How WHOI’s young pioneers once tried to look for the lost city of Atlantis

By Brett Freiburger | February 3, 2021

More than 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Plato told the story of a wealthy civilization that sank into the sea after a barrage of fire and earthquakes. That city, known today as the fabled lost continent of Atlantis, has gripped the human imagination ever since. It would only be fitting that when a new oceanographic institution began 90 years ago in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, it would have the drive and research capacity to investigate whether this city actually existed.

It was 1931, soon after the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s inception, when the field of ocean science was still relatively new. WHOI oceanographer and founding director, Henry Bryant Bigelow, and fellow ocean pioneer and first mate Columbus Iselin set off on a 42 day research cruise around the Azores, hoping to investigate how large currents like the Gulf Stream powered aspects of North America’s climate. The two scientists, both Harvard scholars well-versed in the humanities, would not be able to resist an opportunity to comb the seafloor for signs of the ancient metropolis.

WHOI oceanographer and founding director Henry Bryant Bigelow thought everyone in the lab, including himself, should go to sea at least once each summer. Here he is at work aboard Atlantis in 1932, a year after his attempt at looking for the lost city. (WHOI Archives, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Until their expedition, only a morsel of anthropological evidence could serve as a clue: the city was said to exist on an island Plato once described as “situated in front of the straits which are by you called the Pillars of Heracles.”

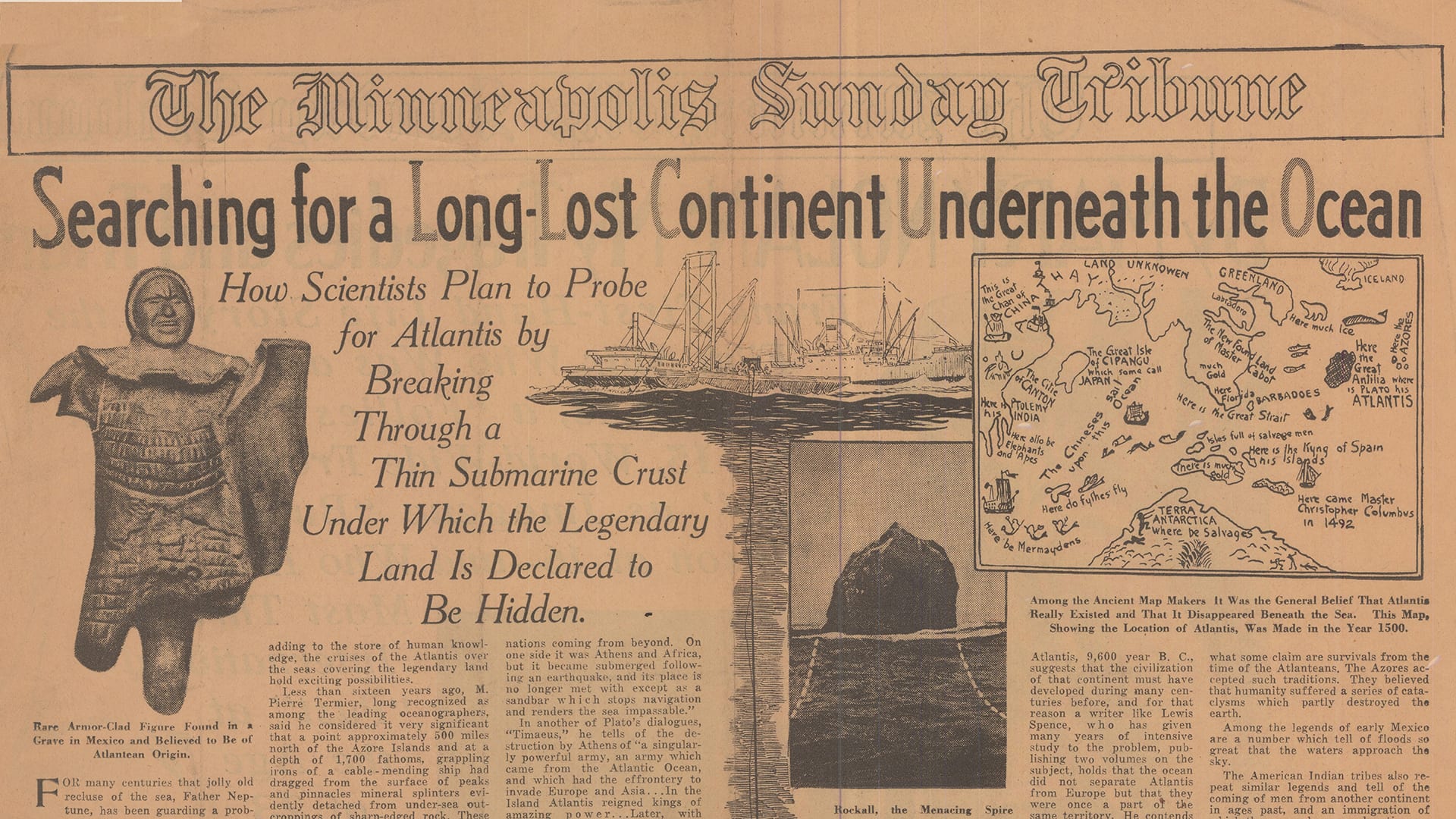

The Minneapolis Sunday Tribune covered the story in October of that year, informing readers that, “scientists plan to probe for Atlantis by breaking through a thin submarine crust under which the legendary land is declared to be hidden.” With Iselin as the crew’s chief scientist and several “well-equipped laboratories between decks,” it was hoped that the team of scientists studying the so-called Atlantean Plateau would confirm once and for all the question of Atlantis’ existence.

At the time, Bigelow’s team planned to scrape off and collect the “top dressing” of seafloor, and then, using deep sea acoustic soundings, look deeper for ancient artifacts or structures embedded there. The nature of the soil they discovered would, the researchers hoped, also tell them whether or not the continental plateau that Atlantis sat on was once high and dry as Plato noted in works “Timaeus” and “Critias.” Perhaps it would reflect the soil of Africa, South America, or New York, they thought; or maybe there’d be granite, evidence of volcanic eruptions, or even remnant coral structure. All of this would help to determine if the surveyed areas were once high enough above sea level to sustain human civilization, and whether Plato’s accounts of catastrophe were indeed true.

For the institution’s first research vessel, a 140-foot ketch aptly named Atlantis, this would be among the first voyages across the Atlantic over the summer of 1931. On the voyage to Woods Hole from a shipyard in Europe, the crew had conducted preliminary soundings and, the Minneapolis Tribune article read, made “deep sea tests,” of the “grapplers, hooks, and borers to be used in probing for the lost continent.” Earlier searches by other oceanographers indicated that WHOI scientists might only need to break through 10 inches of sediment to discover evidence of Atlantis. But after more than a month at sea and their other research projects were completed, the crew returned home empty-handed. No mention of any new findings regarding Atlantis can be found in their logbooks.

WHOI ocean engineer Jim Mavor, along with colleagues Edward Zarudski, Dr. Hatzikakides, departs on a research boat in Thera, Greece to look for remnants of Atlantis, c. 1966. (Courtesy of WHOI Archives, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Yet the story of Atlantis was to surface again at the Institution. In 1966, more than 30 years after Bigelow and Iselin’s expedition, oceanographic engineer James Mavor worked with scholars in Greece to locate a lost city on the bottom of the Mediterranean.

Off the coast of the island Thera in the Aegean Sea, Mavor and fellow researchers found evidence of a Minoan city dating to 1,400 B.C.E.

The city appeared to have been destroyed by a powerful earthquake and volcanic eruption, mirroring Plato’s description of the fall of Atlantis. But years of disputing over who deserved credit for the discovery left Mavor’s findings mired in doubt and skepticism among the public. Seemingly dejected after years of work, he went on to write a book about his search for Atlantis and how his findings squared with the writings of Plato.

Reports of the discovery of the ruins of Atlantis have surfaced countless times since Mavor’s attempt, but no conclusive evidence of its existence has ever emerged. Today, few scientists would now stake their careers on a search for Atlantis, yet more than 75 new books have been published about it in the last two years. For now, the lost city lives on, if only in the popular imagination.