Icebergs drift into the port of Tasiilaq in Greenland, where WHOI scientists and colleagues from the University of Maine were based this summer while measuring ocean temperatures in nearby Sermilik Fjord. The goal was to investigate if the recent acceleration of Greenland's ice sheet is due to ocean warming ocean, said WHOI researcher Fiamma Straneo. Scientists collected measurements using a small boat, which they could navigate easily through the maze of icebergs and sea-ice bobbing in the fjord. The larger vessels in the background are (from left) the local ferry, a Faeroese fishing boat, and a visiting police boat from Nuuk. (Photo by Fiamma Straneo © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

What is ocean warming?

Rising ocean temperatures are driving unprecedented changes in global marine ecosystems, sea levels, and weather patterns. As heat transforms the ocean, threats to food supplies, economies, and weather multiply, putting human and environmental health at risk.

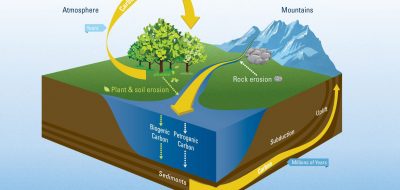

The ocean is a vital part of Earth’s climate system: It helps moderate climate and slow the impacts of global warming. Covering 70 percent of the planet, the ocean soaks up heat trapped in the atmosphere by carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

Increasing ocean heat is closely linked to increases in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, making the ocean an excellent indicator of how much Earth is warming. Since 1971, the ocean has absorbed 90 percent of the excess energy added to Earth's climate by burning fossil fuels and other human activities.

The ocean’s surface layer, home to most marine life, takes most of this heat. As a result, the top 700 meters (2,300 feet) of the global ocean has warmed about 1.5°F since 1901. And scientists recently found that the rate of warming in the top 6,500 feet of the ocean over the past few decades was about 40 percent higher than previously estimated.

Water can hold more heat than land or air, so it warms more slowly, but this rate is still alarming. The ocean won’t hold this heat forever. It will eventually be released, feeding back into the climate system and causing further warming.

Why is ocean warming important?

Even the seemingly slight increase of 1.5°F in ocean temperature represents an enormous amount of heat, one large enough to transform marine biodiversity, change ocean chemistry, raise sea levels, and fuel extreme weather. Earth is already experiencing the consequences of these changes, impacting property, lives, and livelihoods—and not just in coastal areas.

Rising ocean temperatures are connected to some weather extremes and can lead to more intense hurricanes, heavier rainfall, and snowstorms. Warmer sea surface temperatures influence weather patterns and shift precipitation, causing some regions to experience intense rainstorms and flooding and exacerbating drought conditions and wildfire risks in others.

Warmer ocean waters also contribute to rising sea levels, and this thermal expansion could be the biggest driver of sea level rise over long time scales. Because water becomes less dense and expands as it heats up, it occupies more space and causes sea levels to creep up. Polar ice sheets thin and erode in response, pushing levels even higher. Sea level rise has different rates and magnitudes in different places; scientists estimate sea level could rise at least 15 inches by 2100 in some areas, potentially displacing millions worldwide.

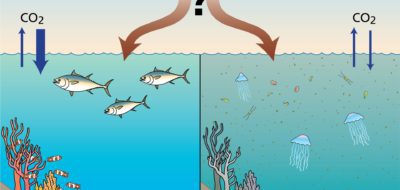

Marine life will suffer the most due to unprecedented ocean warming. Fish species now migrate north to find cooler temperatures and food sources, impacting communities and economies that depend on fishing. Rising ocean temperatures contribute to oxygen-depleted ocean dead zones in large coastal and open ocean areas, rendering them largely uninhabitable by marine life.

Hotter oceans can hold more carbon dioxide, which causes seawater to become more acidic. This phenomenon, known as ocean acidification, harms corals, clams, snails, and many other marine organisms, mainly by dissolving their calcium carbonate shells and skeletons.

Warmer ocean waters also encourage frequent, lengthy marine heatwaves, where temperatures can jump several degrees or more above average. These prolonged periods of heat wreak havoc on marine health and increase the risk of massive bleaching events on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef and other sensitive coral ecosystems.

MIT-WHOI Joint Program graduate students Alice Alpert (left) and Liz Drenkard (center), and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service representative Kelsie Ernsberger (right), snorkel above a large coral at an atoll in the central equatorial Pacific in 2012. Alpert, Drenkard, and WHOI scientist emeritus George Lohmann, with the conservation organization Pangaea Exploration, sailed 2000 miles to these remote coral islands. They sampled seawater and coral and deployed instruments, part of a larger study by WHOI scientists Anne Cohen, Kris Karnauskas, and Delia Oppo aimed at gaining a better understanding of climate change and potential impacts of ocean warming and acidification on coral reef communities. (Photo by Chip Young, NOAA © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Is the ocean warming the same everywhere?

The ocean is warming unevenly, with rates varying according to the depth and region of the world.

Scientists use measurements from satellites, ships, and an array of tools and technology combined with historical records to understand how and where ocean temperatures are rising.

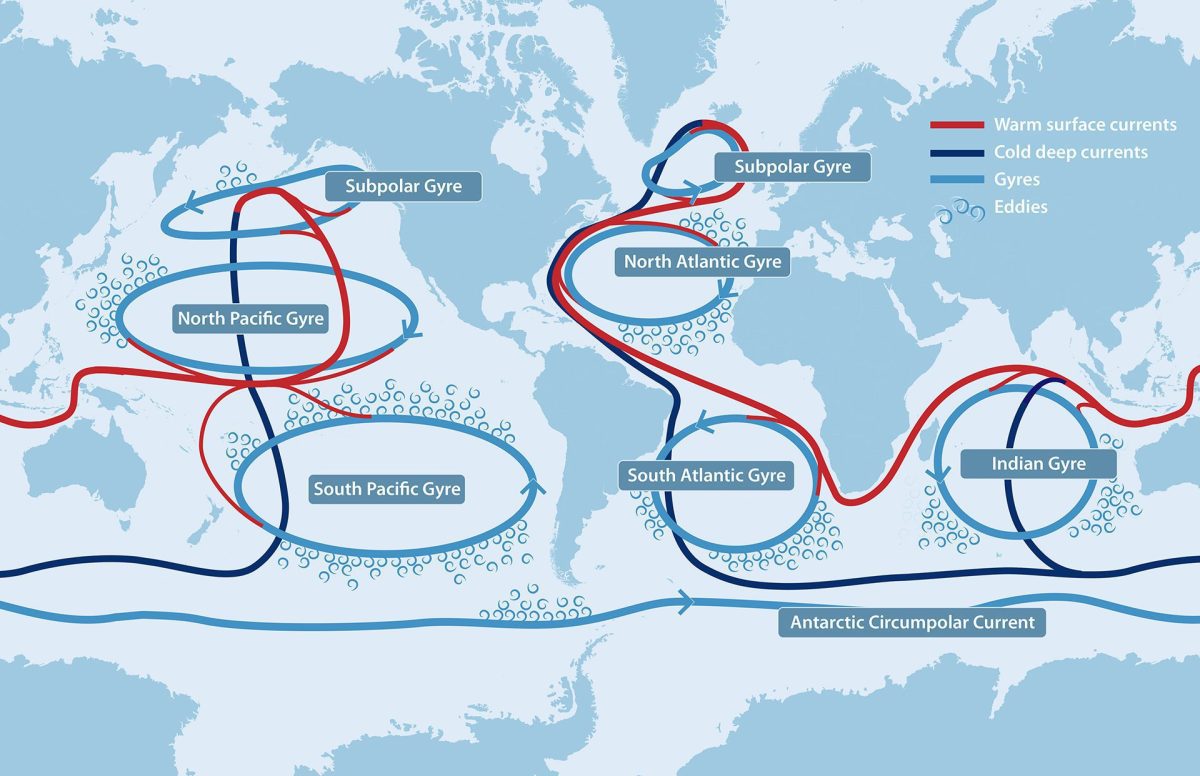

Their work reveals temperatures are rising throughout the ocean, but the surface down to about 10 feet is warming the most. Regional fast-warming hot spots include parts of the North Atlantic and Indian Ocean, and the Arctic and Southern Oceans, where hotter ocean temperatures contribute to ice sheets and glaciers melting.

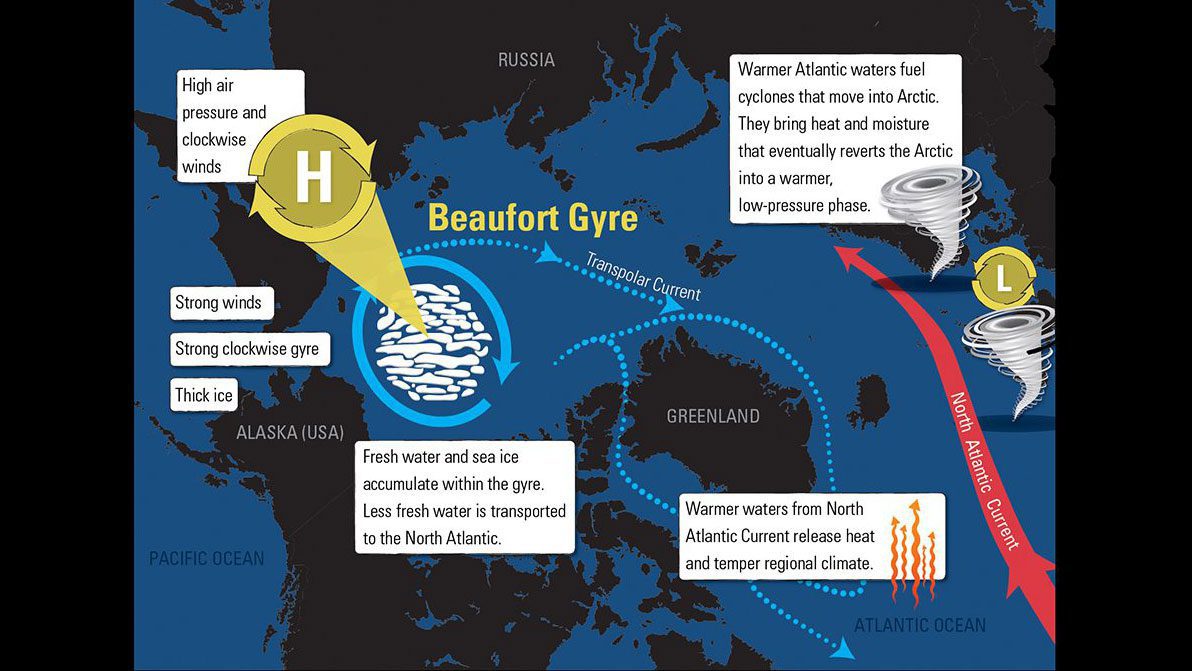

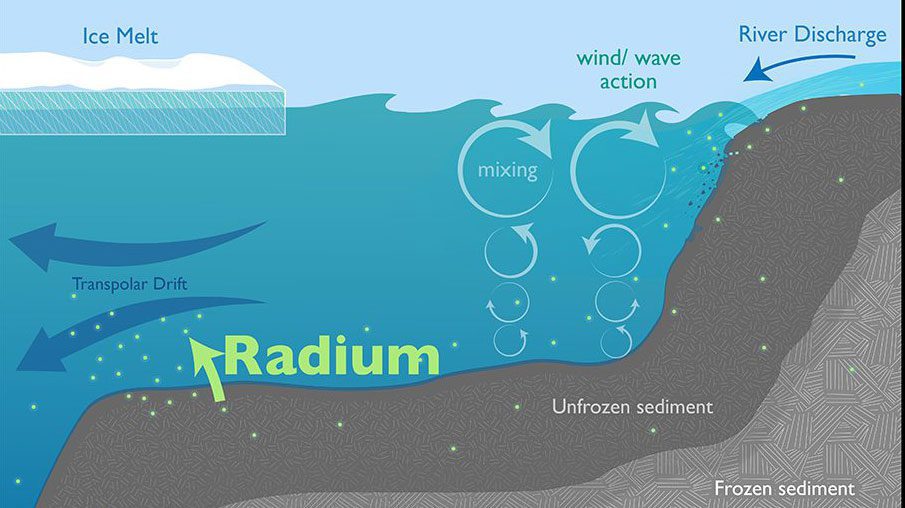

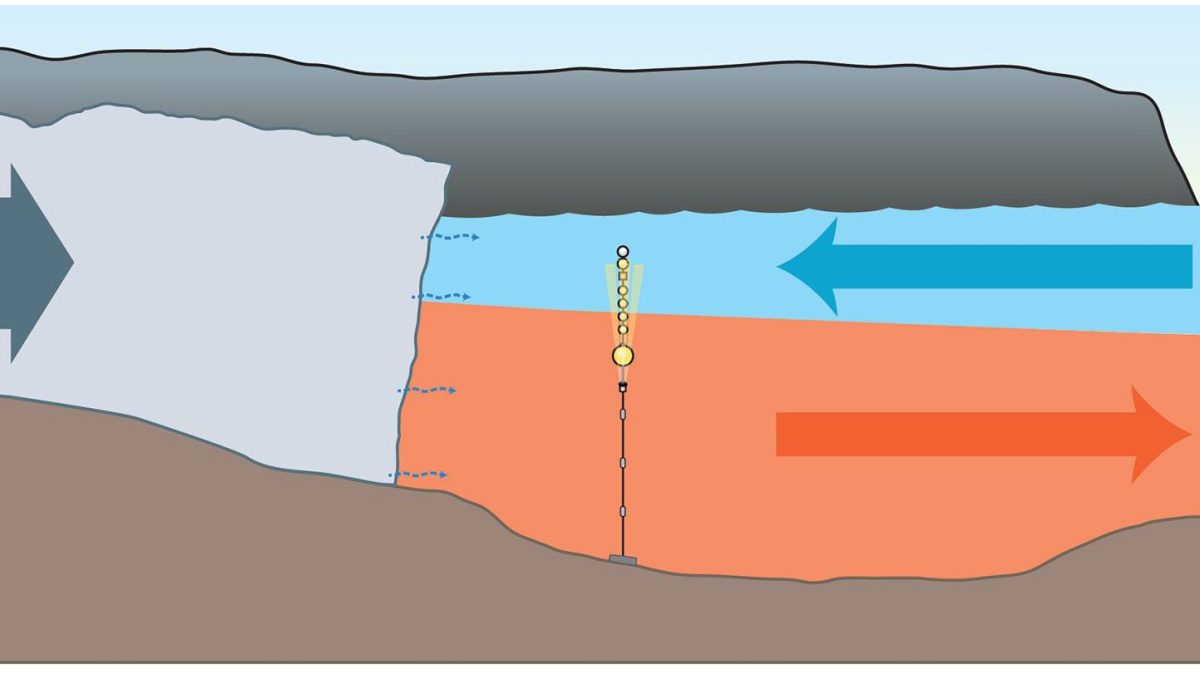

As polar ice melts into the sea, the freshwater changes the density of seawater. Cold, salty water usually sinks, but when it’s fresher and warmer, it changes ocean circulation patterns and heat distribution throughout the ocean.

The powerful currents that move and distribute heat throughout the ocean also drive uneven warming. When those currents carry warm water masses to cooler latitudes and deeper levels, those areas begin heating up.

How does ocean warming impact the weather?

Rising ocean temperatures are making some extreme weather events worse by supercharging storms and altering global weather patterns.

Warm surface waters provide energy for hurricanes and other tropical cyclones, increasing their frequency and severity. The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, which produced a record 30 named storms, may foreshadow future hurricane activity. The high winds, immense rainfall, and flooding associated with Hurricane Harvey in 2017 and Hurricane Florence in 2018 will likely become more common and damaging as the ocean heats up.

Weather patterns are changing due to warmer ocean temperatures because the ocean is key to the movement of water around the globe. Due to its enormous size, the ocean helps power weather by driving the planet’s evaporation and precipitation cycles.

Higher sea surface temperatures increase evaporation and add additional moisture to the atmosphere over the oceans. This extra water vapor boosts the precipitation dumped by rainstorms and blizzards on coastal areas and inland locations.

While wetter areas will experience more precipitation, dry regions of the world will likely become drier due to the changes ocean warming causes to the water cycle. These arid conditions will cause areas like the southwestern United States to experience prolonged droughts and increased wildfire risks.

There may also be a link between warming Arctic waters and the polar vortex—icy blasts of cold air—over the United States and Europe. Scientists are examining whether the lack of sea ice due to warmer ocean temperatures weakens the jet stream, which usually keeps Arctic air in check and enables that air to plunge south instead.

How does ocean warming threaten marine life?

The majority of ocean life thrives in the ocean’s surface layer, the part that’s warming the fastest. Sensitive to even tiny temperature changes, marine organisms are quickly trying to adapt to a hotter ocean. Three threats may fundamentally change the sea and the life within it: ocean acidification, coral bleaching, and marine heatwaves.

Spurred by ocean warming, these hazards are altering critical ocean systems from primary productivity to the distribution of species. The impacts on fisheries and aquaculture threaten food security for millions and the global economies that depend on them.

Ocean Acidification

Coastal ocean acidification sets off a chain of chemical reactions that lowers the ocean’s pH, making it more acidic. Acidification can affect many marine organisms, especially those that build their shells from calcium carbonate such as the scallops shown here. (Photo by Erin Koenig, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution).

Roughly one-third of the carbon dioxide pumped into the atmosphere by human activities is absorbed by the ocean. While this process offsets some climate impacts, when carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater, it forms carbonic acid and decreases the pH of the water. Known as ocean acidification, this fundamental change in ocean chemistry makes it harder for calcifying organisms such as corals, shellfish, and some plankton (the base of the marine food web) to grow, reproduce, and create their protective shells and skeletons. The pH of the ocean is now around 8.1, representing a 25 percent increase in acidity. As the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continues to climb, seawater acidity could drop to 7.8 by 2100. Ongoing ocean acidification will threaten vital ocean habitats and people who depend on fishing and aquaculture for food and income. See related topic on Ocean Acidification »

Coral Bleaching

Reef-building corals contain algae cells in their tissues that nourish them and give them their distinctive color. High water temperatures cause corals to release their algae and lose their color, a condition known as "bleaching" seen here in a 2010 bleaching event in the Red Sea. (Photo by Konrad Hughen © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The world’s coral reefs sustain such massive, diverse amounts of marine life that they’re home to 25 percent of all fish in the sea. Reefs support local economies by sustaining fisheries, protecting coastlines from storm surges and flooding, and supporting tourism. Corals are also susceptible to subtle temperature changes in the sea. A reef is a colony of animals that host microscopic algae in their tissues; these vibrant creatures provide corals their food and color. Even warming of 2–3°F can transform a reef. Heat stresses corals, causing them to eject the algae and lose their color, hence the term coral bleaching. Corals can recover from a bleaching event if the water cools within a few weeks, but more often, bleaching causes corals to starve and die. Mass coral bleaching was first noticed on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef in the early 1980s. Major bleaching events have since happened with growing frequency to reefs throughout the South Pacific and the tropical Atlantic as ocean temperatures spike. Some corals can recover, and other species are proving resistant to bleaching, but many don’t bounce back. Scientists estimate the global ocean could lose 70 to 90 percent of coral reefs by 2045 due to bleaching and other warming impacts. Related: Why do corals bleach?

Marine Heatwaves

Climate change causes dangerous heat waves over land and also in the sea. Marine heatwaves are prolonged periods of warmer than usual ocean temperature anomalies, which can cause harmful algal blooms, coral bleaching, and mass die-offs of fish, seabirds, and other organisms. Marine heatwaves have devastated commercial fisheries in the Pacific Ocean by forcing fish to migrate to cooler waters and wreaked havoc on the Great Barrier Reef in recent years by driving mass coral bleaching events.

Marine heatwaves are a new area of study. Scientists think marine heatwaves are not a recent phenomenon but that their frequency, intensity, and duration are changing as the ocean warms. Marine heatwaves could occur more often in the 21st century as the ocean absorbs more heat from the atmosphere.

What are scientists doing to understand ocean warming?

The impacts of ocean warming will likely intensify in the coming decades. Carbon dioxide stays in the atmosphere for thousands of years, meaning that even if carbon dioxide emissions cease today, the effects of ocean warming will linger for just as long.

More research is needed to understand how the ocean is warming and what the effects of this warming will be. For example, WHOI scientists are examining the links between marine heatwaves and ocean processes to better predict the impact of extreme heat on ocean ecosystems.

LEARN MORE: Studies investigate marine heatwaves, shifting ocean currents

Another team of WHOI researchers led a study that identifies how ocean acidification affects coral skeletons. Their work will allow scientists to more precisely predict how and where corals will be most vulnerable to acidifying seawater.

LEARN MORE: Scientists Pinpoint How Ocean Acidification Weakens Coral Skeletons

From extreme weather to marine heatwaves, the effects of ocean warming jeopardize property, lives, and livelihoods in coastal and inland areas worldwide. But there’s a reason for hope. Continued research on ocean warming will enable societies to confront the myriad risks associated with hotter seas, including fisheries impacts, sea level rise, and extreme weather.

Buis, Alan. How Climate Change May Be Impacting Storms Over Earth's Tropical Oceans. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. https://climate.nasa.gov/blog/2956/how-climate-change-may-be-impacting-storms-over-earths-tropical-oceans/. March 10, 2020.

Dahlman, LuAnn, et. al. Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content. NOAA: Climate.gov. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-ocean-heat-content. Accessed on February 20, 2020.

IPCC. Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5°C. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/. Accessed on February 20, 2020.

IPCC. Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/. Accessed on February 18, 2021.

Johnson, G.C., Lyman, J.M. Warming trends increasingly dominate global ocean. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 757–761. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0822-0

Laufkötter, C., et. al. High-impact marine heatwaves attributable to human-induced global warming. Science, vol. 369, Issue 6511. doi: 10.1126/science.aba0690

Lindsey, Rebecca. No safe haven for coral from the combined impacts of warming and ocean acidification. NOAA: Climate.gov. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/featured-images/no-safe-haven-coral-combined-impacts-warming-and-ocean-acidification. November 13, 2018.

Oliver, E.C.J., et al. Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat Commun, 9, 1324. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03732-9