Fish swimming around a coral reef in the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA), one of the world's largest marine conservation reserves. Photo by Jim Stringer

What are reef fishes?

Corals may form the base of coral reef systems, but they’re just some of the thousands of species inhabiting any given reef. From cryptic crabs and snapping shrimp to sea stars and urchins, all kinds of animals hide among the nooks and crannies of a coral reef. Perhaps most obvious to the casual observer are the colorful fishes that flit about, their bright scales reflecting sunlight as they move through these shallow waters.

Reef fishes (fishes indicates multiple species; fish is used for many individuals of the same type) include any species that spend time on the reef. Some may be relatively sedentary, spending their adult lives on a small part of the reef. Clownfish, for example, remain in close proximity to the anemones where they make their homes in a mutualistic relationship that provides food and protection for both animals. Other fish are mobile, moving along the reef or from one reef to another.

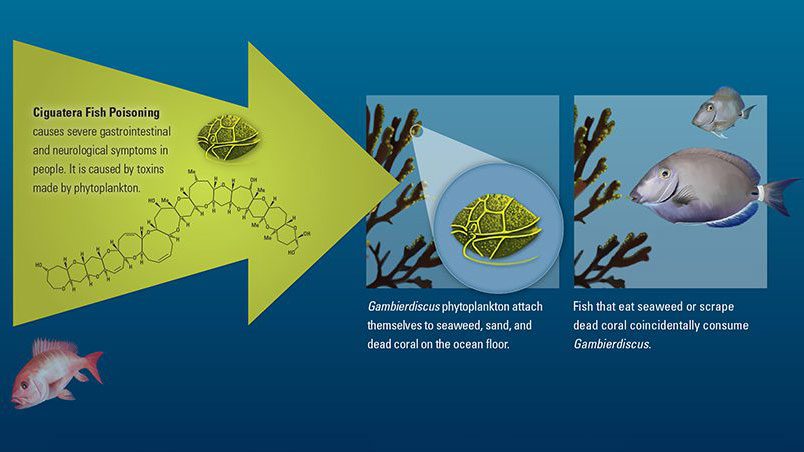

Fishes populating coral reefs vary greatly in size and what they eat, with some munching corals, others grazing algae, and others picking parasites from fish. Still others are carnivores, consuming invertebrates or other fish in a food chain that ends with top predators, like sharks and humans.

Why are reef fishes important?

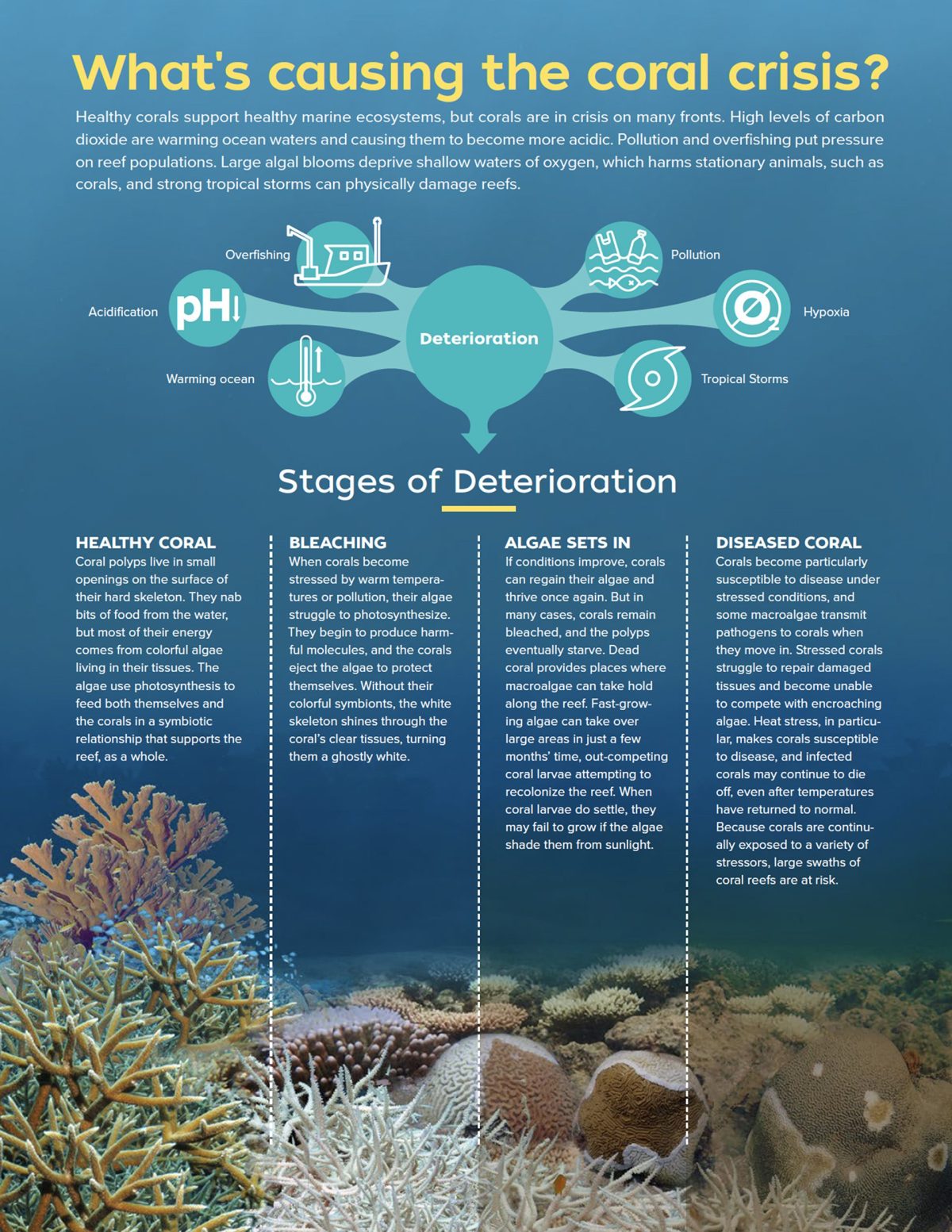

The fishes that inhabit a coral reef play essential roles in the reef ecosystem, and recent research has shown that reefs without fish struggle to recover from bleaching or other events that damage the coral. When corals die from bleaching, pollution, infection, or some other cause, herbivorous fishes play a critical role in nursing the reef back to health. They do this by scouring the reef for macroalgae—large, plant-like forms of algae that anchor on dead coral and subsequently crowd out recovering or newly established corals. Herbivorous fishes, such as parrotfishes, surgeonfishes, and rabbitfishes, mow down these interlopers, thereby allowing corals to rebound.

Corallivorous fishes eat coral, which may seem like a problem for struggling coral reefs, but despite the damage they can do, they also provide an essential service. Many butterflyfishes and parrotfishes nibble on coral polyps. In the process, they sometimes scrape off pieces of the underlying skeleton, and some, such as the bumphead parrotfish, are anything but delicate, biting large chunks from the corals. The fish’s digestive system grinds up the pieces of skeleton, which are later deposited on the reef substrate as sand. Such behavior reshapes the reef, flattening knobs of new growth and keeping fast-growing corals under control. On reefs where a few coral species dominate, this behavior can increase the diversity of corals—and therefore the diversity of organisms that rely upon those corals.

Fishes that consume zooplankton play an essential role in providing reefs with nutrients. Planktivores, such as cardinalfishes and damselfishes, feed in the water column, sometimes in areas far from the reef. They fill up on plankton that drift by on ocean currents or other small invertebrates that rest on the reef during the day and rise into the water column at night. When the fish return to the reef to rest—and many return to the same areas night after night—they deposit nutrients onto the reef in solid form that is unlikely to drift away. This provides essential carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous for the reef and acts as a critical link in the ocean-reef food web.

A highly specialized group is the parasite pickers, small fishes such as cleaner wrasse that remove dead skin, scales, and parasites from larger fishes that stop by “cleaning stations” along the reef. Cleaners improve the health of other fishes, and their presence has been linked to settlement of larval fishes on the reef. Larger fishes visiting a cleaning station remain still, even opening their mouths to allow the tiny wrasses inside for a thorough cleaning of the gills. Although cleaner fishes play an important role in reef health, some also steal a meal by taking bites of mucus or living tissue from their “clients.”

Many fishes eat other fish, whether these are smaller herbivores, corallivores, planktivores, or other piscivores. Some species, such as frogfishes, lionfishes, and scorpionfishes, lie hidden on the reef or sandy bottom, waiting for unsuspecting fish to swim close enough to nab. Others, such as jacks and sharks, pursue their prey through the water. Researchers have found that top-level predators, such as sharks, help to control populations of mid-level piscivores that otherwise decimate populations of herbivorous fishes and invertebrates. Loss of herbivores allows macroalgae to grow unchecked, leading to further degradation of the coral reef.

How are scientists studying reef fish?

Researchers at WHOI are working to understand how fish communities interact with each other and other organisms on coral reefs. Through the use of newly developed methods of marking larval and adult fish, they are tracking movement of fishes across broad sections of reef to understand how these animals settle into and use these areas. They are also working to understand intricate marine food webs, particularly for fish larvae and small fishes, to understand how they link plankton to species higher in the food chain.

Cole, A.J. et al. Diversity and functional importance of coral-feeding fish on tropical coral reefs. Fish and Fisheries, vol. 9. 2008. doi: 10.1111/j/1467-2979.2008.00290.x.

Eckes, M. et al. Fish mucus versus parasitic gnathiid isopods as sources of energy and sunscreens for a cleaner fish. Coral Reefs, vol. 34. 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00338-015-1313-z.

Emslie, M.J., et al. The distribution of planktivorous damselfishes (Pomacentridae) on the Great Barrier Reef and the relative influences of habitat and predation. Diversity, vol. 11. 2019. doi: 10.3390/d11030033.

Fisheries Oceanography and Larval Fish Ecology Lab, WHOI. https://www.whoi.edu/science/B/FOLFElab/FOLFE_Lab_at_WHOI/Research.html

Gray, A.E. A fish that shapes the reef. NOAA. April 27, 2017. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/science-blog/fish-shapes-reef

Green, A.L. & D.R. Bellwood. Monitoring functional groups of herbivorous reef fishes as indicators of coral reef resilience. IUCN. August 20, 2009. https://www.iucn.org/content/monitoring-functional-groups-herbivorous-reef-fishes-indicators-coral-reef-resilience

Marnane, M.J. & D.R. Bellwood. Diet and nocturnal foraging in cardinalfishes (Apogonidae) at One Tree Reef, Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Marine Ecology Progress Series, vol. 231. April 2002. doi: 10.3354/meps231261.

Mihalitsis, M. & D.R. Bellwood. Morphological and functional diversity of piscivorous fishes on coral reefs. Coral Reefs, vol. 38. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s00338-019-01820-w.

National Marine Sanctuary Foundation. Sea anemone and clownfish: Behind the scenes of an iconic friendship. October 5, 2020. https://marinesanctuary.org/blog/sea-anemone-and-clownfish-behind-the-scenes-of-an-iconic-friendship/

Ruppert, J.L.W., et al. Caught in the middle: combined impacts of shark removal and coral loss on the fish communities of coral reefs. PLOS One, vol. 8. 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074648.

Sun, D. et al. Presence of cleaner wrasse increases the recruitment of damselfishes to coral reefs. Biology Letters, vol. 11. 2015. doi: 10.108/rsbl.2015.0456.

The Fish Ecology Lab, WHOI. https://simonthorrold.com/research/