5 essential ocean-climate technologies

In the race to find solutions to our climate crisis, these marine tools help us get the data to make informed decisions

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

It’s hard to overstate how profound the ocean’s role is when it comes to climate change. It has absorbed more than 90 percent of the heat caused by greenhouse gasses since the Industrial Revolution, and it stores nearly one-third of the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions we produce, staving off 4-6°C (7.2-10.8°F) of planetary warming. But as much as it benefits our climate, the ocean also suffers from its effects—problems like biodiversity loss, heatwaves, and ocean acidification. With this in mind, innovative technologies are needed to monitor changes in the ocean over time and help develop ocean-based solutions for our climate challenges.

From the poles to the ocean twilight zone, here are some of the most important tools WHOI scientists use to monitor the ocean’s role in, and response to, climate change.

Argo floats

An Argo float is deployed off the side of a research vessel. (Photo courtesy of the Argo Program, UC San Diego)

These free-drifting instruments measure a variety of parameters in the ocean that help researchers understand the ocean’s response to climate change. This includes regional and global changes in ocean temperature and heat content, salinity and freshwater content, the height of the sea surface in relation to total sea level, and large-scale ocean circulation patterns. Typically deployed from ships, Argo floats autonomously travel from the ocean’s surface to a depth of 2,000 meters (over 6500 feet) and back up again, getting a more complete profile of the upper and middle layers of the ocean. Click here to see where Argo floats are currently measuring the ocean.

Ice-tethered profilers

WHOI researchers Kris Newhall (left) and Rick Krishfield (right) and Brian McKenzie set up an Ice-Tethered Profiler to monitor Arctic conditions. (Inset) The plug-like top of an ITP sits atop an ice floe in the Beaufort Sea. (Photos by Gary Morgan and John Kemp, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

These large, bright-yellow surface buoys sit atop ice floes like construction barrels on a snow-covered highway, tracking ocean parameters around the clock. Hanging from each buoy is a weighted cable that dangles through an 11-inch-diameter hole in the ice and into the ocean. A motorized sensor package travels continuously up and down the tether through various layers of the ocean in yoyo-like fashion, taking continuous measurements of temperature, salinity, and other seawater properties along the way. Data from these profilers, combined with ship-based observations, give scientists the ability to quantify changes over the past several decades and have helped reveal the unexpected scale and speed of ocean warming.

Chanos II

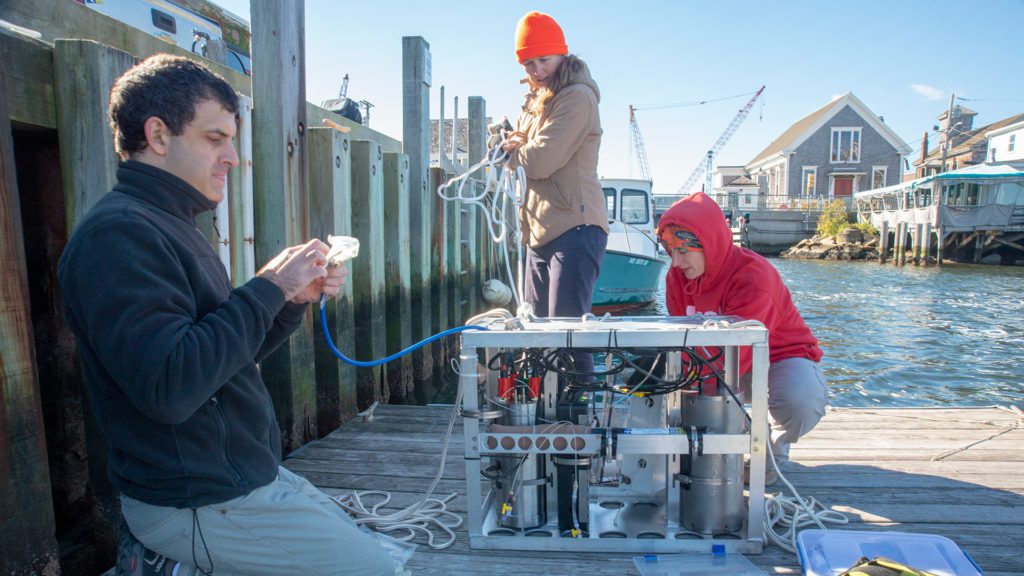

Former WHOI postdoctoral investigator Eyal Wurgaft, WHOI Research Assistant III Kate Morkeski and former MIT-WHOI Joint Program student Mallory Ringham prepare CHANOS II for tests. (Photo by Jayne Doucette, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Chanos—which is short for The CHannelized Optical System— is an optical sensor that can make rapid measurements of the ocean's carbon chemistry, including Dissolved Inorganic Carbon (DIC) and pH. It can be deployed autonomously from docks, buoys, and mobile platforms like remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), reducing the costs associated with sending scientists out to sea to gather seawater samples. With it, scientists can make valuable observations of how the ocean's chemistry may be changing in response to climate change. For example, it can help determine the extent to which seawater is becoming more acidic as it absorbs increasing amounts of CO2 from the atmosphere.

The Polar Sentinel

It looks like a cruise missile with wings, and has bells and whistles that would excite any oceanographer attempting long-range under ice surveys. The Polar Sentinel is an AUV-glider hybrid that can travel thousands of miles below the surface of the Arctic Ocean to measure ice thickness, all with the power draw of a cell phone. Inside the vehicle’s nose is a sonar system that provides an X-ray-like profile of the ice as it cruises several meters below the frozen surface. A high-efficiency thruster in the rear of the vehicle keeps the glider going across huge swaths of the ocean, and ensures that it stays ahead of the fast-moving ice pack. What’s more, a Doppler sonar module provides navigational guidance based on the terrain of the seafloor.

Deep-See

Deep-See is a towable sensor platform that helps scientists estimate and identify the creatures of the ocean’s twilight zone (OTZ), many of which help move CO2 from the surface to deeper waters. At the front of its Formula-1-sized frame are stereo cameras and two different kinds of sonar technologies that can scan and map the volume of life in the OTZ before it migrates to and from the surface waters. Research vessels can tow Deep-See, while it glides at depths of up to 1,000 meters (3,000 feet). Underwater, samplers at its midsection can capture genetic information for species identification, while other sensors take chemical measurements of the water’s pH, salinity, and more. An electro-optical cable sends all this information in real-time to scientists in the ship’s wet lab—data that can inform policy makers and stakeholders about how to manage this ecosystem sustainably.