Sustainable Ocean

As illegal fishing rages on, is there any hope on the horizon?

Illustration by John Hentz

By Daniel Hentz | JULY 5, 2023

In the grand scheme of the ocean’s health, illegal fishing is not simply an issue. It’s an epidemic.

It’s estimated that nearly 20% of all global fishing harvests are done illegally—a blackmarket industry that costs the international community $10 to $23 billion every year, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts. The problem is so vast that 1-in-5 of the fish humans consume are likely caught through Illegal Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing. For those looking for solutions to overfishing, that 20% represents a gaping hole of unaccounted fishing data, the absence of which is impacting the accuracy of global fish stock assessments and the effectiveness of the regulations meant to help endangered populations rebound.

WHOI economist Yaqin Liu stands on Dyer's Dock in Woods Hole. (Photo by Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

“When we don’t know where and to what extent illegal fishing is taking place, fisheries management is not going to be really successful,” says WHOI economist Yaqin Liu, who works in the Institution’s Marine Policy Center. “So, it’s natural for me to want to do something about this.”

Liu has dedicated over a decade of her career studying environmental economics. In the last two years, she’s assessed the long-term impacts of fishing and climate change on over 700 species to create models that help inform sustainable catch limits. Illegal fishing has been the missing link in her equations, and for good reason—it’s incredibly hard to track.

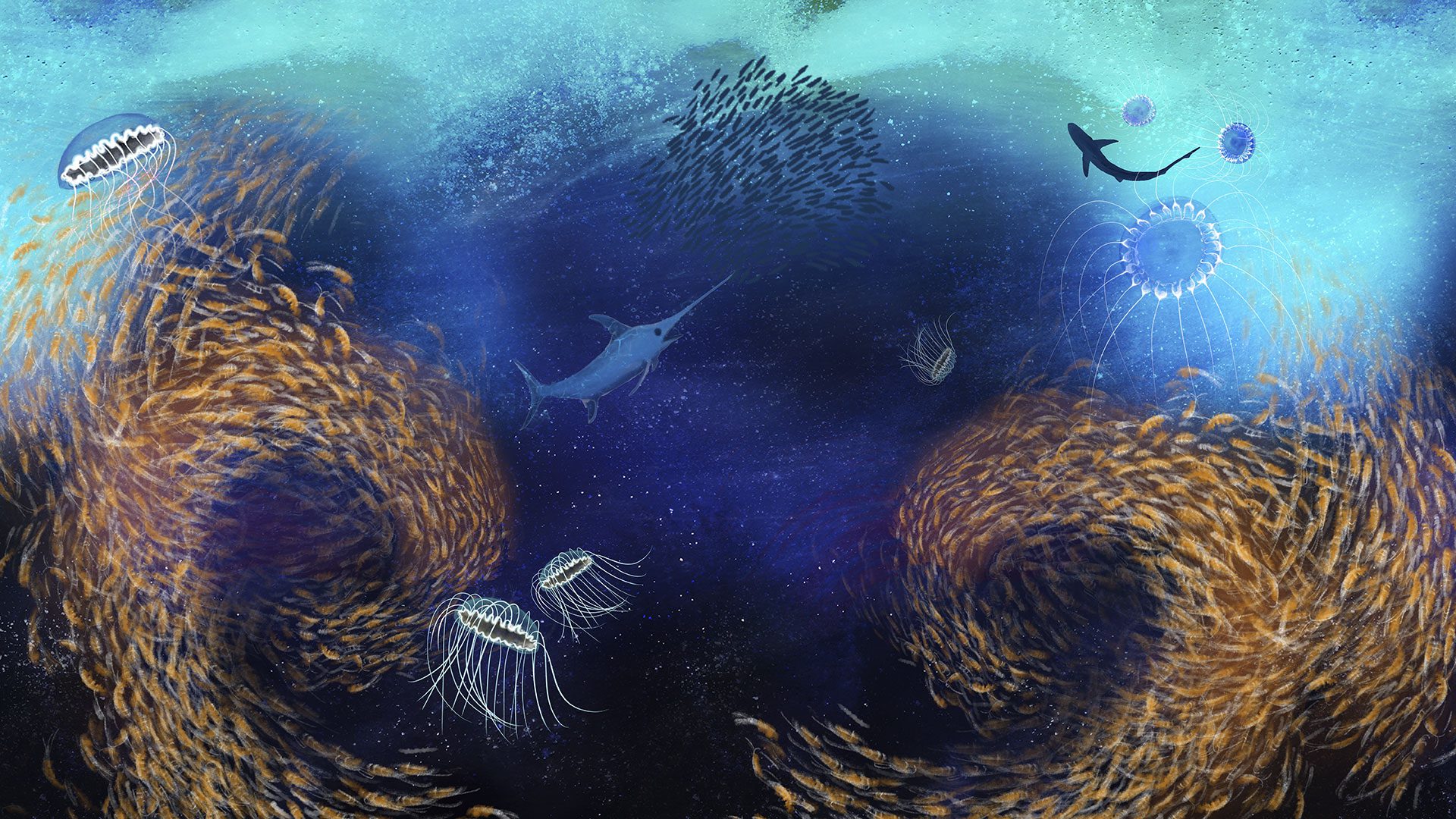

Many culprits evade coastal police by turning off their vessel identification number (or AIS in most western countries), a GPS system initially designed to prevent ships from colliding with one another. Others have started using false coordinates to mislead local authorities on their exact whereabouts while they skim marine protected areas for high-value species. What they all have in common is they continue to put pressure on commercially overfished species, such as mackerel, jack, and anchovy, to name a few.

Perpetrators can range from the subtle—fishermen that use illegal gear, such as driftnets—to the dramatic ones who drive unregistered, rattletrap vessels run by overworked foreign crews.

Consensus to crack down on offenders seems to have grown among world leaders in the last few decades. In March, the United Nations passed the “High Seas Treaty,” which both designated open ocean areas beyond national boundaries as new marine protected zones, and outlined a code of conduct for deep-sea fisheries. Progress on enforcing these fisheries agreements, on the other hand, has remained stagnant without sufficient monitoring tools.

“Even if all the nations of the world agree to create large marine protected areas in the high seas, how are you going to enforce this?” says Liu. “The policy can’t just stay on paper, you need to have practical ways to make sure it’s going to work.”

In lieu of expanding expensive Coast Guard units, most countries will need to rely on satellite data and monitoring tools from organizations like Global Fishing Watch. But while these programs provide a comprehensive look at maritime traffic, they rely heavily on GPS data from these vessels—those ship identification (AIS) numbers mentioned above. Because of this, not many programs are able to track illegal ships that have “gone dark” by turning off their GPS transponders.

Hope to improve these systems, however, may lie in automation.

At WHOI, Liu and a team of engineers and researchers passionate about mitigating illegal fishing are looking into testing the use of artificial intelligence to account for data gaps created by criminal activity. By feeding a computer algorithm with databases of illegal fishing vessel images and descriptions, they hope to teach it how to identify illegal vessels through high-resolution satellite feeds in real time.

If it works, she says, they will be able to create a program that can codify the characteristics of illegal vessels, possibly notifying local coast guard patrols with SMS alerts on their phones in the not-too-distant future. To find hope that such a project could work, she adds, you need look any further than the progress of marine mammal tracking tools.

“There are examples of good machine learning everywhere that use satellite images to detect whales in the ocean, which are much smaller than the vessels we’re trying to detect,” says Liu. “I think that’s promising for the work we’re doing.

“I think if we can make this happen, it’s going to change the world.”

An illegal driftnet nearly 8-miles-long seized by the Sicilian Coast Guard. (Photo courtesy of Alessandro Bocconcelli)

The AI-based project referenced in this piece, “Seeing the Unseen: Tools for tracking illegal vessels at sea,” is currently led by a team of private investigators at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, including Yaqin Liu (Assistant Scientist, Marine Policy Center), Tom W. Bell III (Assistant Scientist, Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering), Daniel Zitterbart (Associate Scientist, Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering), Lee Freitag (Principal Engineer, Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering), Austin Greene (Postdoctoral Investigator, Marine Chemistry & Geochemistry), and Alessandro Bocconcelli (Emeritus Research Scholar, Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering).