WHOI builds bridges with Arctic Indigenous communities

NSF program fosters collaboration between indigenous communities and traditional scientists

By Elise Hugus | February 10, 2021

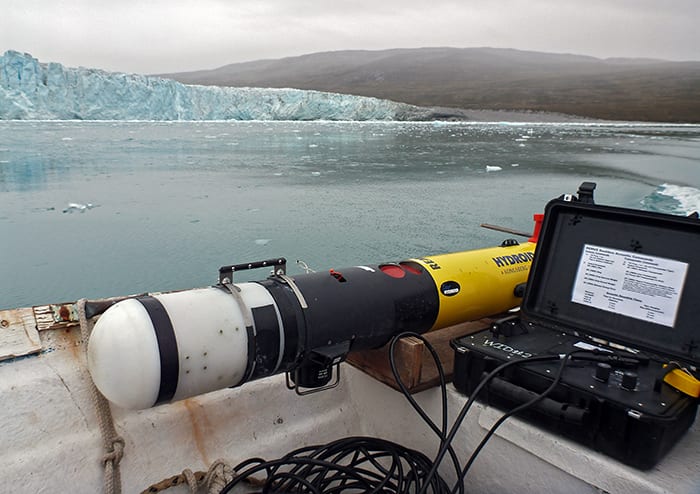

It was a calm, frigid day in Utqiagvik, Alaska (formerly Barrow), in the winter of 2010. WHOI researchers Amy Kukulya and Al Plueddemann had just finished setting up a field site on a stretch of pack ice in the Chukchi Sea. They were looking forward to the next day, when they would begin testing a new autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), a cold temperature-adapted REMUS lovingly dubbed “The Icebot.”

Later that day, their colleagues at the Barrow Arctic Science Consortium (BASC) started to get worried. They burst into the warehouse where Kukulya and Plueddemann were prepping equipment, grabbed a snowmobile, and said, “We’re going back out on the ice.” Bewildered, the researchers awaited their return.

“Within the hour after leaving the site, something about the wind and current changed directions, enough for only a local native to know there was something about to happen. They had a sixth sense,” Kukulya recalls.

As radar imagery would later show, an ice floe had broken up offshore and traveled rapidly landward. The impact at the test site was so great that ice chunks piled up five meters high. When the BASC personnel returned with pieces of tent and the gantry, Kukulya remembers feeling humbled by their innate understanding of the dynamic Arctic environment.

Since that experience with the Icebot, Kukulya has returned to the Arctic several times. This summer, she plans to test out her latest project—a long range autonomous underwater vehicle (LRAUV) capable of tracking oil under sea ice— and connect with Iñupiat communities that could use this technology as first responders in the event of an oil spill. She’s working with native Alaskan community groups to develop other applications, such as monitoring for marine mammals or developing better navigation and weather prediction tools.

“We don’t want to invade the community with a robot on our backs. We want to show them what’s possible and ask them what they need,” says Kukulya.

In recognition of the value of local insight in the changing polar region, the National Science Foundation created a program called Navigating the New Arctic (NNA)—one of the agency’s ten Big Ideas. Now in its third year, the program has funded a variety of environmental and social science projects aimed at the “co-production” of indigenous knowledge and Western science.

“In order to tackle really challenging problems throughout the world, we need to recognize the complex interdependencies between the natural, social and built environment,” says NNA program director Irina Dolinskaya. “We need the perspectives of people who have been living in the Arctic for hundreds of years, not only as users, but also as knowledge producers, identifying research questions and methodologies from the beginning.”

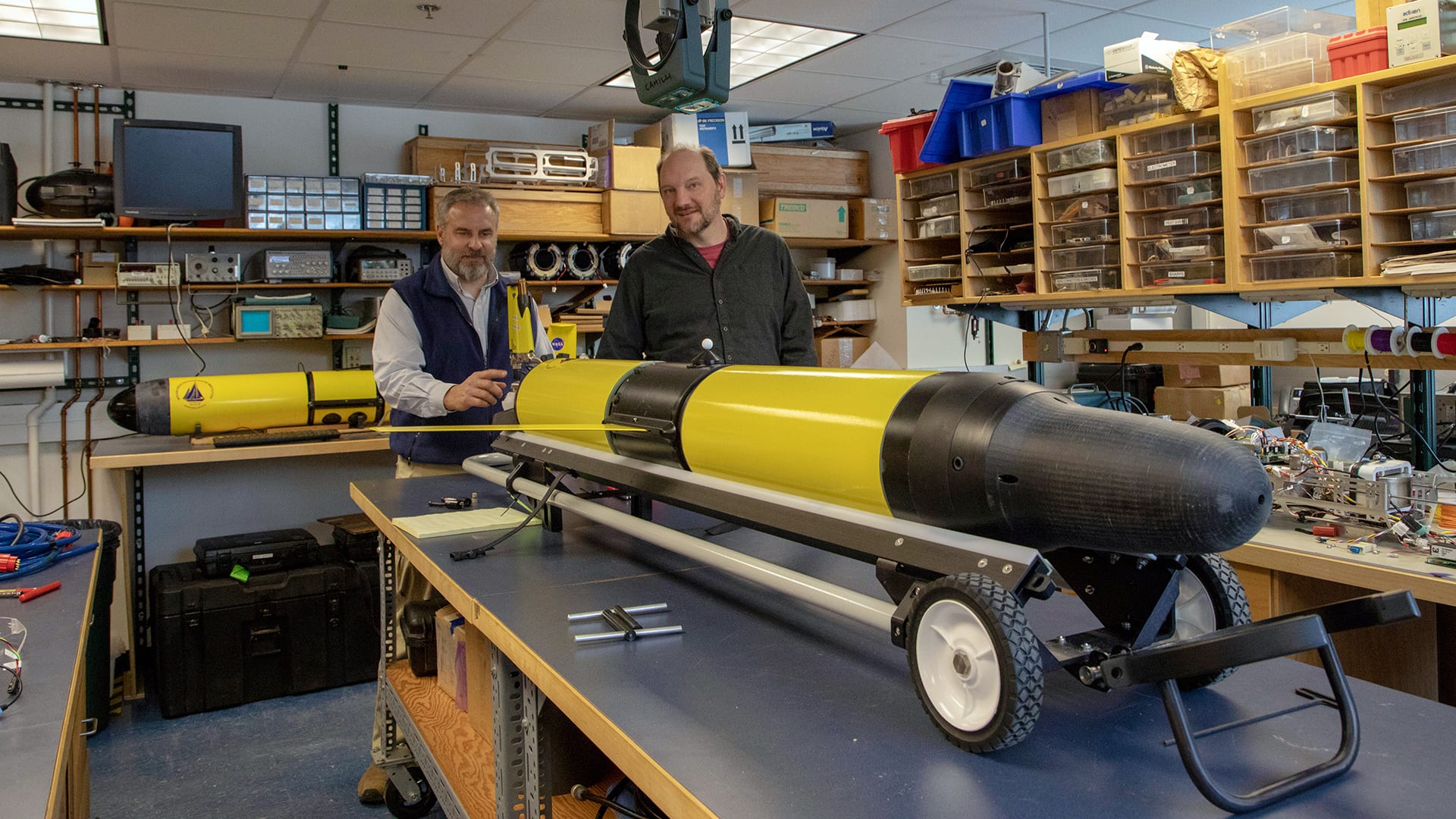

In the first year of the NNA program, WHOI engineers Ted Maksym and Rich Camilli received funding to develop an AUV-glider hybrid called the Polar Sentinel that can measure ice thickness— as well as salinity and temperature changes— from under the ice. This capability is crucial for establishing a baseline that Arctic communities can use to interpret changes, for example, to ocean currents or ice melt patterns.

“This is a very unique, state-of-the-art technology that will hopefully help build other projects,” Dolinskaya says. “The most immediate need is to better understand the ice itself, but with other sensors we can also potentially track marine life, which is absolutely critical to the livelihood of coastal communities. That’s how they survive.”

Pending Covid-19 travel restrictions and other logistical challenges, Camilli’s team plans to survey a 900-kilometer area along the edge of the Arctic ice cap. After initial testing, they plan to make the technology available to native communities and researchers already working in the region.

“We’d love to be able to hand off these capabilities so researchers from elsewhere won’t be needed to operate this vehicle,” Camilli says. “There’s so much local knowledge already there. If they see something changing, they can just send the vehicle out. It helps on so many levels to improve observational data from citizen scientists.”