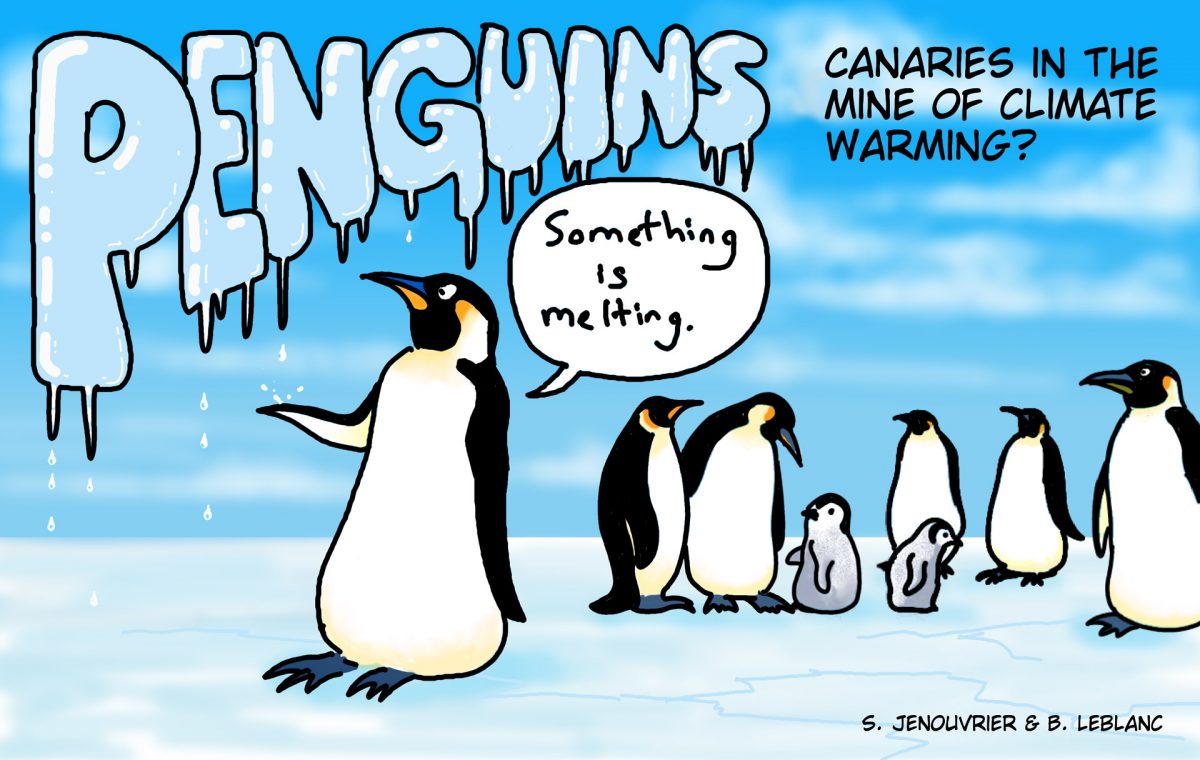

NEW: Emperor penguins granted protections under Endangered Species Act

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has announced that emperor penguins have been listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) based on evidence that the animal's sea ice habitat is shrinking and is likely to continue to do so over the next several decades. The ESA is the world’s strongest environmental law focused on preventing extinction and facilitating recovery of imperiled species and has increasingly been applied to provide protection for species threatened primarily, or in part, by climate change, with the polar bear being the first species listed principally due to global warming (2008). Decades of studies by an international team of penguin researchers, including Stephanie Jenouvrier, associate scientist, and seabird ecologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, were instrumental in establishing the need for protections and highlighting that urgent climate action is needed to protect the species. Emperor penguins will be pushed towards extinction by the climate crisis melting the sea ice they need for survival and reproduction. Research from penguin scientists is key to informing policy around much-needed protections for the emperor penguin. Although they are found in Antarctica, far from human civilization, emperor penguins live in such delicate balance with their rapidly changing environment.

What are emperor penguins?

Penguins are a group of aquatic, flightless birds. Almost all penguins live in the Southern Hemisphere and are highly adapted to life in the water. The emperor is the largest living penguin species standing around 115 centimeters tall. Once they have found a partner, they work together to keep their young fed and safe.

Emperor penguins breed and molt on sea ice and chunks of frozen seawater. Of the 18 different species of penguins, only two (the emperor and Adélie) are actually true Antarctic residents.

They lay either one at a time and take several months to raise their chicks. The females leave the colony to catch fish and fatten up so they can feed their chicks. The males stay behind and cradle the egg on the tops of their feet, tucked under their brooding pouch for warmth and protection. Too little sea ice during this time can reduce the availability of breeding sites and prey; too much sea ice means longer hunting trips for adults, which in turn means lower feeding rates for chicks. They can also dive at incredible depths – one study recorded a female of emperor penguin that dove 535 meters (1,755 feet) near McMurdo Sound off of Antarctica.

Most penguins feed on krill, fish, and squid, caught while swimming underwater. The emperor penguin is the only species to breed during the harsh Antarctic winter, on sea ice.

Why are they important?

Emperor penguins are a key indicator species of climate and ocean change. Their presence reflects the impact of environmental variability over large scales in the global ocean.

Chicks hatch into one of Earth’s most inhospitable places. Their colonies are on the sea ice and they even breed on frozen sea. The species plays a vital part of the Antarctic food chain – they eat small ocean creatures, and are an important source of food for predators like leopard seals and killer whales.

Emperor penguins are extremely vulnerable to a warming climate. They are well adapted to thrive in freezing conditions, but in parts of the Antarctic Peninsula, sea ice cover has reduced by over 60% in 30 years and one colony has virtually disappeared.

What are the threats, and what are scientists doing to protect emperor penguins?

Emperor penguins are being pushed towards extinction by the climate crisis which is melting the sea ice they need for survival and reproduction. These iconic birds need sea ice for breeding and raising their chicks. In parts of Antarctica where sea ice is disappearing or breaking up early, their populations are declining or have been lost entirely.

New research suggests that by 2100, under emissions scenarios resulting from current energy-system trends and policies, emperor penguins will be in danger of extinction throughout its entire range.

Climate models project significant declines in Antarctic sea ice to which the emperor penguins’ life cycle is closely tied. Current studies on the species reinforce the need for legal recognition and enhanced precautionary management, particularly given continued increases in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. According to the International Paris Agreement, a 2015 landmark decision to combat climate change and to accelerate and intensify the actions and investments needed for a sustainable low carbon future, rapid cuts in GHG are by far the most important action for preventing catastrophic species losses.

ECHO robot monitors penguin health

WHOI researchers are testing the use of robots to study and access the vulnerability of marine ecosystems, including Emperor penguins, which are a sentinel species to climate change. ECHO is the name of the approximately two-foot tall autonomous and remote controlled unmanned ground vehicle (UGV) being tested for the first time in Antarctica. The robot, used as a mobile Radio-Frequency Identification (RFID) antenna, works in conjunction with an existing photographic penguin observatory to optimize and automate the data retrieval process. Mounted with wireless data-receivers, the ECHO UGV will automatically retrieve oceanographic data from equipped birds. It is part of the MARS project to measure the health of the Antarctic marine ecosystems through long-term monitoring of the emperor penguin populations over the next 30 years, and part of a larger international effort with funding from NSF.