Record-level heat is predicted for the months, and years, ahead. Why is this happening?

Ongoing climate change and a naturally-occurring El Niño event overlap to bring the heat

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

Unstoppable forest fires in Canada. Dangerous heat waves in the southern United States, Europe, and North Africa. Higher air and sea surface temperatures that melt glaciers, ice caps, and ice sheets. Summer is in full swing in the Northern Hemisphere, accompanied by discouraging, and often disastrous, news headlines are heralding the impacts of a warming world.

In the next five years, the World Meteorological Organization warns of a 66 percent chance, or roughly 2 out of 3 odds, that Earth’s global temperature exceeds the 2.7-degree Fahrenheit (1.5-degree Celsius) above preindustrial levels benchmark. They also project a 98 percent likelihood that at least one of the next five years will see Earth’s warmest on record, which date back to around 1850.

Why is the hot weather happening? And why now? The answer lies primarily in the overlap of ongoing climate change and a naturally-occurring El Niño weather event that results from interactions between the ocean surface and the atmosphere over the tropical Pacific.

“The most important thing to remember is that the projected record temperatures we’re heading towards are the result of the combination of El Niño and climate change,” said associate scientist Dr. Christopher Piecuch, who studies sea level change in the physical oceanography department at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. In other words, we don’t “feel” climate change primarily through the slow and steady rise in sea levels, or increase in global temperatures. But rather, he said, through extreme events.

This could occur when a stronger, longer-lasting tropical cyclone drives storm surge on a higher baseline sea level, inundating and flooding more of an area than a weaker, shorter-lived storm a century ago would have, Piecuch said. “Or when a punctuated climate ‘event,’ like a strong El Niño, rapidly raises temperatures and effects weather globally and regionally on top of the ever-warmer planet we live on,” he said.

Meteorological forecasts suggest that the naturally-occurring warming event El Niño, switching from its cooler counterpart La Niña and more neutral conditions, will return in 2023, increasing global temperatures the year after it develops. The hottest year in recorded history, in 2016, was driven by a major El Niño event.

During El Niño events, warmer waters in the tropical Pacific weaken trade winds and heat the atmosphere above, lifting global temperatures. The cooling influence of La Niña conditions over much of the past three years temporarily reined in the longer-term warming trend. The Climate Prediction Center at the National Weather Service predicts an 80 percent chance of a moderate El Niño developing in the coming months, with a 55 percent likelihood it will be “strong.” There’s also a 90 percent chance that it will remain into the Northern Hemisphere’s winter months.

The impact? El Niño, combined with human-induced climate shifts in temperatures, will “push global temperatures into uncharted territory,” said WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas in a press statement released after publication in May of their Annual to Decadal Climate Update.

For people, this creates a laundry list of concerns; among them, drought, fires, and disruptive changes to the natural world, from coral reef bleaching to shifting precipitation patterns. For the last three decades in the United States, extreme heat has been the greatest weather-related cause of death, with approximately 700 people dying annually, more than from hurricanes, tornadoes, flooding, or extreme cold, according to statistics from the NOAA National Weather Service.

Piecuch and other scientists point to rising trapped gases such as carbon dioxide but also methane and nitrous oxide in the atmosphere, frequently called greenhouse gases, produced primarily by burning fossil fuels like coal, natural gas, and oil for electricity, heat, and transportation as a cause for the rise in temperature.

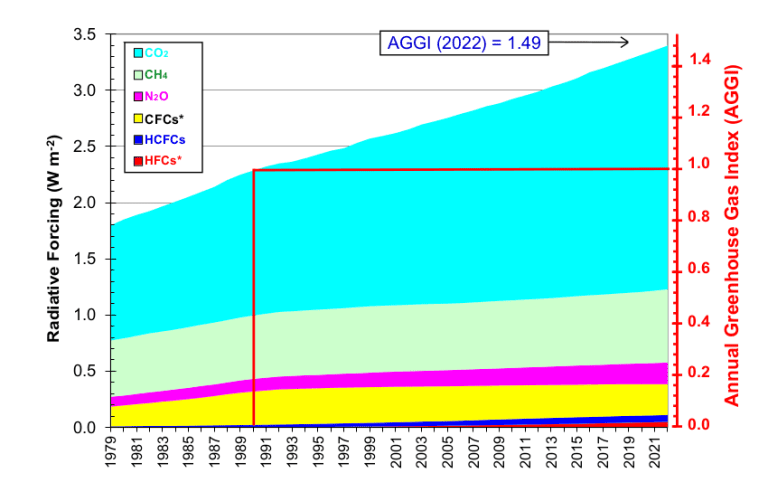

For example, during 2022, greenhouse gas pollution from human activity trapped 49 percent more heat in the atmosphere than those same gases did in 1990, according to NOAA’s Annual Greenhouse Gas Index, which tracks increases in the warming influence of heat-trapping gases generated by human activity. The warmth heats the ocean, causing expansion that takes up more space, pushing sea levels higher. Warmer waters also melt glaciers and ice sheets on the coasts, compounding the volume of water in the ocean and adding to the sea level height.

Off the East Coast of the United States a warming ocean has also impacted the continental shelf and slope, as well as marine organisms living there, said WHOI senior scientist and physical oceanographer Dr. Glen Gawarkiewicz. The Gulf of Maine and southern New England are among the most rapidly-warming regions in the world ocean, the combined result of the jet stream, fast-flowing air currents located in the upper levels of Earth’s atmosphere, and the naturally warmer, oceanic Gulf Stream current flowing into the North Atlantic. As the ocean heats further, it affects the seasonality and movement of fish and other marine life.

A less obvious influence is the heightened variability of the Gulf Stream, Gawarkiewicz said. In January 2013, he and colleagues first heard from the fishing industry about the increased frequency of Gulf Stream waters on the continental shelf. This led to a surge of research establishing that the Gulf Stream meanders more broadly. They found that large eddies, called Warm Core Rings, had significantly increased in number each year.

“The last two years have seen a significant increase in warming of the continental shelf,” he said. “That is something to watch closely, and hopefully we can get badly needed sub-surface observations to understand these rapidly changing conditions.”