Photo by Cory Mendenhall, U.S. Coast Guard

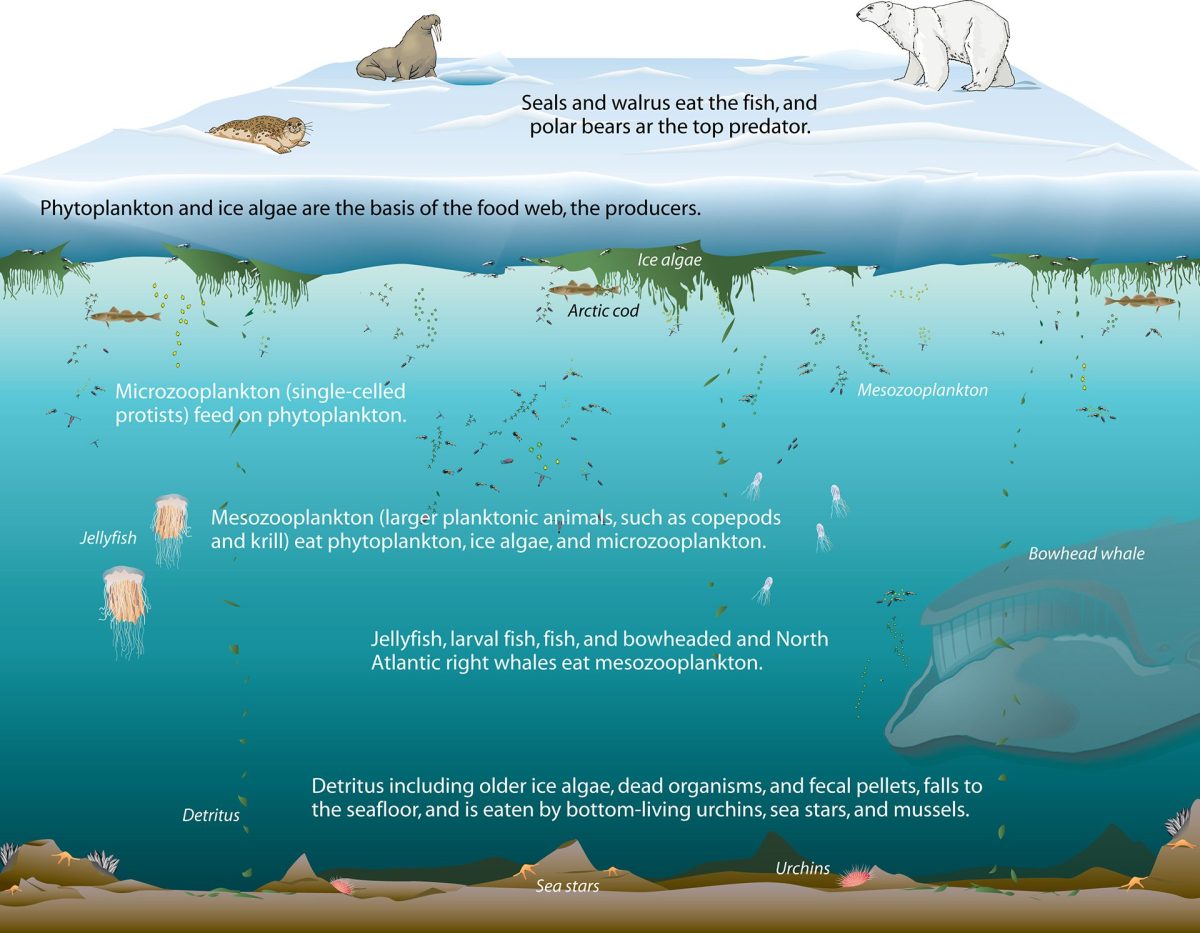

Arctic Ocean Ecosystem

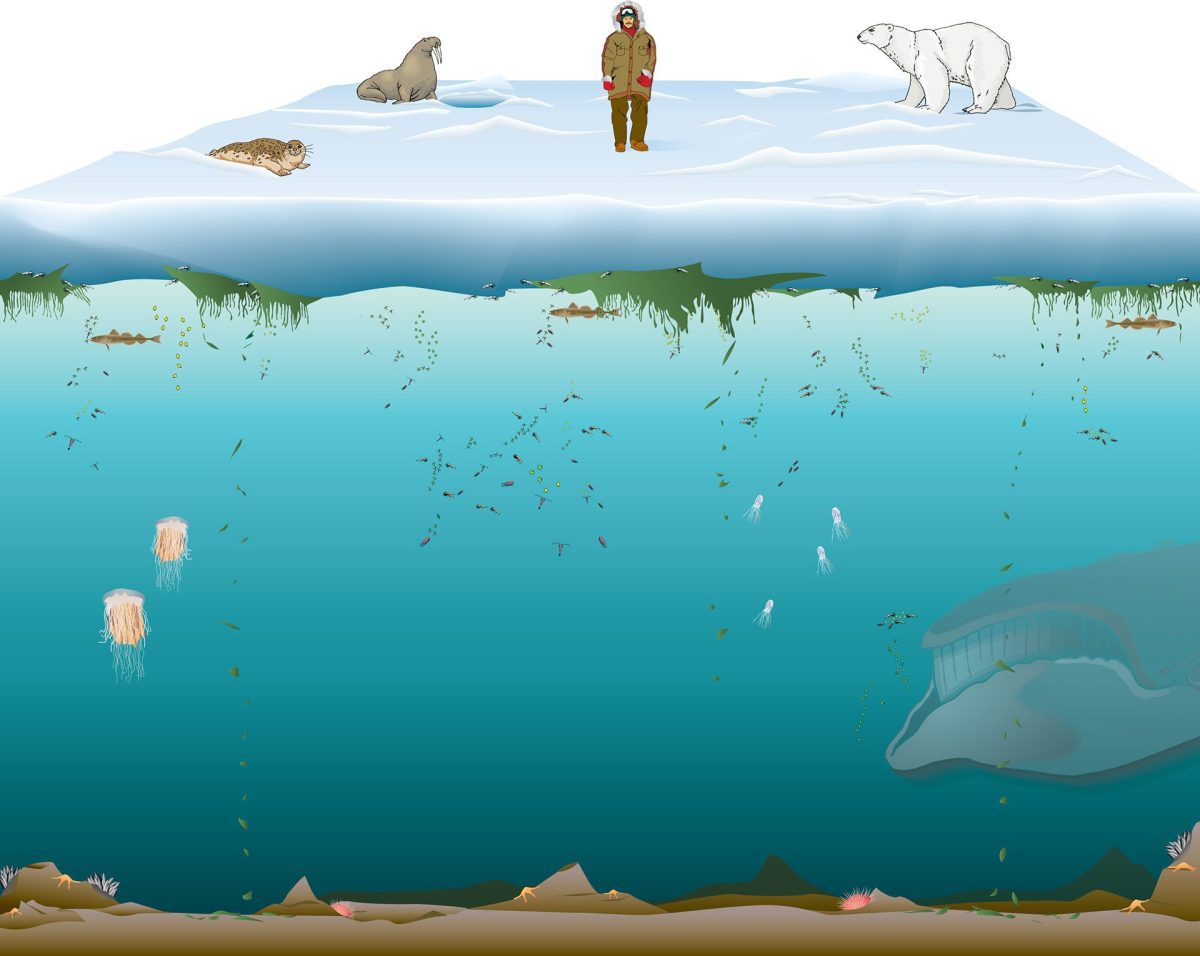

The Arctic Ocean is one of the planet's most remote and formidable large ocean basins. Much of it is permanently covered by shifting sea ice. Half the year it is plunged into total darkness and it is buffeted by bitterly cold winds year-round. Despite this, life thrives in the far north, enduring some of the greatest extremes in light and temperature on the planet.

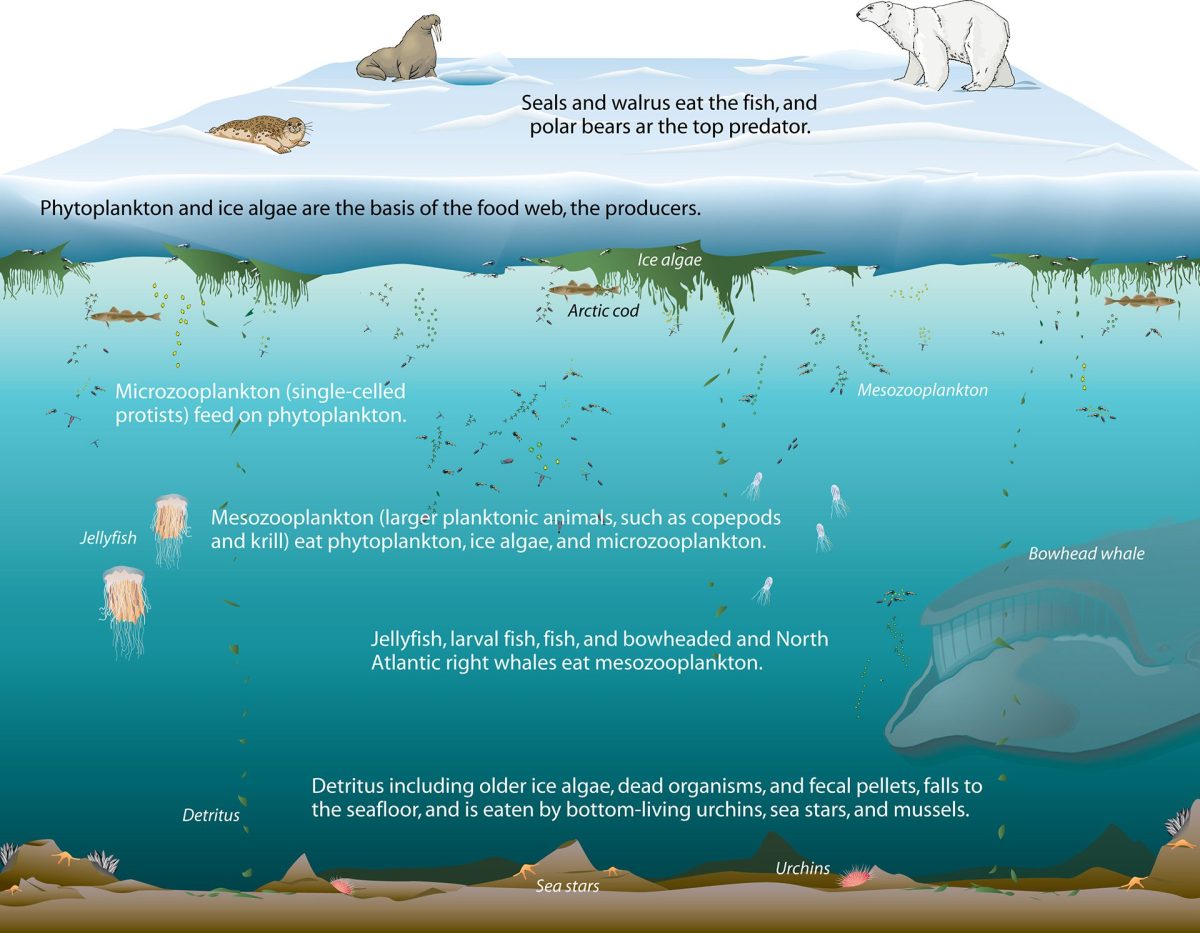

Polar bears roam the Arctic ice while pods of orcas hunt beneath the ocean surface. Supporting these top predators is a complex ecosystem that includes a wide variety of fish, birds, mammals, and other organisms. At the base of this web, supporting this surprising abundance of life, are the microscopic phytoplankton and algae that produce organic material using the sun's energy.

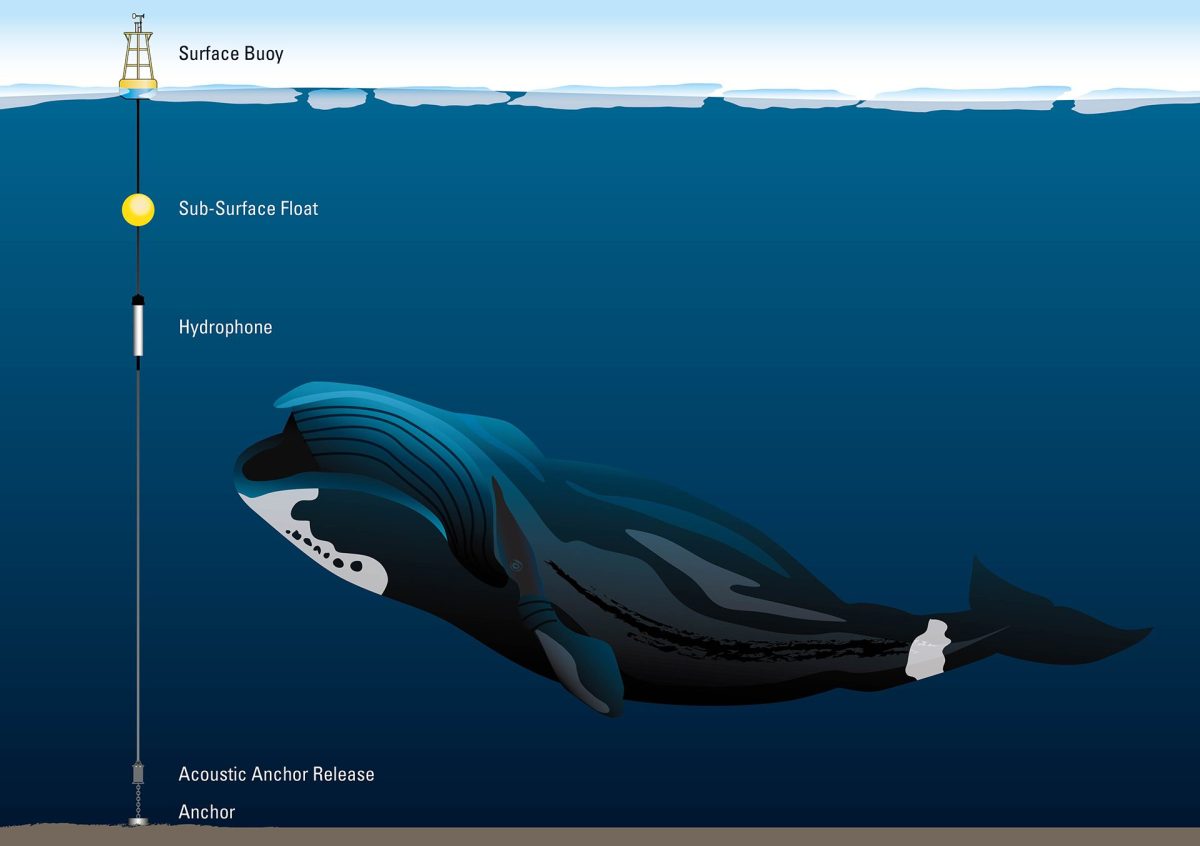

The Arctic’s extreme environmental conditions have limited efforts to study this complex food web. Expeditions to the remote Arctic are difficult and expensive. When scientists can get there at all, it is usually only in summer. Such gaps in our observations have limited understanding of the Arctic ecosystem's intricacies and vulnerabilities—at a time when that system appears to be increasingly vulnerable.

Scientists know that warming temperatures are affecting the Arctic Ocean in countless ways, producing changes that may have cascading effects on the Arctic’s interlinked and delicately balanced ecosystem. Documented declines in Arctic sea ice is reducing the habitat for bacteria, viruses, unicellular algae, diatoms, ice worms and small crustaceans that live inside the ice. As the ice warms in spring and summer, these tiny organisms are released into the surface water, where they become food for a wide range of fish and shrimp, which in turn become food for larger animals.

Changes in the food web not only threaten life in the Arctic region, they also could have impacts on Earth’s climate. In addition to providing the base of the food web in the far north, populations of Arctic plankton also convert carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into organic matter that eventually sinks to the ocean bottom—effectively extracting a heat-trapping greenhouse gas from the atmosphere.

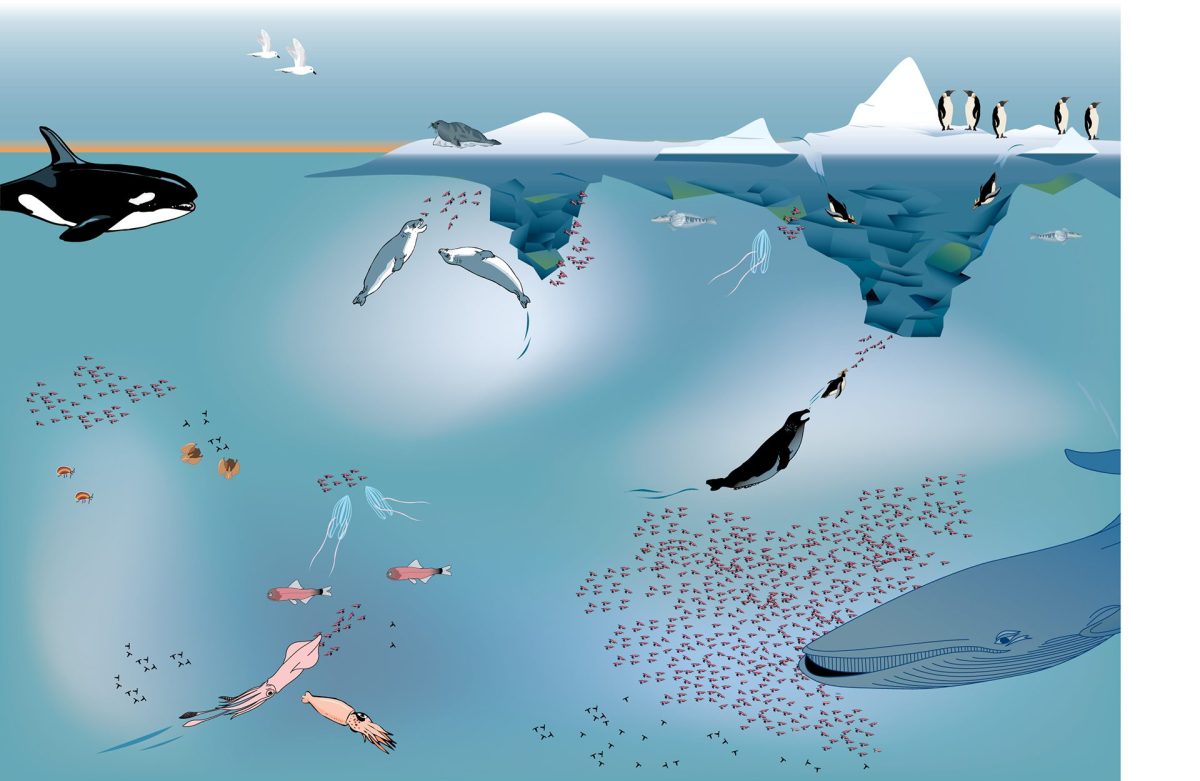

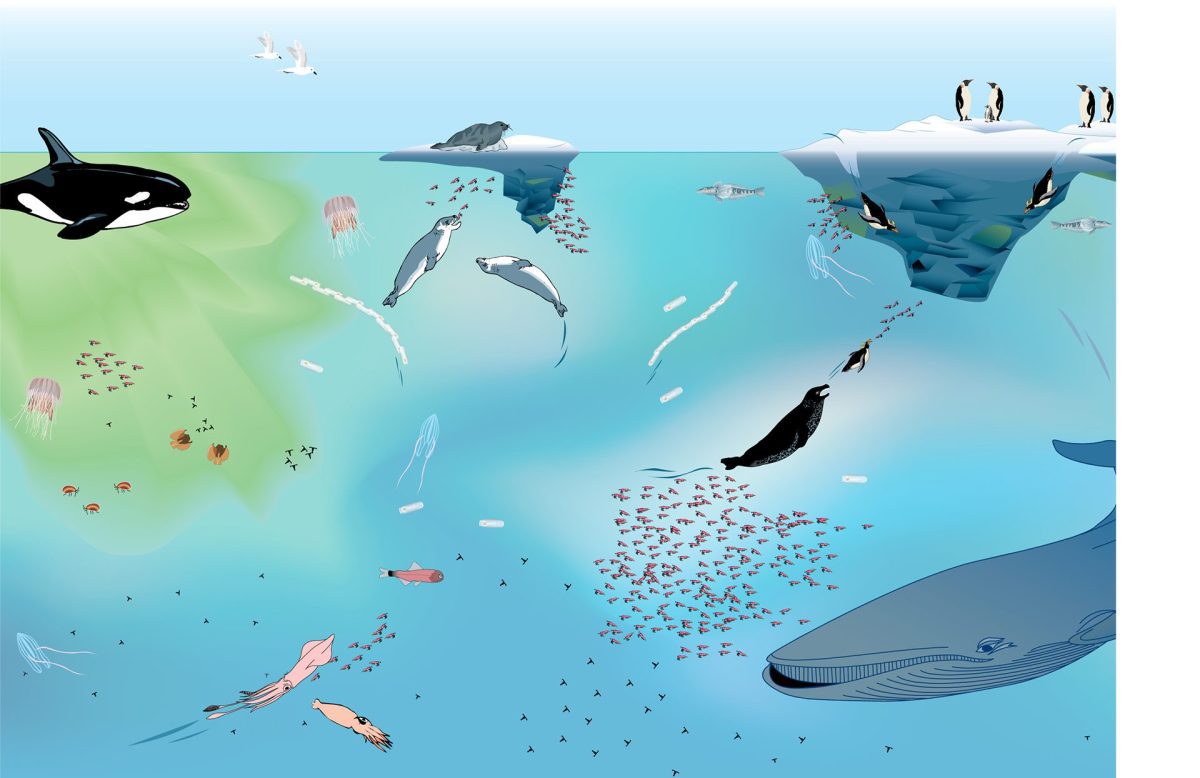

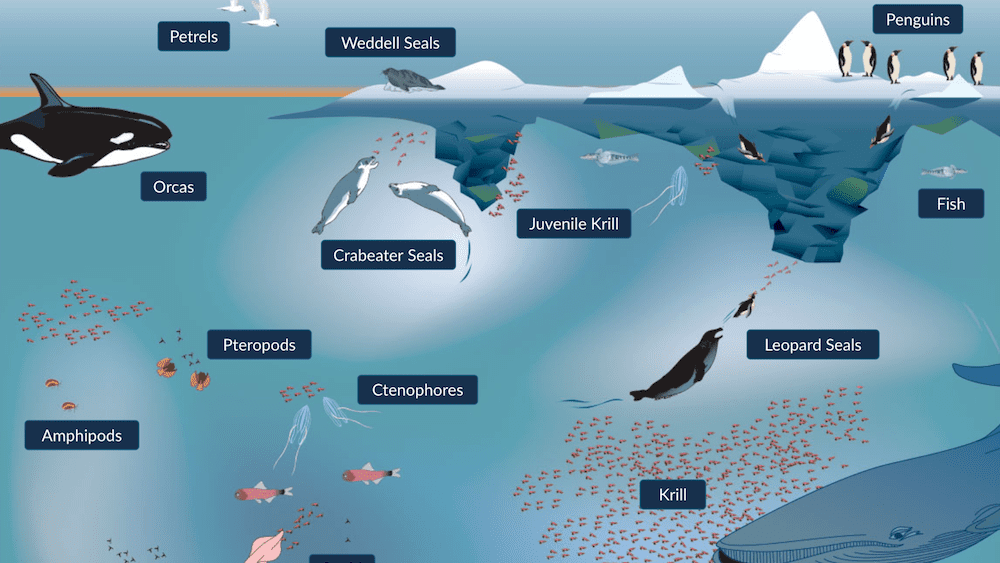

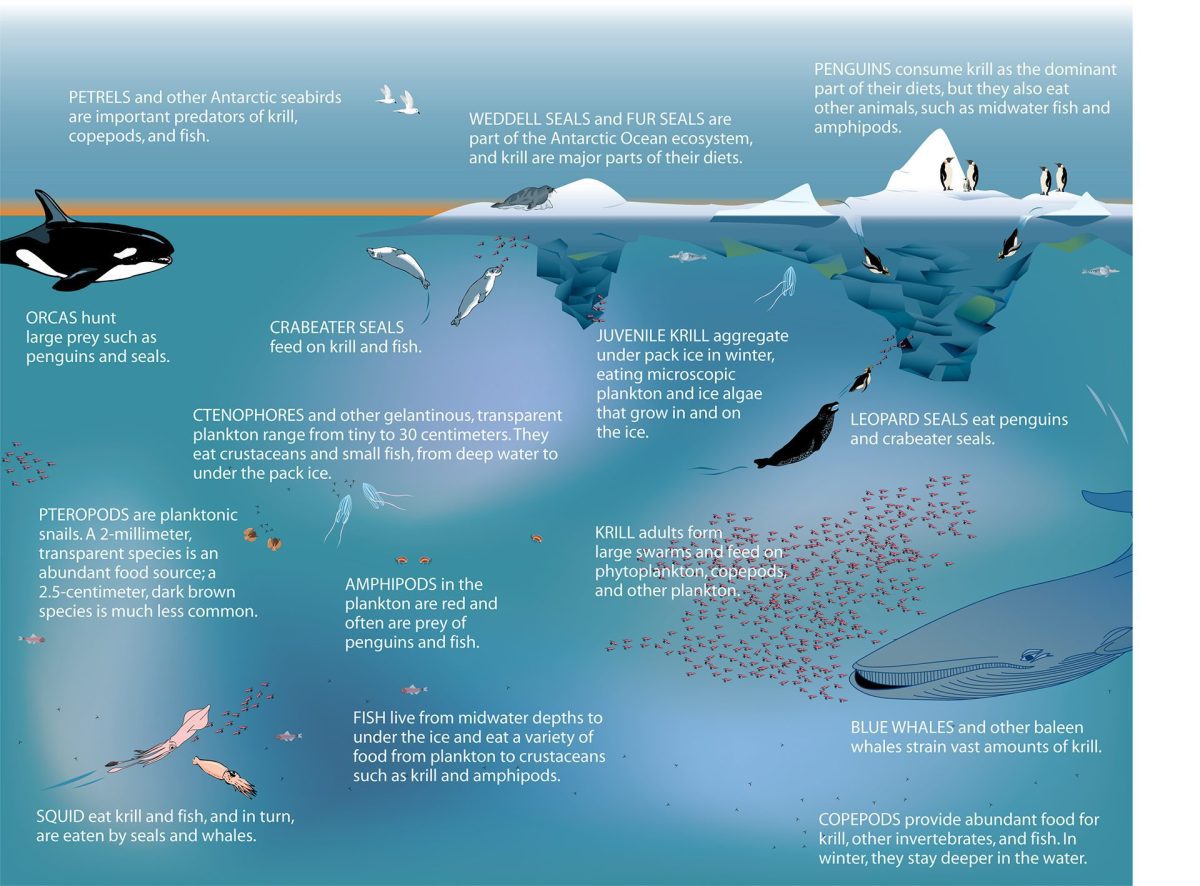

Much of the ocean around Antarctica is ice-covered for half the year, and the temperature is near freezing year-round. Yet, the sea here is full of life, from microscopic algae to shrimplike krill to large predators that depend on them. In fact, this is one of the most productive oceans on earth, and its cycle of life is tied to the change in seasons.

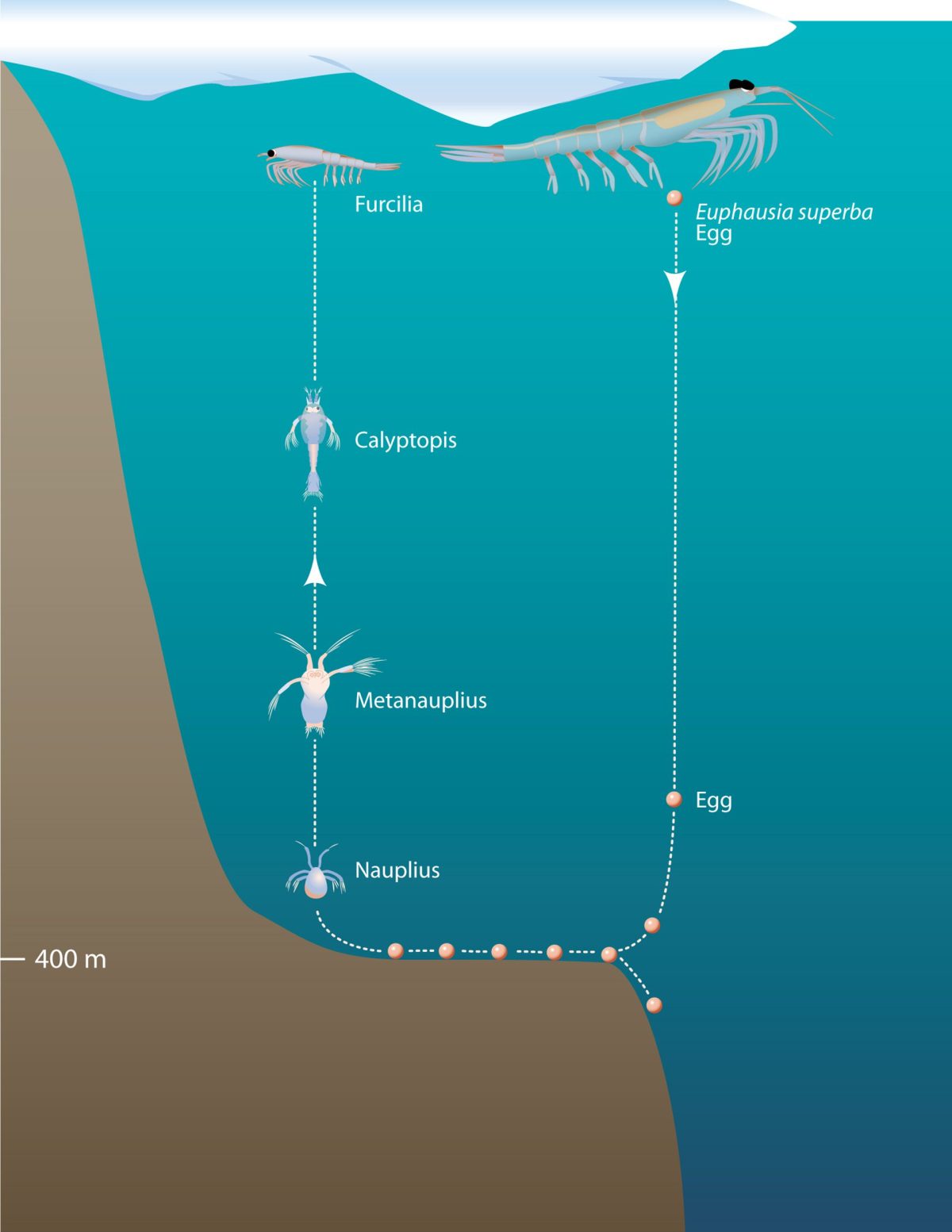

Each winter in Antarctica, as the sun disappears and temperatures plunge, ice forms on the sea and extends outward from the continent to cover large areas of ocean. The ice is important to the ecosystem, because microscopic, single-celled algae—the same kinds that drift in the open water as phytoplankton—are trapped inside the ice as it forms and also grow on the ice’s underside. Young krill congregate under the ice all winter, and the algae provides critical food for them when there is not enough light to produce food in the open water. Instead of being a hardship, winter ice lets the krill survive until spring.

In spring, the sea ice melts, releasing the trapped algae into the water. The algae—now living freely as phytoplankton—find all that they need to grow: open water, lots of nutrients (compounds like plant fertilizer, stirred up from deeper water by wind and ocean circulation), and intense sunshine.

What happens next is a bloom, or population explosion, of phytoplankton in the water. Animals, especially krill, consume this abundant food supply, and multiply to astounding levels. Scientists have estimated that the krill in the ocean around Antarctica weigh more than the entire world’s human population. The krill, which are rich in protein and fat, in turn become food for large numbers of animals further up the food chain, directly or indirectly feeding penguins, seals, and whales.

Scientists studying the Antarctic marine ecosystem now know that high productivity is largely confined to the edge of the sea ice and a few other areas, rather than occurring throughout the Southern Ocean. In addition, its high productivity may be changing, as the Antarctic climate warms and there is less sea ice to support the crucial base of the food chain there.

The polar bear is the world's largest land predator, and is found throughout the Arctic. Climate change is the main threat to polar bears today. A diminishing ice pack directly affects polar bears, as sea ice is the platform from which they hunt seals. (Photo by Chris Linder, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

All Topics on Polar Life

The Watery World of Salps

A salp is a barrel-shaped, planktic tunicate that moves by pumping water through its gelatinous body, and can be seen as a single organism or in long, stringy colonies.

The Watery World of Salps

The Watery World of Salps