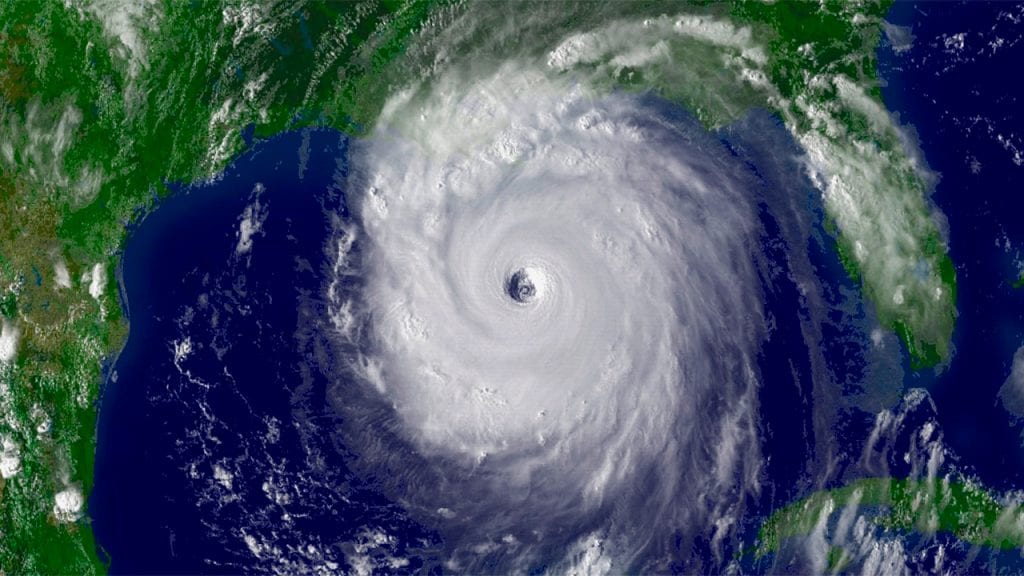

(Photo courtesy NOAA)

What are hurricanes?

In the tropics, sunlight heats the ocean’s surface, causing water to evaporate into the atmosphere. The rising air mass creates a low-pressure zone that draws in air from surrounding areas, and strong, steady winds rush in to fill the space left behind. When atmospheric conditions are right, these winds can develop into a tropical disturbance. Earth’s rotation deflects the winds, causing them to spin around the low-pressure center, creating an “eye” at the center of the storm. During summer months, when sea surface temperatures reach at least 26° Celsius (about 80° Fahrenheit), high levels of evaporation can cause the disturbance to strengthen into a hurricane.

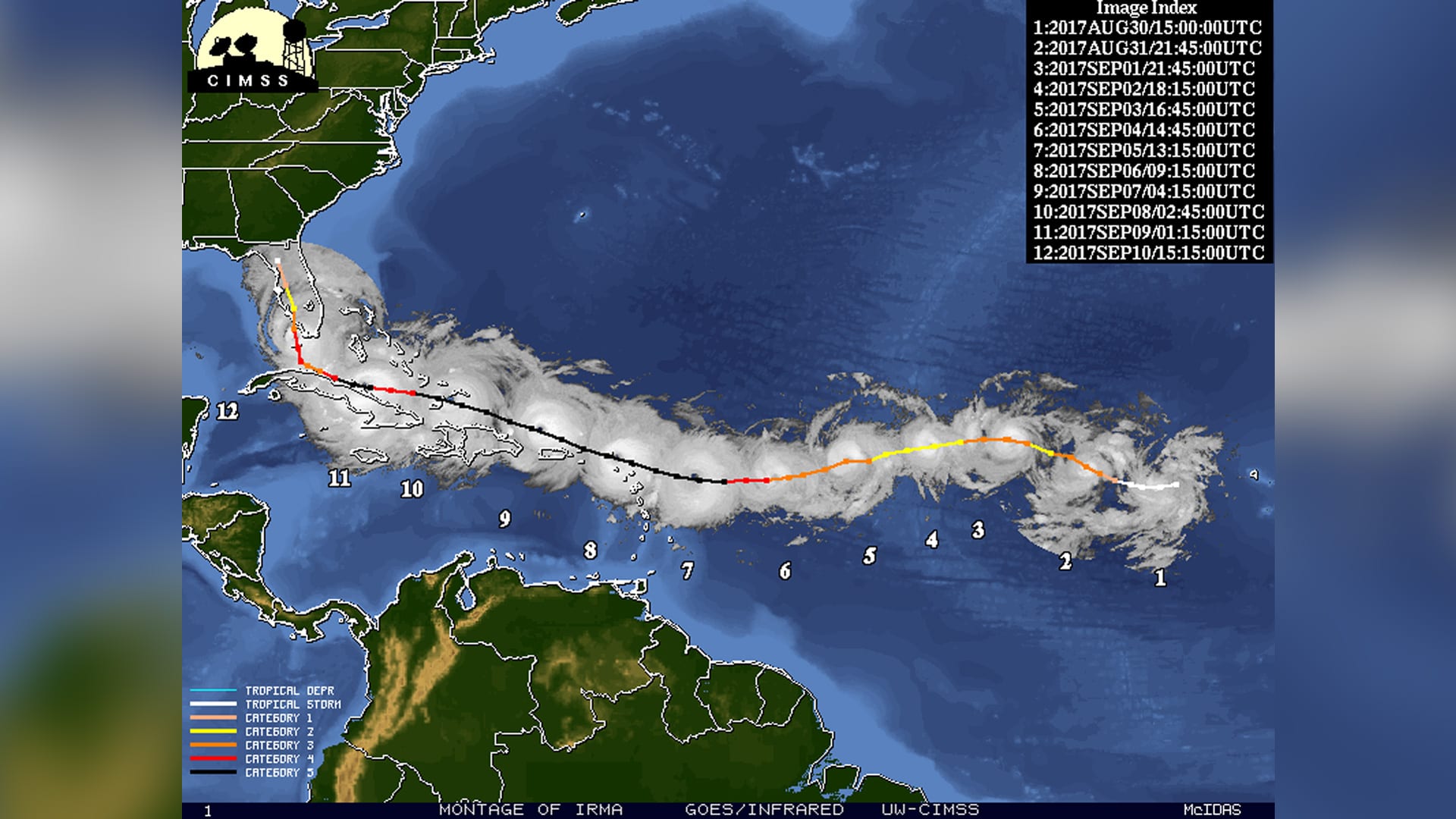

We use the strength of those winds to categorize tropical disturbances. When they are first developing, and winds remain below 39 miles per hour, we call it a tropical depression. As it gains strength and wind speeds increase, it becomes a tropical storm. Once winds exceed 74 miles per hour, we call it a hurricane. Hurricanes are categorized by sustained wind speed, ranging from a dangerous category 1 (speeds of 74 to 95 miles per hour) to a catastrophic category 5 (speeds exceeding 157 miles per hour).

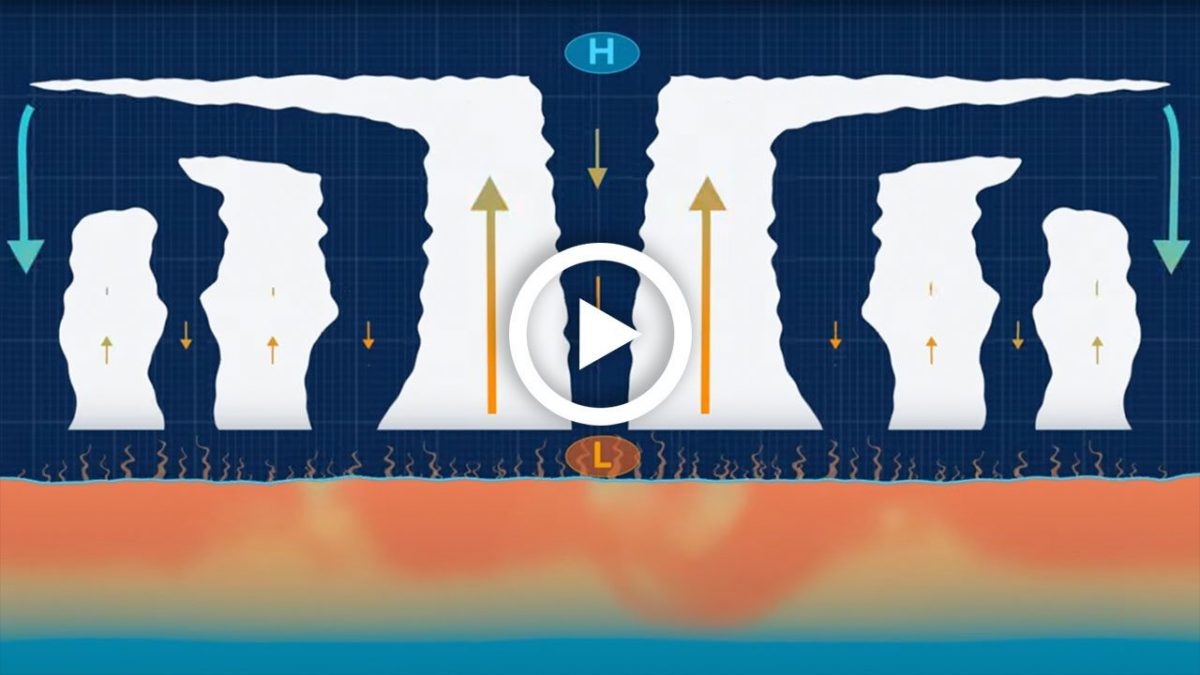

Most Atlantic hurricanes begin to form over Africa, where hot, dry desert air meets cool, wet air. In the seam between these high- and low-pressure air systems, a powerful westward stream known as the African Easterly Jet forms. Atmospheric disturbances that break off from the swerving jet can trigger hurricanes. (Illustration by Natalie Renier, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Why are hurricanes important?

Spanning hundreds of miles, hurricanes are the biggest storms on the planet. They bring strong winds, heavy rain, and large storm surges to coastal areas when they make landfall, damaging property, downing trees and power lines, and endangering human lives. The economic costs of hurricanes are extensive, ranging in the billions of dollars each year for the United States alone. Since 2018, the U.S. has seen an average of 18 weather and climate-related events each year that caused more than a billion dollars in damage.

The National Hurricane Center tracks developing tropical storms and issues warnings to minimize risk to people in the storms’ paths. Their models provide good forecasts of the track a storm might take, so people can evacuate if needed. However, the need to evacuate is also tied to a storm’s intensity—how strong the winds blow. In recent years, a number of hurricanes have rapidly intensified into catastrophic storms shortly before making landfall, increasing the need to evacuate but giving people little time to do so.

What are ocean scientists doing to better predict hurricanes?

Although models do well predicting the track a hurricane will take, they often struggle to predict intensity, making it difficult for officials to determine the most effective evacuation orders. Difficulty in predicting intensity lies in a lack of data about ocean temperatures.

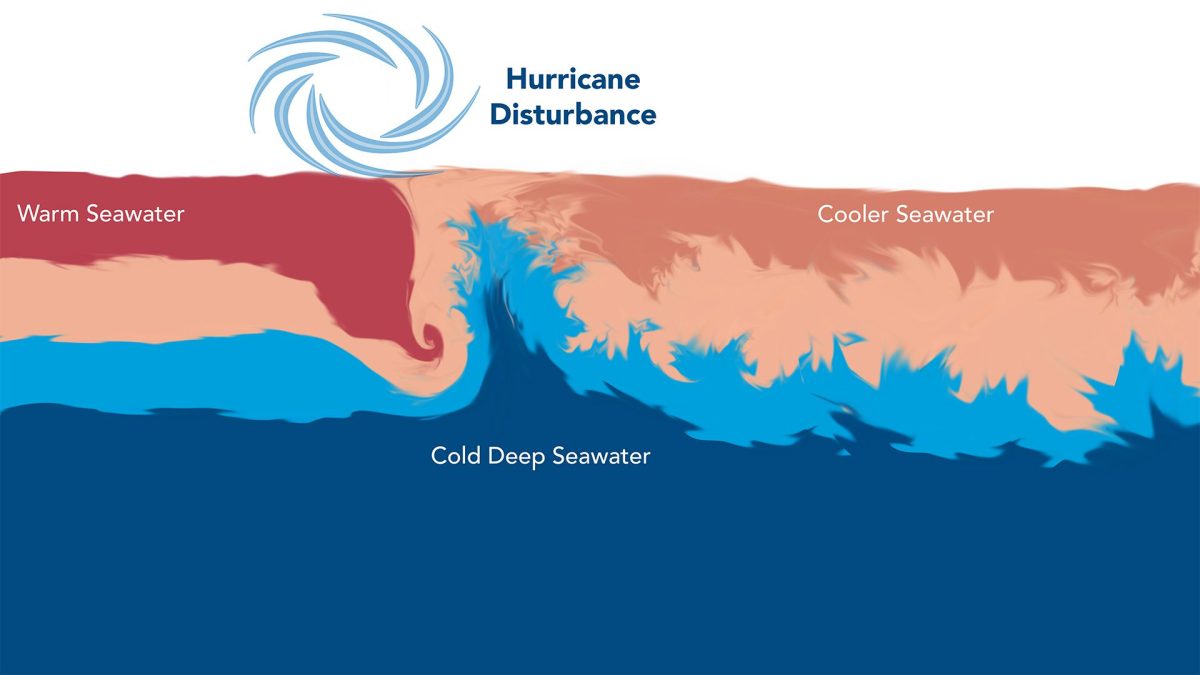

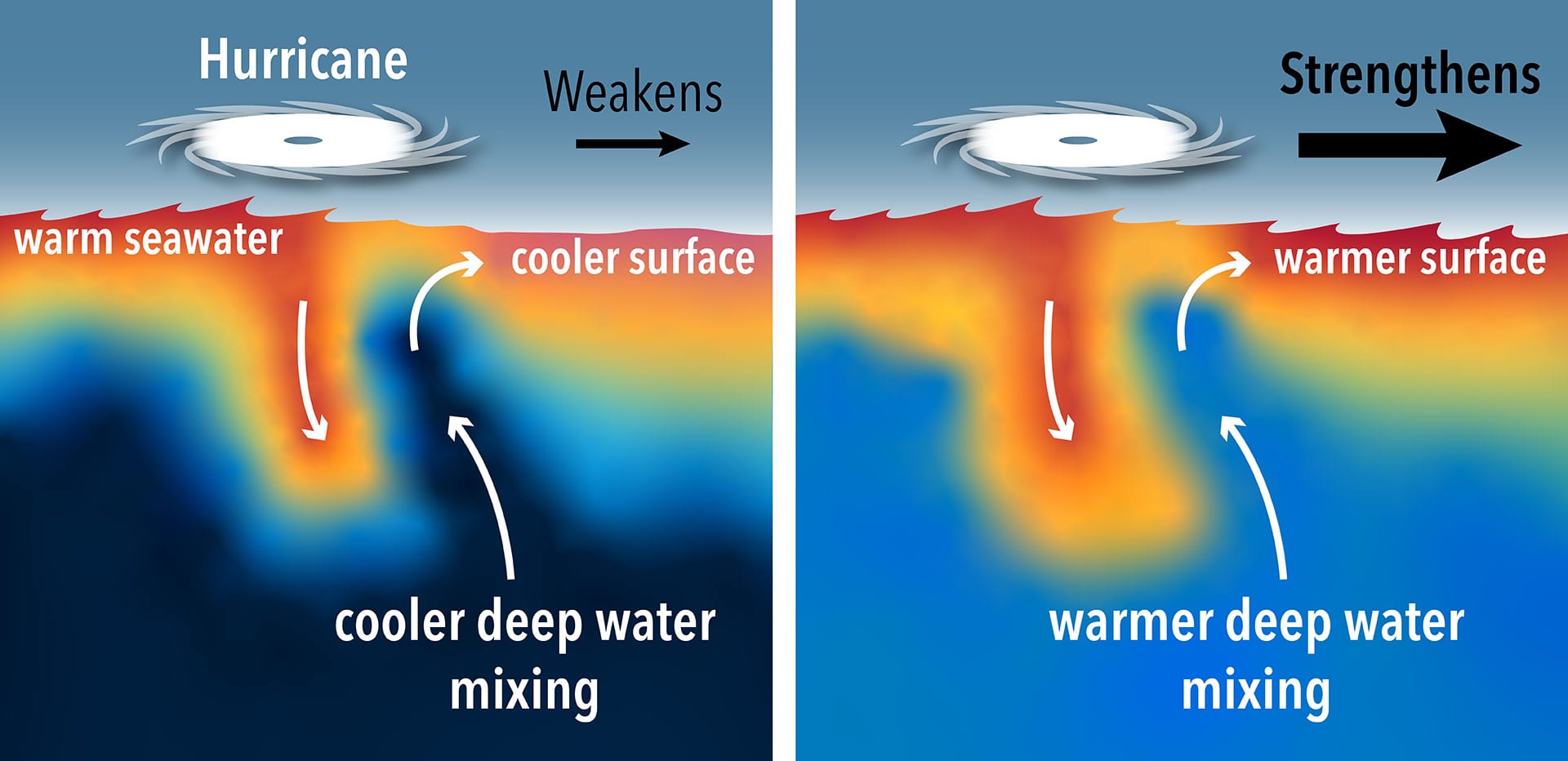

Hurricanes draw their energy from warm sea surface waters. As lower strata of the ocean warm up along with the rest of the planet, deeper waters once cool enough to weaken hurricanes at the surface, are now becoming warm enough to strengthen them. (Illustration by Natalie Renier, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Heat in the upper layers of the ocean power these massive storms. Although satellites can detect sea surface temperature, those measurements don’t penetrate more than a few inches. The key to a hurricane’s strength lies deeper. As its winds churn the waters below, deeper, cooler waters upwell and mix with warmer surface waters. If this happens, the cooler water robs the storm of strength. But when the warm surface layer lies atop a deeper layer of warm water, this churning instead fuels the storm. When those waters are warm enough, they lead to rapid intensification.

Can scientists measure the depth of warm water?

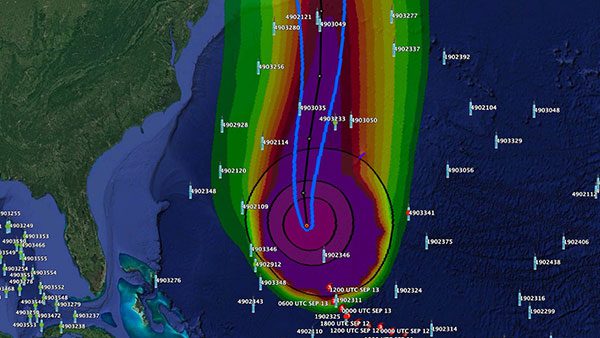

To improve this aspect of hurricane forecasting, researchers have begun to gather data on the state of the ocean before, during, and after a tropical storm passes through. These data can only be gathered from the water column, and researchers use a variety of instruments to measure temperature, pressure, and salinity (salt levels). Autonomous robots, such as Spray gliders and Argo floats, remain in the ocean for months at a time gathering data. Other instruments, such as the Ocean Observatories Initiative Pioneer Array, are moored in place. When tropical storms cross paths with these instruments, they can provide vital, near-real-time data to help better predict storm intensity.

ARGO floats in and near Hurricane Lee, September 2023.

Can scientists measure hurricanes that aren’t near existing sensors?

Not all storms pass near previously installed instruments, so WHOI researchers have developed ALAMO floats specifically designed to collect essential ocean data before, during, and after a storm. Launched from Hurricane Hunter airplanes, these instruments parachute into the water in the path of an oncoming storm. They begin to function once they reach depth, cycle through a quick diagnostic, and then begin rising and falling through the water column, taking the water’s temperature and sending it to scientists via satellite. These data are then fed into models, so they can more accurately predict changes in the storm’s intensity as it approaches land. The hope is to improve evacuation recommendations and reduce loss of life as a warming world brings more frequent, high-intensity storms.

This montage of satellite images shows Hurricane Irma and its shifting intensities as it tracked across the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea in August 2017. (Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies Space Science and Engineering Center/University of Wisconsin-Madison)

What can we learn from past hurricanes?

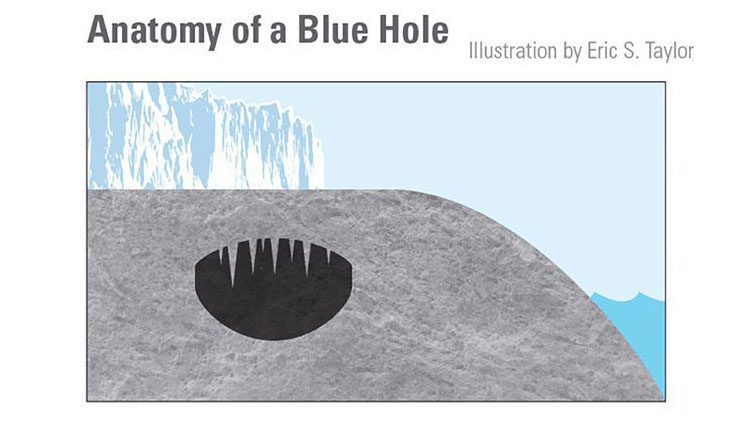

Scientists study evidence left by hurricanes from several hundred years ago to improve our understanding of future hurricanes. How does a scientist study a hurricane that hit in the 1400s? When a hurricane approaches a coastline, it tends to whip up sandy seafloor sediments and organic debris and fling them into nearby coastal areas where they get buried over time. Scientists can unearth this ancient submerged evidence with long, metal, straw-like tubes that extract cores from the bottom of coastal ponds or lagoons, salt marshes, or blue holes in the open ocean. They analyze the cores to help determine the frequency and severity of long-ago storms, understand the factors that generated past hurricanes, and help predict future hurricane patterns.

Jayne, S.R. et al. The Air-Launched Autonomous Micro Observer. American Meterological Society. April 2022. doi: 10.1175/JTECH-D-21-0046.1.

Kostel, K. New air-launched devices help study hurricanes. Oceanus. October 19, 2017. https://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/feature/oceanography-takes-flight/

Lubofsky, E. As Hurricane Laura raged, silent sentinels kept watch from below. WHOI. August 28, 2020. https://www.whoi.edu/news-insights/content/as-hurricane-laura-raged-silent-sentinels-kept-watch-from-below/

Lubofsky. E. WHOI prepared for 2019 Atlantic Hurricane Season. July 18, 2019. https://www.whoi.edu/news-insights/content/whoi-prepares-for-2019-atlantic-hurricane-season/

National Hurricane Center. https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/

NOAA. Hurricane Costs. https://coast.noaa.gov/states/fast-facts/hurricane-costs.html

NOAA. Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/aboutsshws.php

Showstack, R. WHOI scientists monitor the ocean with innovative tools and techniques to improve hurricane forecasting. WHOI. October 4, 2021. https://www.whoi.edu/tools-and-techniques-to-improve-hurricane-forecasting/