Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

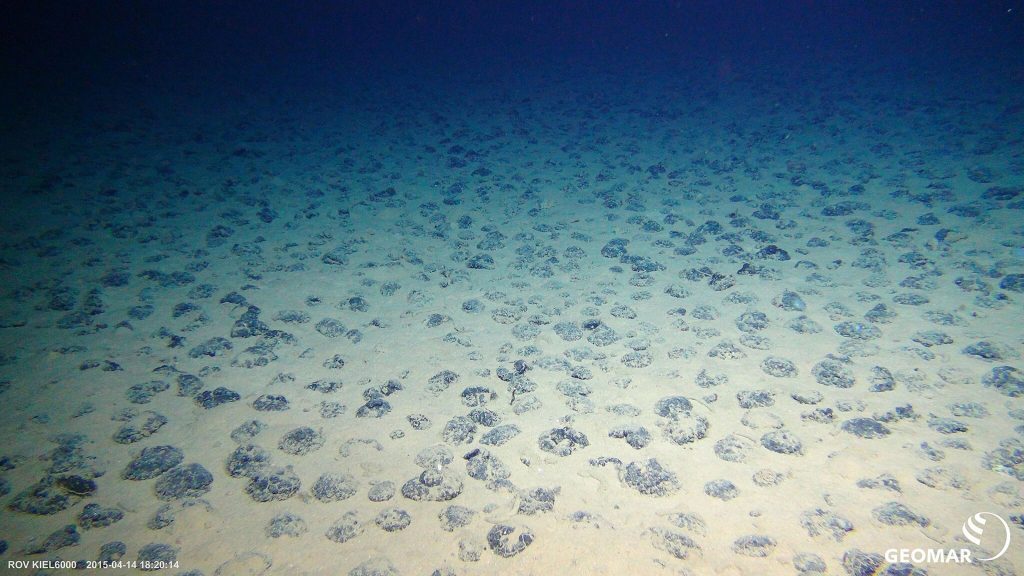

The rules that govern mining on most of the world’s seabed are no ordinary rules. They got their start back in the 1970s and 1980s, when it looked as if there were untold riches in manganese nodules scattered across the ocean floor.

Although that didn’t pan out, mining companies and nations around the world are eyeing anew the riches of the deep. The more recent discovery of metals at hydrothermal vents rekindled interest in the seabed, said Porter Hoagland of the Marine Policy Center at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). “Technology makes it more possible, and the economics make it more likely.”

To regulate seafloor mining, in 1994 the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea spawned the International Seabed Authority, or ISA, an independent treaty organization. It has jurisdiction over the seabed outside the exclusive economic zones that surround nations’ shorelines—an area it efficiently calls The Area. The term refers only to the seafloor, not to the waters above it (they’re called the “high seas” in legal parlance). The rules dictate that the ISA make licensing decisions and, remarkably, that a portion of all profits from mining in The Area be used to benefit the world’s developing countries.

An ISA working group—which includes academic, government, and industry experts for advice on environmental and economic issues—is developing specific regulations, said ISA Secretary-General Nii A. Odunton. “But we could use the international science community to get more information,” he told a gathering of almost 100 scientists from 20 countries and other seabed mining stakeholders at a conference in April 2009 at WHOI. "The more we can get scientists to help us get the information we need, the better we think our regulations will be."

The ISA has 162 member nations as of May 2011. The United States is not one of them, because it has not ratified the Law of the Sea treaty, though it has observer status. The new ISA regulations are expected to open up The Area to commercial prospecting for seafloor minerals.

Meanwhile, in 2010 the industry-sponsored International Marine Minerals Society finalized a voluntary environmental code of conduct for seabed mining. "The code is voluntary, but it will likely be the only international instrument (to regulate seafloor mining) for a while and will likely be the framework for an eventual international legal framework," Philomene Verlaan, an attorney and oceanographer at the University of Hawaii and the society’s environmental code coordinator, said at the April 2009 conference.

Beyond the seabed, all sorts of international, governmental, environmental and scientific organizations have been working on how best to conserve the oceans’ resources. "The deep and high seas are now on everyone’s agenda," Jeff Ardron, director of the Marine Conservation Biology Institute’s High Seas Program, said at the April WHOI conference. "But talking to one another, with all due respect, has barely begun."

One example of the fractured nature of ocean management is the lack of governance of bioprospecting—the hunt for life that can be exploited commercially. It seems that under current rules, which were written to cover mining and fishing, even if one company must have a license from the International Seabed Authority for mining a particular site (and must share the profits), another company can remove some of the site’s microbes, discover it has reaped the cure to cancer, and keep all the money it makes.

And that’s not as far-fetched as it may seem. Biochemical properties of organisms that can tolerate extremes of hot and cold and find nourishment in toxic fluids are of great interest to the biotech industry. Wonder enzymes from organisms at hydrothermal vents are already being used commercially in a variety of ways, from ethanol production to a French skin lotion that protects against damaging free radicals.

—Lisa W. Drew (revised March 2012)