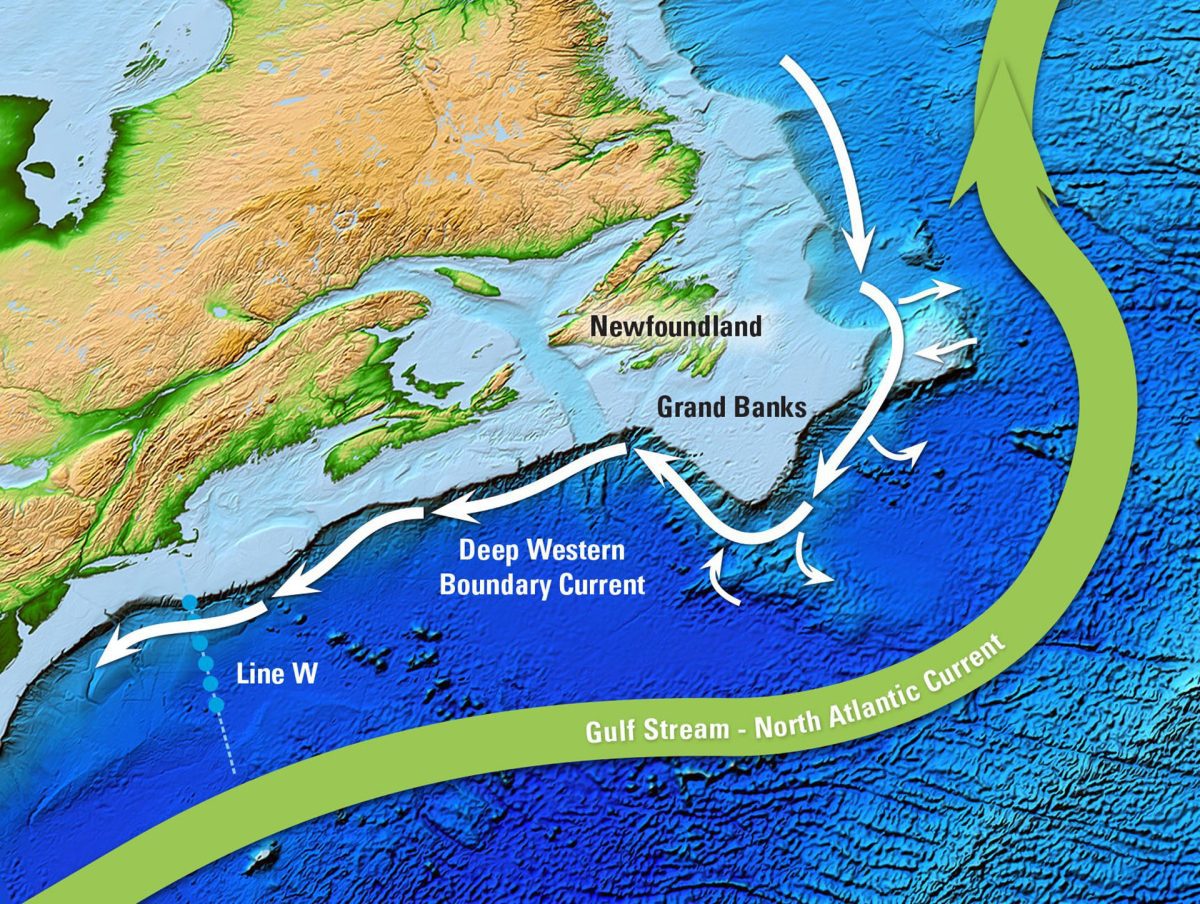

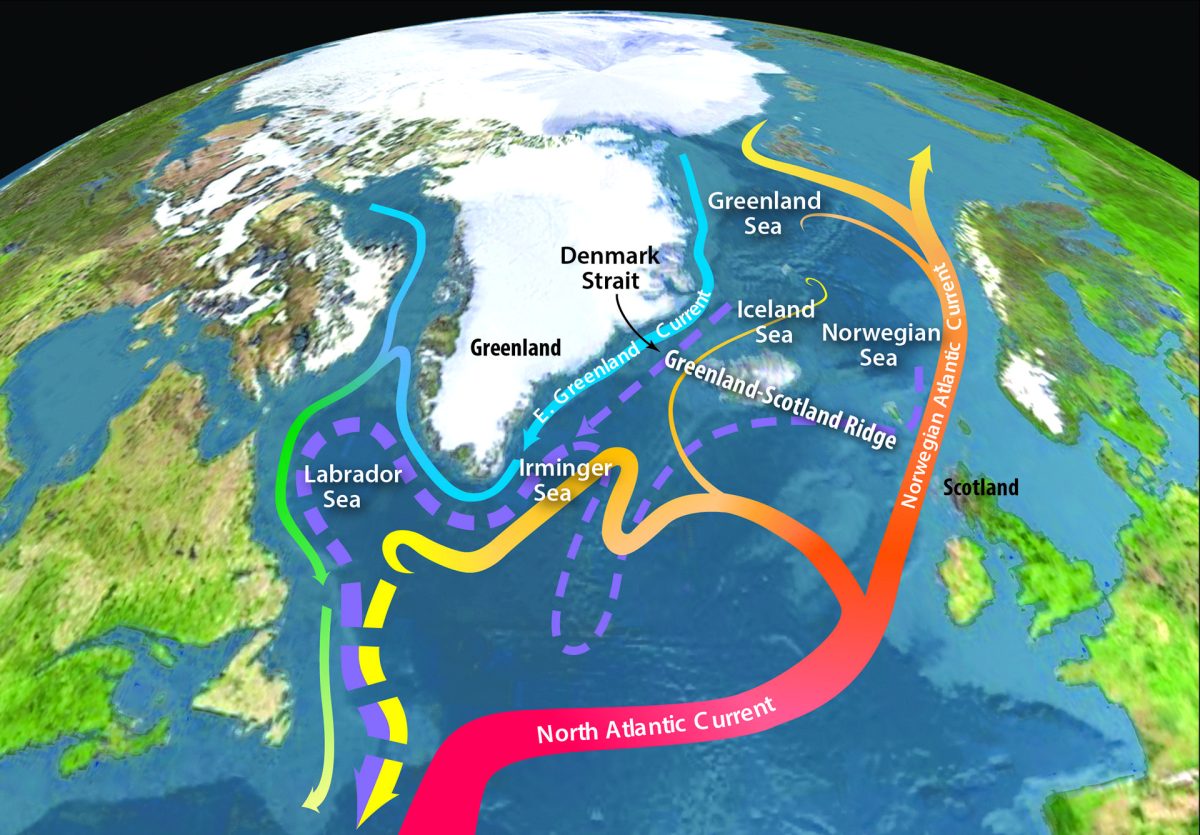

The Gulf Stream, as part of the AMOC, transports a current of warm water from the Florida Straits to the Grand Banks off Newfoundland. From there, the North Atlantic Current travels across the ocean to the Norwegian Sea, where it loses heat to the atmosphere and cools. The water here is salty, which allows it to supercool below 0° Celsius (32° Fahrenheit). Cold, salty water is denser than warmer, fresher water, and the water here begins to sink, pulling more water from the Gulf Stream behind it in a process that drives the AMOC. After sinking, the cold, deep waters tend to flow south along the sea floor towards the Antarctic. These waters then circulate through the Indian and Pacific Oceans. They eventually mix with the water column and return to the surface.

Why is it important?

Because the AMOC redistributes heat from the tropics to the Arctic, it plays a large role in climate. The Gulf Stream brings heat to Iceland and Northern Europe, which allows for a much more temperate climate than these regions would otherwise experience. The deep, southbound current carries cold water to the Antarctic. When it returns to the surface, it brings nutrients from the depths that support marine life.

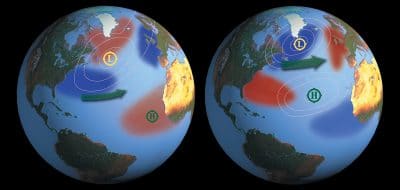

Movement of heat from the tropics to northern climes impacts rain and snowfall patterns—not only in the North Atlantic, but around the globe. There is concern that the AMOC could weaken when ice sheets in Greenland melt, releasing large quantities of fresh water into the ocean. If this water, which is less dense than saltwater, reaches the North Atlantic Current, it could potentially slow the rate at which waters in the AMOC sink to the seafloor. The result would be a slowed conveyor belt that redistributes less heat. This could have profound impacts on not only ocean temperatures, but also air temperature and rainfall patterns. A weakened AMOC could lead to colder temperatures in Europe, along with greater snowfall in winter. Shifting precipitation patterns can cause drought in some areas and excessive rainfall and flooding in others, both of which have a huge impact on agriculture.

Some research suggests that nutrients within the ocean ecosystem would be impacted as the AMOC weakens, as fewer nutrients would be transported to areas where they have historically been available. This could affect all kinds of sea life, from plankton and sea birds to fish and whales. The AMOC also moves carbon deep into the ocean, removing it from atmospheric circulation. In this way, it plays an important role in mitigating climate change.

What are ocean scientists doing to better understand the AMOC?

To understand past conditions, paleoclimatologists use cores from corals and the seafloor that provide an extensive record of the ocean’s chemistry going back in time. They have amassed ample evidence that abrupt shifts in the AMOC have happened in the past during periods of warming. Most climate changes happen on the order of centuries or longer, but a weakened AMOC can happen rapidly, in a decade or less. The potential for sudden, catastrophic shifts in Earth’s climate has scientists around the world collecting data on the AMOC to better understand its current state and learn how it might change in coming years.

One major challenge in predicting changes to the AMOC lies in a lack of data. Scientists have only collected data on the AMOC since 2004, and this short window of time may reflect natural oscillations in the flow of these currents that are not necessarily caused by climate change. But thousands of sensors now monitor the ocean. Some are anchored to the sea floor while others are free-swimming autonomous robots. Both types of devices send their data to shore via satellite, providing a glimpse of current conditions that researchers can incorporate into models to help forecast changes in the AMOC.

Using those data and models, current research is investigating the time scales of shifts in the AMOC, as well as how a weakened AMOC could contribute to sea level rise in the North Atlantic. Researchers are looking into movement of freshwater as it enters the ocean to understand where and how it might impact the AMOC as ice sheets in Greenland continue to melt. And they are reconstructing past climate shifts and changes in the AMOC to better understand how the two are linked, so they can continue to build better models that will more accurately predict coming changes.

Caesar, L. et al. Current Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation weakest in last millennium. Nature Geoscience. Vol. 14. February 25, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41561-021-00699-z.

IPCC, 2019: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, chapter 6: Extremes, Abrupt Changes, and Managing Risks [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 755 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/chapter-6/

Showstack, Randy. What’s happening with the AMOC? Oceanus. August 3, 2023. https://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/feature/whats-happening-with-the-amoc/

Siddall, G. SeaCycler Deployment. Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program. June 1, 2016. https://www.o-snap.org/seacycler-deployment/

Tuchen, F.P. et al. Transports and pathways of the tropical AMOC return flow from Argo data and shipboard velocity measurements. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. Vol. 127. doi: 10.1029/2021JC018115.

Whitt, D.B. and M.F. Jansen. Slower nutrient stream suppresses Subarctic Atlantic Ocean biological productivity in global warming. PNAS, vol. 117. June 22, 2020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2000851117.

WHOI. Atlantic Ocean circulation at weakest point in 1,600 years. April 11, 2018. https://www.whoi.edu/press-room/news-release/atlantic-ocean-circulation-at-weakest-point-in-more-than-1500-years/