Emperor penguins have unusual nesting habits. Large numbers of penguins arrive in Antarctica in March or April to start looking for a mate. That may not sound unusual, but in Antarctica, that’s the end of summer and start of a long, dark winter. Some birds are looking for a new mate. Others are reuniting with their mate from previous years. The process involves lots of waddling, singing, and head bobbing.

After mating, the female lays a single egg. There isn’t nesting material in Antarctica, so she lays it directly on the ice. It doesn’t stay there long. Her mate rolls it onto his feet and covers it with his belly to keep it warm. Meanwhile, the female, who hasn’t eaten in two months, returns to the ice-cold ocean to feed. The males huddle together in the long Antarctic night, incubating the eggs as southern lights dance across the sky. They will get to eat after the eggs hatch in July.

Emperor penguins don’t eat when they’re on land. They feast on seafood: krill, squid, and fish. These foods are abundant in the cold Antarctic waters. But in winter, open water can be many kilometers away from where the penguins gather in their breeding colonies. When females—and later, males—return to the ocean to feed, they need a spot that gives them easy access to both the water and the ice. After all, birds can’t breathe underwater. They need places where they can come up for air and haul out onto the ice to return to the colony.

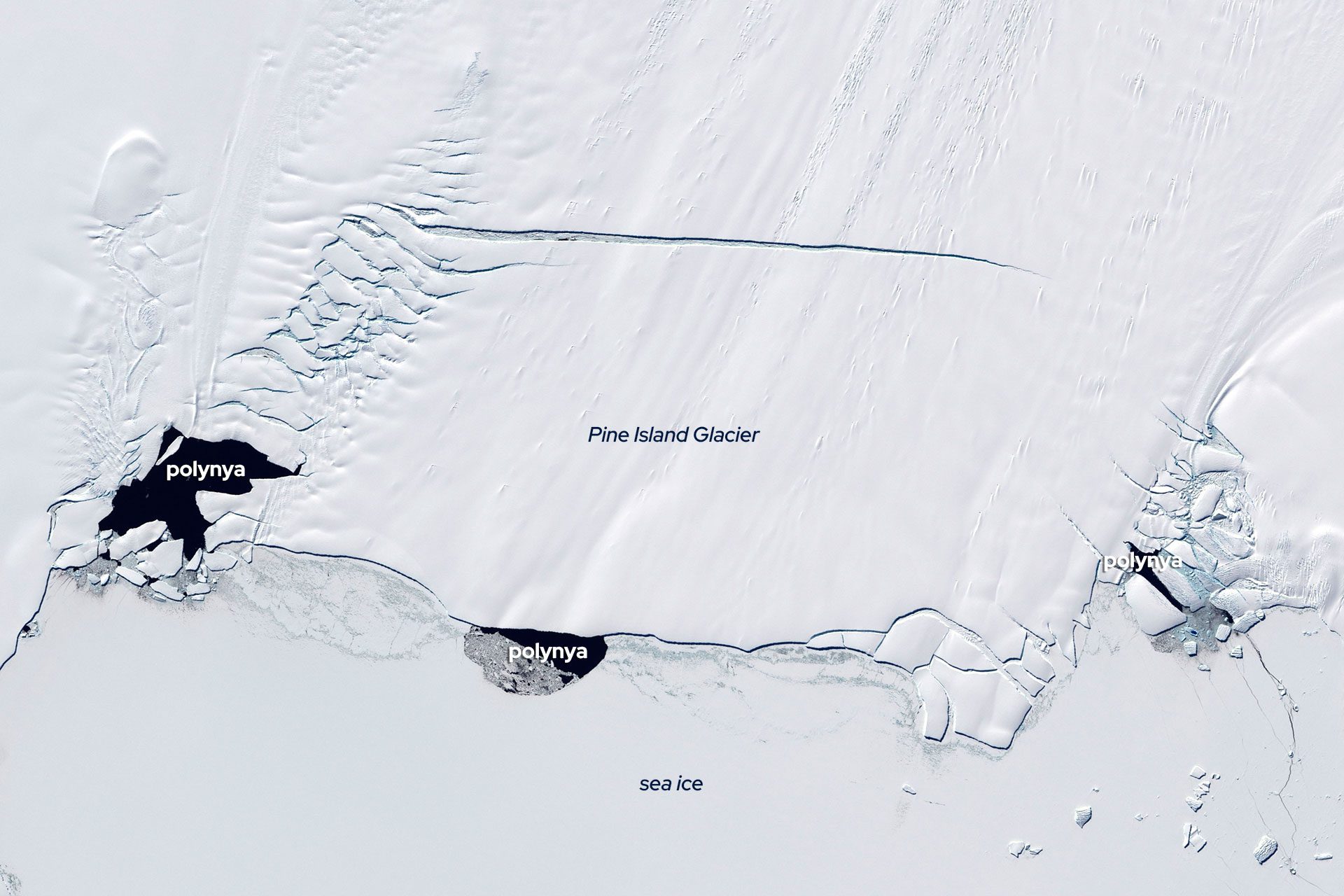

They also need places that are teeming with fish and other types of prey. Winter winds create just such openings in the ice. Called polynyas (puh-LIN-yuhs), these openings are created when strong winds blow from the Antarctic continent out over the ocean. All around the coastline, wind pushes ice away from shore, exposing pockets of water to the air. That causes new ice to form, which is also pushed away.

It’s these openings that draw in lots of marine life. Diatoms and tiny algae grow in these spaces during sunny summer months. That attracts tiny zooplankton, which in turn attracts krill. Krill are a favorite food of all kinds of marine animals, from fish to whales. Soon the polynya is home to an entire community of animals, even after the sun dips below the horizon for the winter. That makes for a feast for the penguins. Adults rebuild their energy reserves after breeding, then take turns bringing food to their chick. It’s not easy raising a chick in the Antarctic winter, but polynyas make it possible.

Some polynyas happen in the same place each winter. Others don’t last very long, and it’s these short-term polynyas that emperor penguins seem to use. The reason may have to do with mixing of the water. In areas where polynyas persist, winter winds continually mix upper layers of water with lower ones. Freezing of new ice also makes the water saltier in these areas, which contributes to mixing. Mixing can send plankton deep into the water column—too deep to survive. With less food to eat, fewer krill and other small predators gather. So, penguins may go for the short-lived, food-rich ones that are also closer to their home colony.

LEARN MORE

Emperor Penguins

The emperor penguin is the largest living penguin species standing around 115 centimeters tall. Once they have found a partner, they work together to keep their young fed and safe.

Australian Antarctic Program. Emperor Penguin Breeding Cycle. https://www.antarctica.gov.au/about-antarctica/animals/penguins/emperor-penguin/breeding-cycle/

Labrousse, S. et al. Dynamic find-scale sea icescape shapes adult emperor penguin foragign habitat in East Antarctica. Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 11. 2019. doi:10.1029/2019GL084347

Santora, J.A. et al. Geographic structuring of Antarctic penguin populations. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2020. doi: 10.1111/geb.13144.

Schmidt, L.J. Polynyas, CO2, and Diatoms in the Southern Ocean. NASA Earth Observatory. August 7, 2000. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/Polynyas

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Open water Oasis in Antarctica. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2_7wQGrRqjg

DIVE INTO MORE OCEAN FACTS

Can AI help us explore the ocean?

Learn how scientists at WHOI are using AI, like the software “Spock,” to enable autonomous underwater robots, such as Nereid Under Ice and CUREE, to study marine life and explore ocean environments.

What makes the ocean salty?

The water flowing into the ocean comes from freshwater streams and rivers. These bodies of water do contain salt. It dissolves from rocks on land. That’s because rain is slightly acidic.

What’s the difference between climate and weather?

We often hear about the weather. We also hear about climate. The two terms are related. But they are not the same thing. What’s the difference?

What causes ocean waves?

A trip to the ocean means sun, wind, and waves. Surfers ride them. Children play in them. Swimmers dive beneath them. But what causes waves?