An aquatic outbreak

Stony coral tissue loss disease continues devastating Caribbean reefs. Here’s what we know about it so far

Estimated reading time: 2 minutes

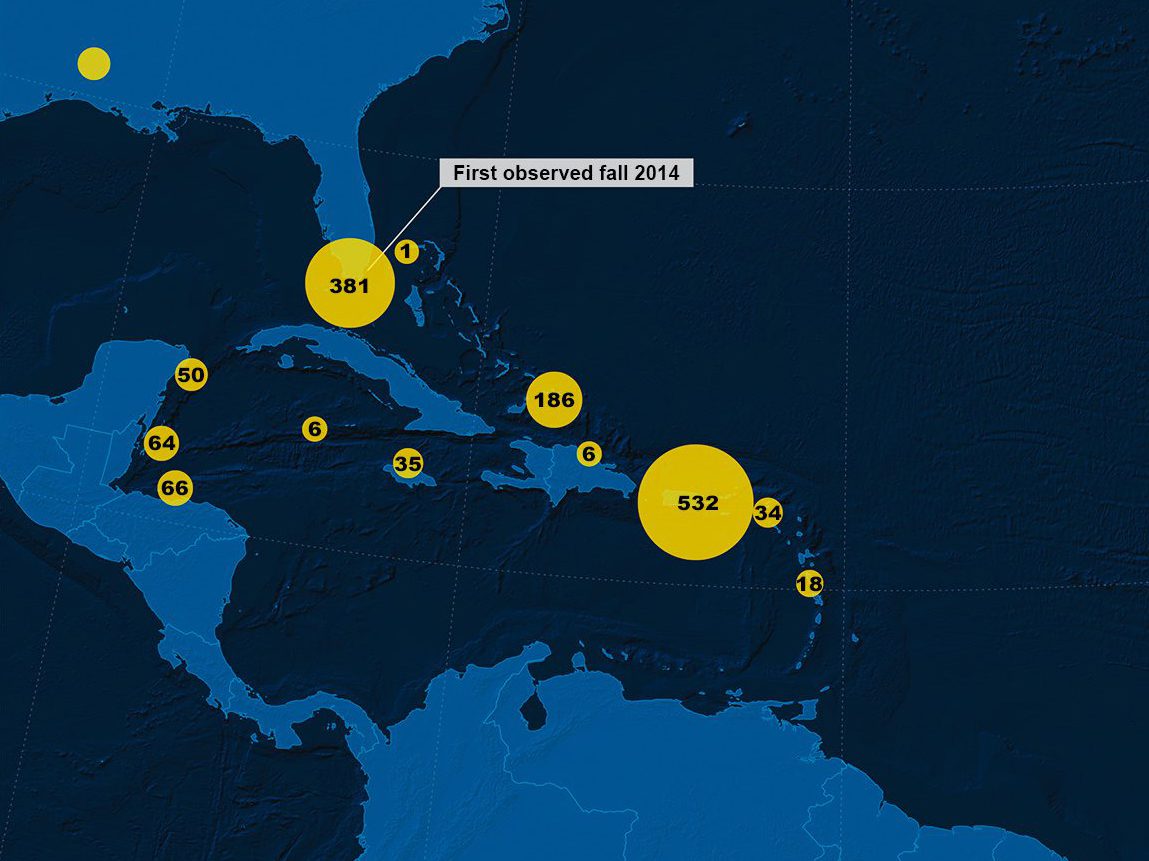

In 2014, a frighteningly lethal disease among the reefs near Miami-Dade County, Florida, began to garner attention. With unprecedented speed, it swept over huge swaths of coral, leaving behind dead, liquefied tissue and algae-covered skeletons in its wake. Before many scientists could confirm its name or origin, it began to appear further south, and within five years, made an appearance along many Caribbean islands and territories below the panhandle. It is known as stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD).

A time series shows the swift progression of stony coral tissue loss disease on a boulder brain coral colony (Colpophyllia natans) in the U.S. Virgin Islands. (Photo courtesy of Sonora Meiling, © The University of the Virgin Islands)

Since the illness was first observed, more than 30 reef-building (scleractinian) corals have been identified as vulnerable. That accounts for nearly 50% of the species found across the Caribbean, many of which are currently feeling the effects. Early research suggests major currents and ballast water taken up and deposited by roaming cargo ships may be prime modes of transportation for the disease, though scientists admit these theories are still in their infancy.

Today, highly susceptible corals have a bleak prognosis, with many succumbing to the disease within a few weeks to a month. This has left a small window of time for responders to intervene.

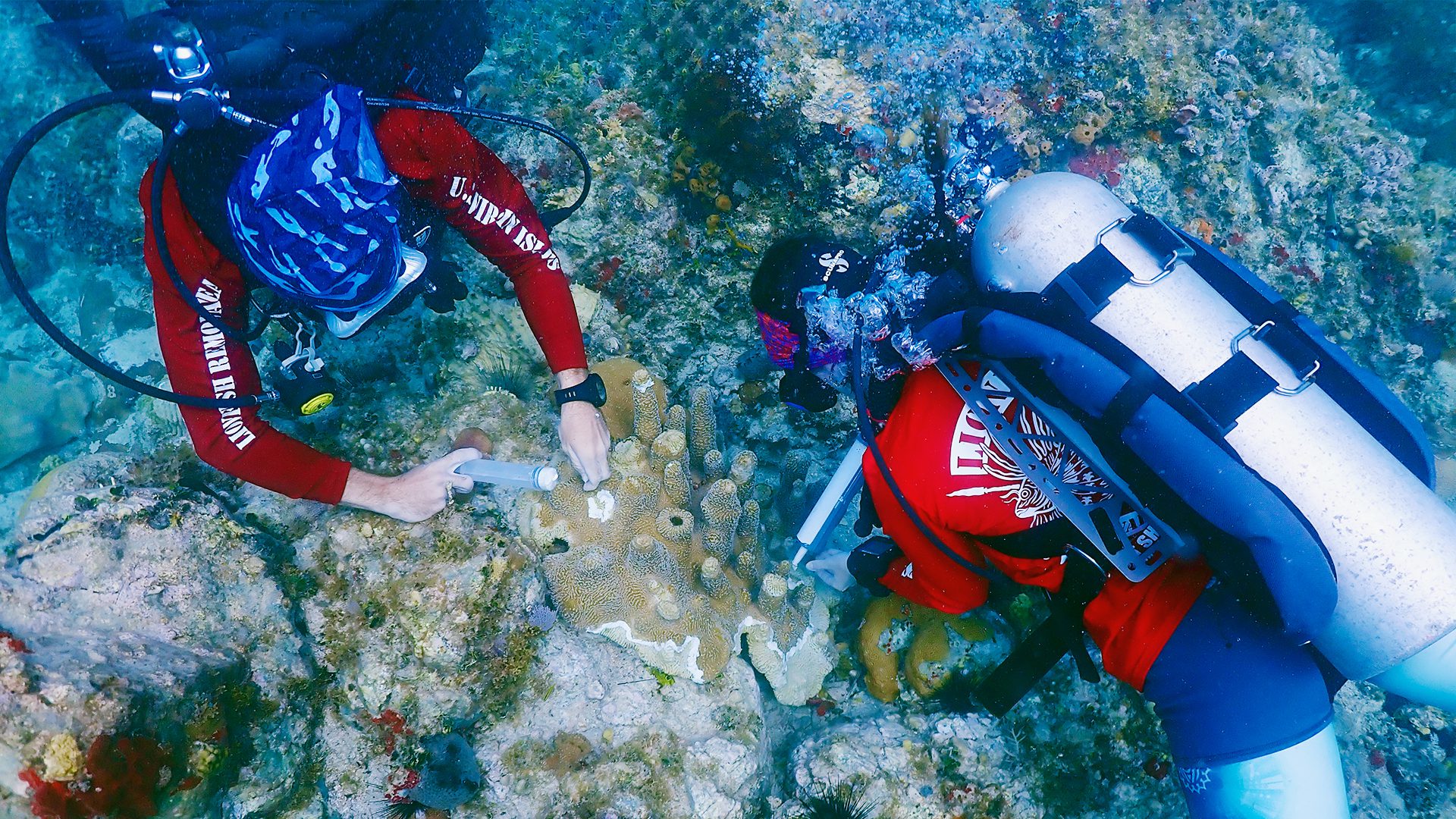

Still, researchers and state authorities at dozens of institutions, including reef scientists with WHOI and its partners at the University of the Virgin Islands (UVI), have mounted an aggressive campaign to track, treat, and contain the disease. In their mad dash, strike teams fragment and cull infected corals and treat them back at laboratories ashore, while others apply underwater antibiotic pastes that mark the microscopic war front between healthy and sick animals.

Left unchecked, SCTLD will compromise not only the homes of commercially and culturally important marine life but also a valuable hurricane buffer for millions of Caribbean citizens.

The map above documents the known whereabouts of the disease as of 2021 and will be subject to an interactive update in 2022. The current illustration is based upon an aggregation of data collected by dozens of institutions since 2017, including those mentioned above. These data have been made available to Oceanus Magazine thanks to the Virgin Islands Coral Disease Advisory Committee, the Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment (AGRRA), and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and its affiliate organizations. They are a reflection of available data and may not include sightings made by other Caribbean island research organizations that are just beginning to track this phenomenon.