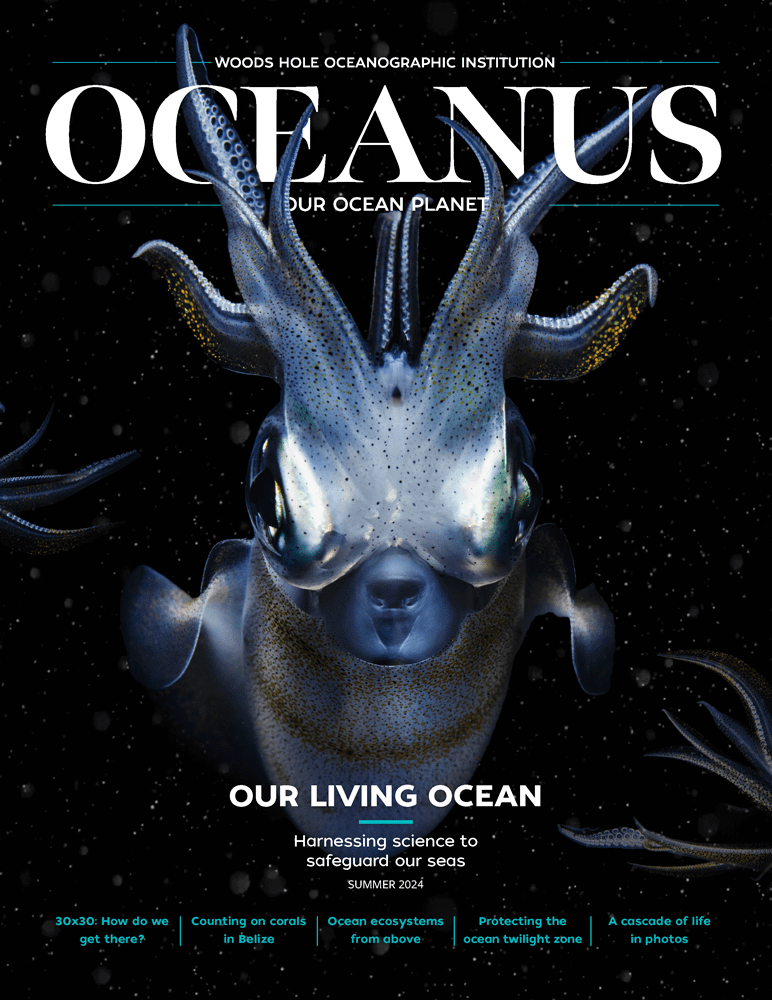

Counting on Corals

As struggling reefs put a squeeze on Belize’s Blue Economy, could heat-tolerant corals be the answer?

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2024

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2024

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

A white vented crate the size of a laundry basket rests on Daniel Palacio’s 23-foot Mexican-built skiff. On a good day, the crate might brim with Caribbean spiny lobsters inside. But today, it’s filled with nothing but sunlight.

It’s well past lunchtime in the central lagoon of Turneffe Atoll, the largest and most biologically diverse coral atoll in Belize. Palacio, who is 25, along with his little brother Deaton and friend Dajon Anderson—also in their 20s—have been idling languidly in their weather-beaten skiff since 8:30 AM without a single catch.

“We’ve rarely seen any lobster,” Palacio says as Anderson, garbed in a wet suit, fastens his scuba mask to get ready for another dive. “There’s nothing in the shades and nothing in the traps.” He pauses for a moment and then blurts out, “We don’t know where they’re going, mon. No one knows!”

The comment sends the trio into a group cackle, a brief reprieve from the weight of their troubles. Then, Palacio’s tone darkens.

“I have a family that I need to provide for,” he says. “I’ve had some trouble making ends because we’re not finding the product [lobster].” Recently, Palacio has been late with his rent due to lost income. “And the product we do find to harvest is to clear the expense, so we barely have anything for ourselves.”

Bleeding white

Spiny lobster is one of several target species for many of the 1,300 commercial fishers around Turneffe Atoll, a 360,000-acre marine reserve off the coast of Belize that comprises general-use and no-take zones. But over the past decade, the crustaceans in this Central American paradise have become difficult to harvest. It turns out, many of the once-vibrant reefs that protect spiny lobsters from sunlight and predators have withered into spectral skeletons owing to a warming ocean. As their shelters bleach and crumble, the lobsters migrate to deeper waters, making it difficult and even impossible to harvest them for freedivers like Palacio.

“We only dive down between 15–25 feet,” he said, “so any lobsters that go deeper are out of reach.”

The tropical seas of Belize have been warming over the past decade and show no signs of simmering down. In May 2023, a massive ocean heat wave, fueled by the Pacific El Niño, swept across Belize’s reef tract, an almost 200-mile (321-kilometer) stretch of barrier reefs and atolls. The water, which flirted with 90 °F (32 °C), stayed hot until late fall. This led to widespread bleaching, which occurs when stressed corals expel their symbiotic algae—known as zooxanthellae—from their cells, causing the corals to lose their color. Anne Cohen, a WHOI scientist world-renowned for her research on coral reefs, bore witness to the event.

"We’ve rarely seen any lobster. There’s nothing in the shades and nothing in the traps."

— Lobster fisher Daniel Palacio

“We were in Belize for a stakeholder workshop and went snorkeling on different reefs across the country,” said Cohen. “In some areas, all the coral colonies were stark white from bleaching.”

In recent years, the waters bathing Belize’s reefs have reached bleaching temperatures earlier in the summer and the events have tended to last longer. But according to Valdemar Andrade, executive director of the Turneffe Atoll Sustainability Association (TASA), a non-profit conservation group based in Belize City, these longer periods of thermal stress are exacerbating other localized pressures on reefs that have been in play for a long time.

“We have other stressors like overfishing and high-intensity hurricanes that pass through,” said Andrade. “There are a lot of factors, so we need more financial support and capacity for the country to work on reef health—looking at what is already protected and identifying areas to raise the level of protection as it relates to reefs. It’s part of meeting the [United Nations goal] of 30% protection of the ocean.”

Survival of the fittest

Like many tropical countries, Belize counts on its reefs—a lot. Hundreds of thousands of Belizeans rely on reefs for survival, according to the World Wildlife Fund, and reefs there provide critical habitats for thousands of marine species. They act as guardians of the coastline by protecting it from storms. And, they contribute roughly $300 million to the country’s economy.

Understandably, fishers are frustrated with the deteriorating reef conditions. And it’s not just young guys like Palacio. Older, more seasoned fishers like Dale Fairweather, who still dives Turneffe for lobster in his mid-60s, are having a tough go.

“The bleaching has had a huge impact on my business. The lobsters have become undependable,” said Fairweather.

The May 2023 bleaching event was particularly tough and caused widespread loss in coral cover throughout Belize. As Cohen snorkeled the reefs, it was also an opportunity to identify which coral communities were not bleaching—those resilient enough to survive the Jacuzzi-like temps.

“As we explored the reef, we began to see fields of healthy, tan-colored corals amongst the ghostly white ones,” said Cohen. “This is what we were looking for.”

The hunt for resilience

Finding the “survivors” is the premise of a research initiative called Super Reefs, which Cohen co-founded with colleagues from The Nature Conservancy and Stanford University. The aim is clear: to find, study, and help protect heat-resistant corals across the tropics.

Cohen and her team have been healthy-reef hunting around the tropics over the last decade and have already discovered reefs that are not just living, but thriving, in the chronically hot waters of Palau, the South China Sea, and other parts of the Pacific.

“Based on observations and evidence from some of the sites we’ve studied, we know there are certain environmental conditions, like chronic heat and high-frequency variability, that can facilitate heat tolerance in corals,” said Cohen.

She and the Super Reefs team utilize physiological and genomics methods to find heat-tolerant coral communities and to better understand the environmental conditions that facilitate heat tolerance. They construct fine-scale hydrodynamic models that simulate reef temperatures with meter-scale resolution to help predict where other heat-tolerant communities are likely to be found.

Now, they are applying these same techniques in Belize. Cohen said the country, like other coral reef nations, is defenseless when it comes to staving off rising ocean temperatures.

“They can’t just build a wall around their reefs to protect them from the next heat wave,” she said. But countries can, she said, work to find the most thermally tolerant coral communities and use that information to ensure they’re included in the new marine protected areas being designed for the country ahead of 2030.

“Belize is pretty special in terms of the level of engagement among government agencies, local NGOs, scientists, and fisheries, which oversee all of the main protected area designations,” said Cohen. “There’s a real diversity of interest groups and stakeholders that are invested in sustainable reef management, which includes ensuring that thermally tolerant corals can survive, reproduce, and restore the country’s reefs.”

A not-so-blue economy

As the researchers set their sights on a brighter future for Belizean reefs, fishers like Daniel Palacio continue to struggle. He and his crew eventually pulled up some lobsters later that day in Turneffe’s central lagoon, but only 10 lbs. worth. The next day was worse—just 5 lbs. over an eight-hour day.

“It was way easier in the past,” he said. “We could dive for like five hours and catch 40 lbs. for the day or more.”

The surging cost of living hasn’t helped. Inflation in Belize has risen 100% since COVID, while lobster prices have plummeted. Just two years ago, Palacio and other lobster fishers were getting $39 per pound. Prices today have fallen to $25 per pound.

And the ailing reefs aren’t just a fishing problem—they’ve caught up with the tourism industry as well. In Belize, tourism pulls in roughly $150 million a year due to the hordes of visitors eager to see of the kaleidoscope of life below the surface.

Karim Fuller, an underwater tour guide based in Belize City, said coral bleaching is, in certain cases, making it difficult for him to give his customers the awe-inspiring experiences they’re looking for.

“As a tour guide, my job is to lead underwater tours and point out stuff,” said Fuller. “That’s kind of hard to do is there’s not much to see. It’s kind of like sending a carpenter to do a job without a hammer.”

Alex Motus, general manager of the Dive Haven Resort on Turneffe Atoll, said that while the resort is working hard to sell Belize as the diving destination, guests may start to think twice.

“People come here to see the vibrant corals,” said Motus. “The bleaching entirely kills the color and your experience of being down there. That could drive guests away to other locations like Roatan or Cancún.”

“These could eventually be the parents of future reefs in Belize when they release billions of heat-tolerant larvae during spawning season.”

— WHOI associate scientist Anne Cohen

A new reef reality

While fishers and tour guides try to navigate their new reality in Belize, the WHOI Super Reefs team, including biologist Simon Thorrold and physical oceanographer Gordon Zhang, is developing simulated models of the reef environment to help identify potential locations of the country’s most heat-tolerant corals. The meter-scale, three-dimensional models guide the scientists to areas of chronically-high heat relative to surrounding waters, as well as those characterized by high variability. The team has provided initial outputs from the model to Super Reef project collaborators in Belize and at Stanford to guide thermal tolerance testing later this year.

Steve Palumbi, a marine ecologist and professor at Stanford who leads the Super Reefs team there, said the models “up the efficiency of the project by an order of magnitude” by providing GPS locations of reefs that are suspected to have a high heat tolerance.

This summer, Palumbi and his team will clip tiny coral fragments from the reef sites and place the samples into a heat tank. There, the corals will be exposed to water temperatures of 89 °F (32 °C) and beyond for several hours a day.

“It’s like a cardiac stress test for corals,” said Palumbi, who describes the cost-effective experimental heat tank as an Igloo beer cooler tricked out with aquarium heaters and pumps. “The tests will allow us to determine who bleaches at what point and will give us a ranking of which corals are the most heat resistant.”

Cohen and her team will conduct benthic surveys and skeletal sampling at the same location as the heat tank testing, and together with TNC and Stanford, they will compile all the evidence together to identify Super Reef locations. Ideally, Cohen said, the team will identify multiple Super Reef areas across the Belize reef system. A subset of high-priority Super Reefs will then be chosen based on results of larval dispersal simulations, which leverage WHOI’s hydrodynamic models. High-priority Super Reefs are not only heat tolerant, but are also able to reseed neighboring reefs.

“These could eventually be the parents of future reefs in Belize when they release billions of heat-tolerant larvae during spawning season,” said Cohen.

From super to digital

The team will begin providing this information to the Belizean authorities later this year to help guide the country’s expansion of marine protections. Longer term, Cohen and her team plan to make their coral reef models and data accessible to reef stakeholders, including tour operators, NGOs, government agencies, and scientists, via a platform called Digital Reefs. It will allow stakeholders to visualize the living, breathing reef in four dimensions using an interactive interface from their computers.

“The technology makes complex, yet enormously valuable, scientific data and models accessible and actionable to decision-makers who may not otherwise use them,” Cohen said. “In doing so, it empowers them to evaluate the outcomes of proposed management decisions in the virtual reef before implementing them in the real world.”

Conceptually, the technology will be easy enough for fishers like Daniel Palacio to use. That is, if he doesn’t give up on the struggling lobster fishery. He’s only in his mid 20s, still young and spirited, so there’s plenty of time for him to pursue other career paths. But despite the challenging conditions, he still seems committed.

“I have hope that the lobster industry here develops sometime soon,” he said. “I have plans to fish the atoll for many more years.”