A photograph of the 2004 tsunami in Ao Nang, Krabi Province, Thailand. (Public domain)

What are tsunamis?

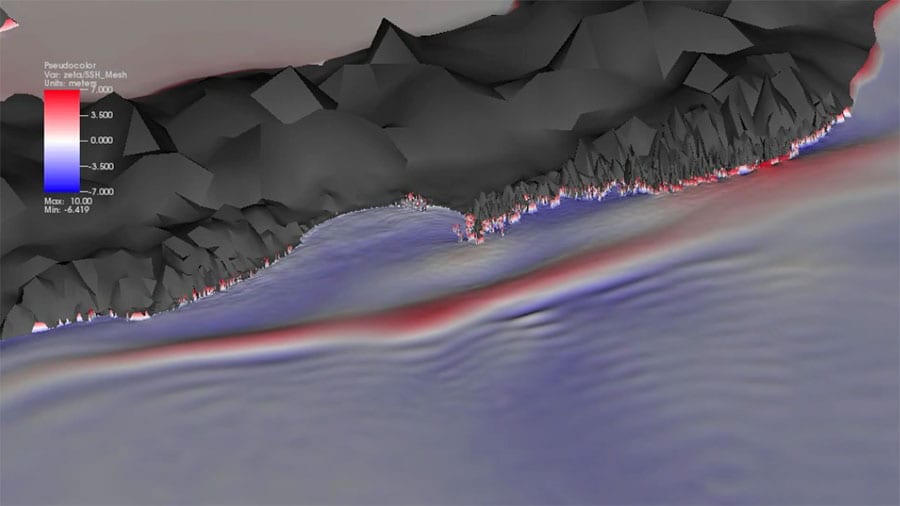

Tsunamis occur when a geologic event displaces water from seafloor to sea surface. This displacement creates a massive wave that radiates out from the point of origin. Unlike typical waves, which travel only through surface waters, tsunamis extend the full height of the water column. The deep ocean allows these waves to travel up to 800 kilometers per hour (500 miles per hour)—about the speed of a jet liner—which allows them to travel across entire ocean basins in a matter of hours. As tsunami waves enter shallower waters, they slow and grow in height, sometimes reaching 20 to 30 meters (65 to 100 feet) before they rush onto land like a wall of water, scouring everything in their path.

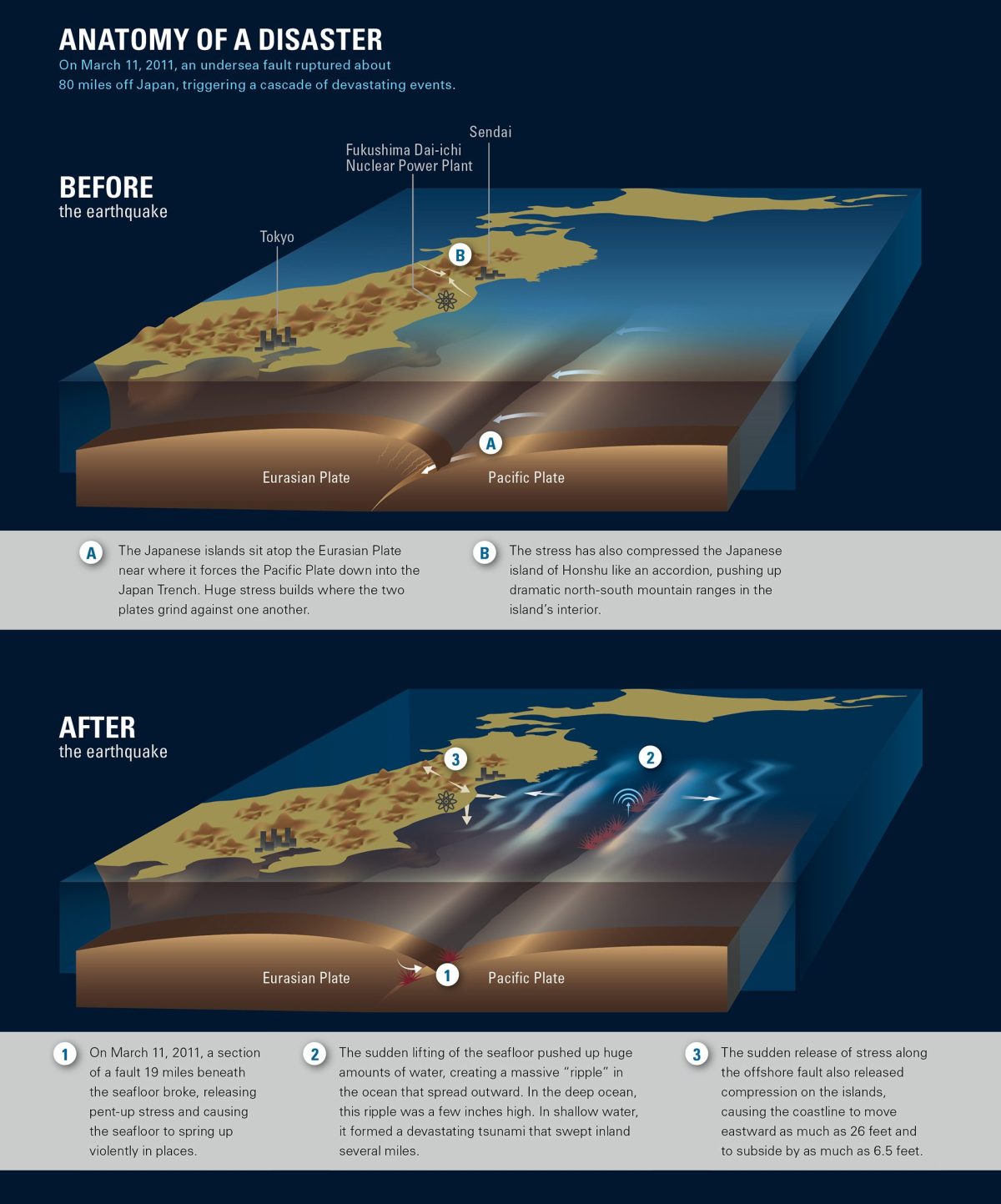

Most tsunamis are triggered by earthquakes, particularly those at subduction zones along the ocean floor. These are places where one tectonic plate pushes over the top of another. As the heavier plate sinks, it drags the leading edge of the lighter plate with it, creating a deep rift that can run for hundreds to thousands of kilometers (miles). Friction between the two plates grows over long periods of time. When the edge of the upper plate can no longer bend, it springs free with tremendous force. The movement forces the water column upwards. As the crest of water then falls, it splits into two waves that travel in opposite directions from the point of origin. As the tsunami travels, it forms additional waves, so when it reaches land, one wave after another devastates the coastline.

Other tsunami-generating events include volcanic eruptions, landslides, meteorites, and weather events, such as fast-moving storms. How far a tsunami travels depends on a variety of factors. Some impact only local shorelines, whereas others can travel around the world. The height of the wave on land is determined by a number of factors, including offshore geological features. Although people often call them tidal waves, tsunamis are not connected to tides.

Why are they important?

Tsunamis are rare but extremely dangerous events capable of causing extensive damage and loss of life. Since the mid-1800s, tsunamis have killed more than 420,000 people worldwide and caused billions of dollars in damage. Tsunamis are highly destructive; the incoming wave can pick up ships, buses, trucks, and other vehicles; derail trains; uproot trees and other vegetation; and destroy buildings, roads, and other infrastructure. People caught in the water who are lucky enough to survive can suffer severe injuries from debris.

Tsunamis can occur without warning. Some waves travel long distances, impacting shorelines far from the point of origin, where people will not have felt the earthquake or eruption that triggered the event. Sometimes people feel the earth shake but don’t realize a tsunami could follow. On December 26, 2004, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake triggered a tsunami in the Indian Ocean that ultimately affected 16 countries. People in Indonesia and Thailand felt the powerful quake but did not have a warning system and did not evacuate coastal areas. Because the fault line that triggered the tsunami lay only 150 miles off the coast of Sumatra, it took only 30 minutes for the 30-meter (100-foot) wave to reach the island, where it killed more than 100,000 people. The tsunami ultimately traveled around most of the globe. It killed nearly a quarter of a million people in total, making it the deadliest tsunami in recorded history.

Where are some of the hotspots around the planet where tsunamis form?

Most tsunamis are triggered by geologic activity associated with the Pacific Ocean’s Ring of Fire, which extends from the Chilean coast up to Alaska, across the Bering Strait, along Japan and Indonesia to New Zealand. Fault lines between the deep Pacific tectonic plate and surrounding plates have created deep ocean trenches where the plates collide. These trenches are often the source of earthquakes that trigger tsunamis. Hundreds of volcanoes also lie along the Ring of Fire. Eruptions and associated landslides can also trigger tsunamis.

How do scientists monitor them?

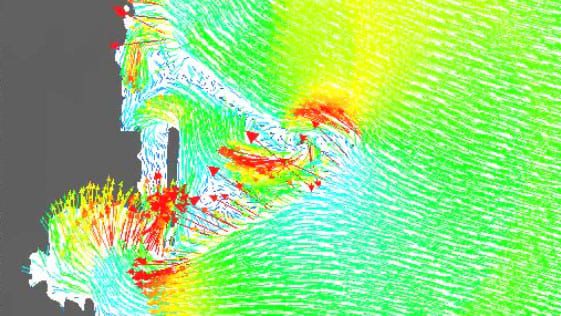

During the early 2000s, several large, deadly tsunamis prompted rapid expansion of monitoring systems. When a tsunami center detects an earthquake, researchers note the location, depth, and magnitude, all of which help determine whether a tsunami will follow. Large earthquakes (magnitude 8.5 or greater) at relatively shallow depths in the ocean floor are most likely to displace sufficient water to trigger a tsunami. Researchers feed incoming data into computer models that help determine the likely path and strength of the event, which allows them to issue warnings.

What is a tsunami warning system, and how does it work?

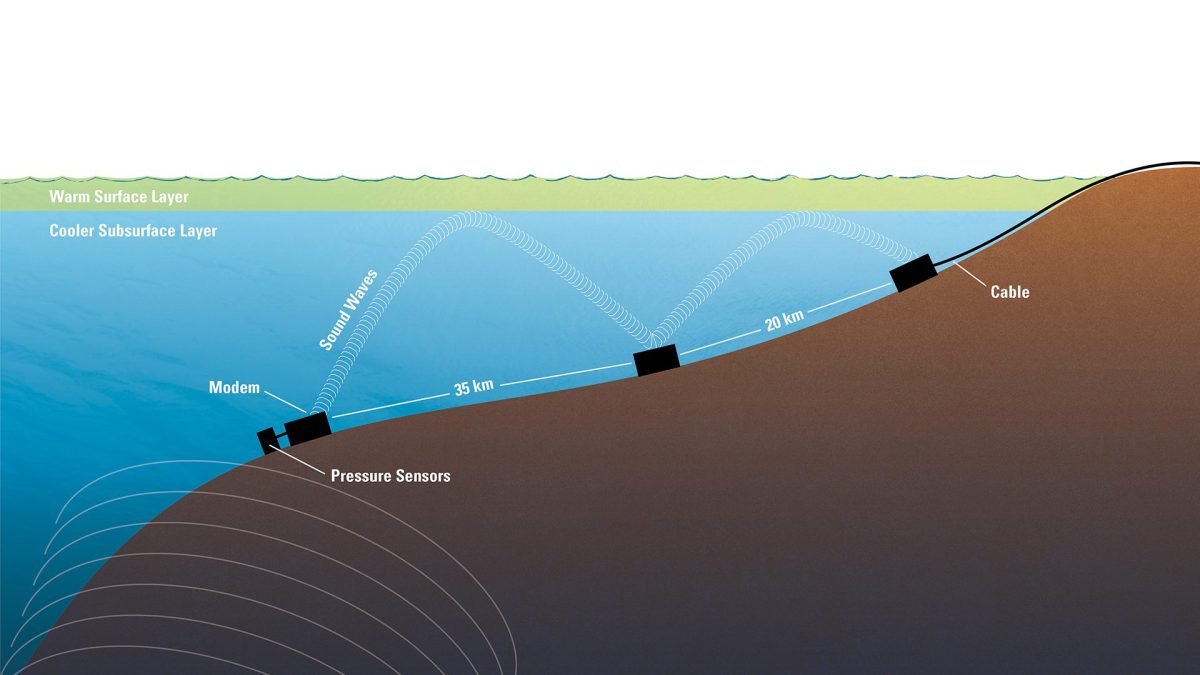

Warning systems include buoys and bottom pressure recorders to monitor real-time wave height, seismometers to detect earthquakes and other seismic activity, and satellites to relay data to tsunami centers, which evaluate conditions and issue warnings as needed. Each buoy is linked to a bottom pressure recorder; together they track the height of the water column, which allows researchers to observe the wave as it travels. Clusters of buoy-recorder systems have been deployed in strategic locations where tsunamis are more likely to occur. Buoys send data to satellites, allowing researchers to monitor conditions in near real-time.

Nations with coastlines likely to be affected by tsunamis have evacuation systems in place to alert people near the water to the threat posed by an incoming tsunami. Rapid communication between tsunami centers and people on the ground gives people the best possible opportunity to reach high ground before the first wave hits.

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Institution. Assessment of capacity building requirements for an effective and durable tsunami warning and mitigation system in the Indian Ocean; consolidated report for countries affected by the 26 December 2004 Tsunami. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnady256.pdf

Mori, N. et al. 2022. Giant tsunami monitoring, early warning and hazard assessment. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. doi: 10.1038/s43017-022-00327-3.

NOAA. The science behind tsunamis. https://www.noaa.gov/explainers/science-behind-tsunamis

NOAA. Tsunami Propagation. https://www.noaa.gov/jetstream/tsunamis/tsunami-propagation

NOAA. U.S. Tsunami Warning System. https://www.noaa.gov/explainers/us-tsunami-warning-system

NOAA National Data Buoy Center. Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis (DART) Description. https://www.ndbc.noaa.gov/dart/dart.shtml

NOAA Tsunami Program. https://www.tsunami.noaa.gov/

USGS. Indian Ocean Tsunami Remembered—Scientists reflect on the 2004 Indian Ocean that killed thousands. December 23, 2014. https://www.usgs.gov/news/featured-story/indian-ocean-tsunami-remembered-scientists-reflect-2004-indian-ocean-killed