Forged in fire: WHOI recalls the Deepwater Horizon crisis

By Daniel Hentz | April 20, 2020

A tower of smoke forms as oil and gas burn off the surface near the crippled Deepwater Horizon oil rig. (Photo by Cabell Davis, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Frontline WHOI scientists face unprecedented challenges when called to respond to the largest accidental oil spill in history.

Twenty miles from the wreckage of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, the research vessel Endeavor approached the site with a suite of oceanographic instruments, an intrepid autonomous vehicle, and a cadre of WHOI scientists. Facing the glow of a red sky lit by the flames of burning aerosols miles away, the WHOI crew steadied themselves for the daunting work that lay ahead.

It’s been a decade since the explosion of the BP oil rig that left 11 dead and unprecedented environmental damage, including the 57,000 miles covered by the oil slick, and the more than 100,000 wildlife trapped or killed by it. In need of answers at the onset, members of a U.S. task force—including the U.S. Secretary of Energy, Department of Interior, U.S. Coast Guard, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)—reached out to scientists at WHOI to see if they could find the cause of the broken wellhead and track the billowing oil plume. In response, a team of WHOI deep-sea and chemistry experts was dispatched to the scene. There, the hazardous conditions and crushing deadlines under which they worked became some of the most indelible memories they carry with them today.

“It was like being in a war zone,” says WHOI senior scientist Dana Yoerger, who was there to operate WHOI's autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry.

In the 20-mile radius exclusion zone surrounding the gushing wellhead, hundreds of ships converged; many were BP’s intervention vessels, contracted to siphon and burn off dangerous gases, and spray over 700,000 gallons of soapy dispersants into the air and water to quell the fumes.

Underwater, acoustic crosstalk from other submersibles made operating Sentry—brought to map the spill—that much more daunting.

Feeling the heat

While Sentry operated below, responders ran giant industrial skimmers to collect oil along the water’s surface and burn it. WHOI’s crew worried the vehicle would be accidentally snatched on ascent and incinerated in the mix.

On the surface, chief scientist and engineer Rich Camilli and his team were tasked with affixing WHOI’s arsenal of sonic equipment onto minivan-sized remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) to investigate the volume of oil leaking nearly a mile (1,500 meters) below. To do so meant spending time aboard the colossal response vessel, Ocean Intervention III, which sat directly above the blowout amid flames and nauseating chemical fumes.

Camilli says being dressed head-to-toe in protective equipment in this environment was like wearing a snowsuit in 110°F heat. “It felt like standing too close to a bonfire,” says Camilli. “The fumes were so powerful we had to wear respirators even when we slept below deck.”

Working in these harsh conditions made otherwise routine tasks require a whole new level of focus. In a deep sweat, Camilli and marine geochemist Chris Reddy launched devices, like the Seewald Sampler, which took two crucial pressurized samples directly from the wellhead for analysis back at WHOI. Knowing exactly which compounds were escaping Deepwater's holds would give marine chemists a chance to predict its effects on the natural world.

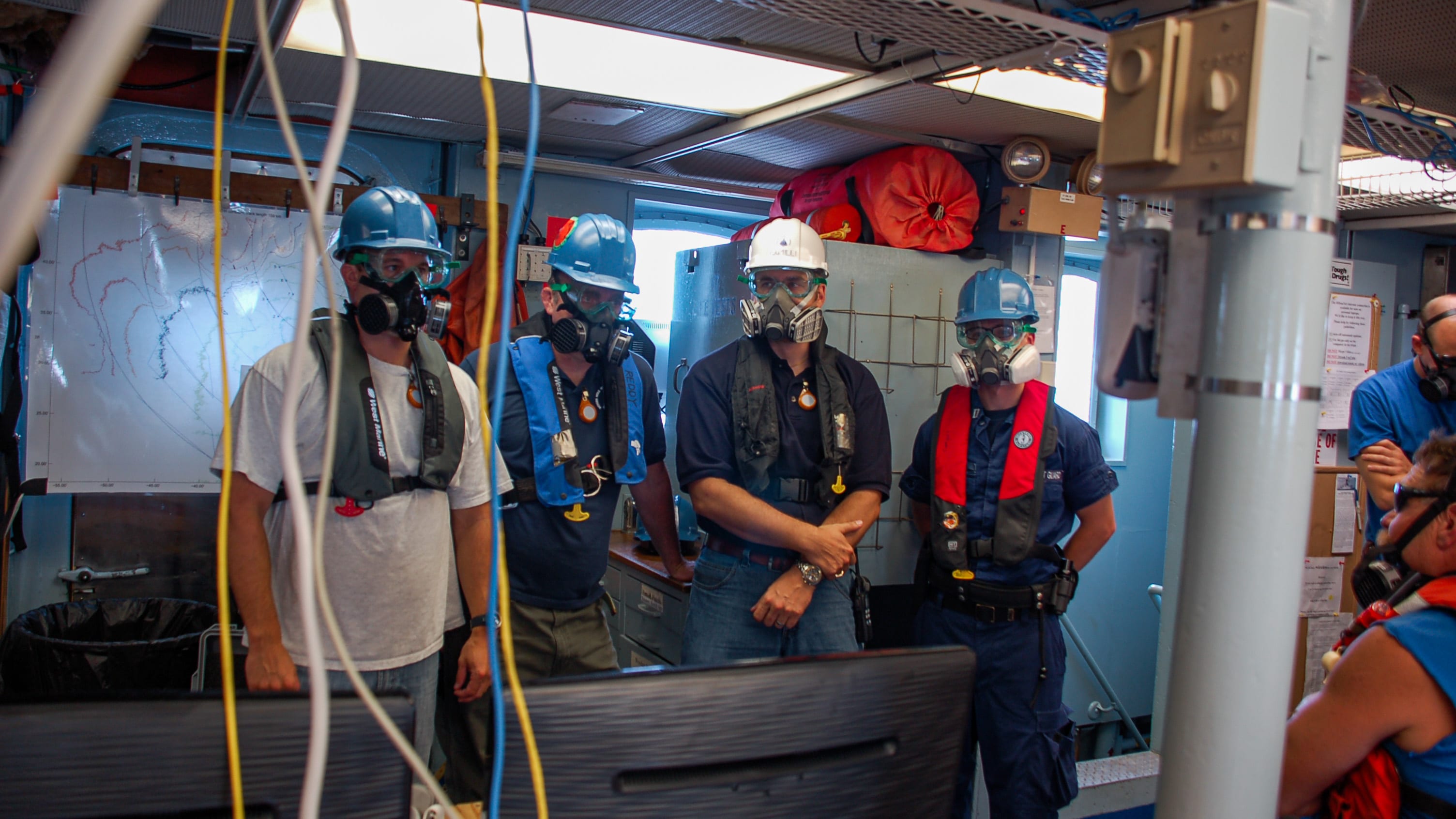

Members of the WHOI team (left to right) Sean Silva, Chris Reddy, and Rich Camilli don VOC respirators during their final briefing before being transferred from the R/V Endeavor to the Ocean Intervention III during the Deepwater Horizon response. (© Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

A race against time

When Camilli and National Deep Submergence Facility Director Andy Bowen first arrived to analyze the broken wellhead, they knew access would be tight.

In the 96 hours of bottom time allotted to operate their ROV, most of it was spent waiting for short windows of opportunity in between ongoing response operations to measure the oil’s flowrate; only a cumulative 15 minutes were available for them to get close enough to make observations. The two had never worked with so many industrial submersibles around them before. Some vehicles attempted to halt the flow, some sawed off well components to clear the way for closer inspection, while others hauled huge pieces of the riser to the surface.

Twenty miles from the leak, Reddy and colleague Ben Van Mooy worked round-the-clock on the Endeavor to take water samples near the sprawling plume. Reddy was constantly on call, barely able to sleep due to frequent requests for Coast Guard-ordered reports and updates.

“When I was sleeping, I never went to my bunk,” recalls Reddy. “I was lying down in the main lab with my phone on my chest waking up from alarms every half hour to check on [measurement readings].”

These samples were crucial: they would eventually identify the evolution of the plume, its direction, and changing chemical composition—details that would inform efforts to deal with the aftermath once the fires had subsided. Many samples were immediately analyzed on board the Endeavor.

Others, like the two pressurized samples taken by the Seewald Sampler from the wellhead, were highly guarded: locked in a pelican case handcuffed to Coast Guard officers, transported to Massachusetts, and hand-delivered to Reddy’s lab, where research specialist Bob Nelson worked to identify their composition.

The routine became one of the greatest relay races Reddy and his colleagues had ever run: launching Sentry to locate oil, waiting for its encoded messages to come back, and moving the boat accordingly to take water samples and measure oxygen. The non-stop exercise ran for weeks, with seemingly no end in sight.

AUV Sentry awaits its next mission to locate oil escaping Deepwater Horizon. (Photo by Chris Reddy, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

A model for future emergency response at sea

WHOI had never conducted fieldwork in such a high-risk environment. But that risk provided needed perspective for many. Particularly for Camilli, who sees the disaster as a clarion call to reevaluate how we manage our oceans going forward.

“We still treat the ocean like hunter-gatherers...but there clearly needs to be an active management component to the ocean,” says Camilli. “If anything, [the Deepwater Horizon experience] warrants more oceanography.”

That WHOI could adapt numerous methods used for scientific studies—hydrothermal vent exploration, natural oil seep measurements, and forensic marine chemistry—at a moment’s notice to provide assistance in a national emergency, was—and still is—a success. For Bowen, all that pressure and oversight simply underscored the immediacy and importance of the work being done at WHOI.

“You have a more refined sense of risk after something like this,” says Bowen. “At one point, you’re immobilized by a personal and environmental concern, but you keep going because there was a job to do.”

For more on Deepwater Horizon: