Floats Reveal Unknown Ocean Pathways

The North Atlantic's circulation is more complex than previously thought

Oceanographers have long known that the image they used to portray the oceans’ global circulation—called the Ocean Conveyor—was an oversimplification. It’s useful, but akin to describing Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony as a catchy tune.

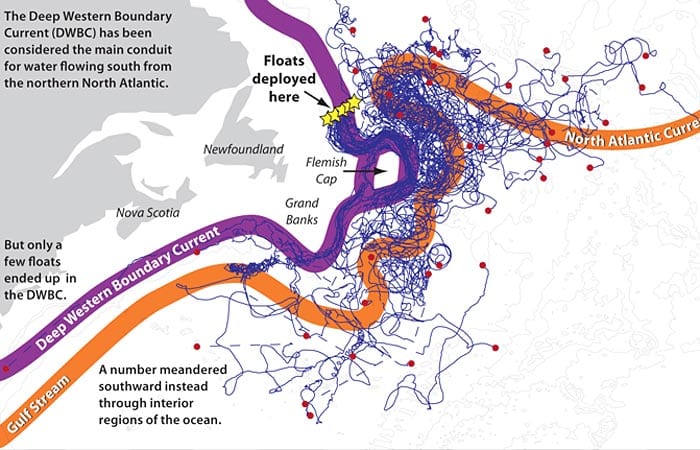

The upper part of the Ocean Conveyor is comprised of warm surface waters from the tropics that are pulled northward along the Gulf Stream. As they head north, these waters release heat to the atmosphere, becoming colder and denser. These denser waters sink into the lower part of the conveyor and reverse direction, flowing southward along the “Deep Western Boundary Current,” which hugs the North American continental slope from Canada to the equator. To replace the waters flowing down, more Gulf Stream waters are pulled north.

Now, researchers led by physical oceanographers Amy Bower of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and Susan Lozier of Duke University have teased out new and surprising intricacies in the symphony of global ocean circulation. In a study published May 14, 2009, in the journal Nature, they show that much of the southward flow of cold water from the Labrador Sea does not move along the Deep Western Boundary Current, but along previously unknown pathways in the interior of the North Atlantic Ocean.

“This new path is not constrained by the continental shelf—it’s more diffuse,” said Bower. “It’s a swath in the wide-open, turbulent interior of the North Atlantic and much more difficult to access and study.”

That complicates matters for climate change researchers seeking to understand the ocean circulation’s large influence on Earth’s climate.

“This finding means it is going to be more difficult to measure climate signals in the deep ocean,” Lozier said. “We thought we could just measure them in the Deep Western Boundary Current, but we really can’t.”

Lozier and Bower developed an elaborate project involving the building of 76 special Range and Fixing of Sound (RAFOS) floats by engineers at WHOI. The floats were launched into the current south of the Labrador Sea from 2003 to 2006. The ambitious program would have been prohibitively expensive without a collaboration with Eugene Colbourne of the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Centre in St. Johns, Newfoundland. Colbourne, who regularly conducts hydrographic surveys around the Grand Banks, agreed to deploy six of the team’s RAFOS floats every three months for three years.

The RAFOS floats submerged 700 or 1,500 meters deep into a layer of cold water called Labrador Sea Water, which originally sank from the surface of the Labrador Sea. It is one constituent of the dense North Atlantic waters that sink and eventually flow south.

The floats drifted with the currents for two years, recording their locations as well as temperature and pressure measurements once a day. After two years, the floats returned to the surface and transmitted all their data via satellite to scientists in the lab.

Only 8 percent of the RAFOS floats followed the Deep Western Boundary Current, or DWBC—“a remarkably low number in light of the expectation that the DWBC is the dominant pathway for Labrador Sea Water,” the researchers wrote in Nature. About 75 percent of them “escaped” that coast-hugging deep underwater pathway and instead drifted into the open ocean before rounding the Grand Banks.

Lozier, her graduate student Stefan Gary, and German oceanographer Claus Boning also used a modeling program to simulate the launch and dispersal of more than 7,000 virtual “e-floats” from the same starting point.

“The new float observations and simulated float trajectories provide evidence that the southward interior pathway is more important for the transport of Labrador Sea Water through the subtropics than the DWBC, contrary to previous thinking,” their report concluded.

The National Science Foundation supported this research.

Slideshow

Slideshow

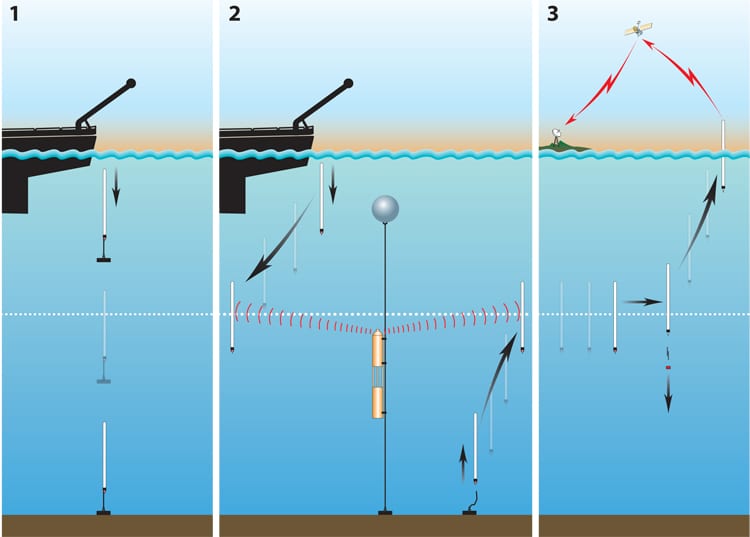

RAFOS floats are designed to take measurements of temperature, salinity, and pressure in layers of ocean water at any depth.They are deployed using one of two methods. Some floats are attached to a small anchor and dropped over the side of a research vessel (left). They sink to the bottom and remain there, in a dormant state, until a preprogrammed time when they release the anchor and rise up to their target depth to start their drifting mission.

RAFOS floats are designed to take measurements of temperature, salinity, and pressure in layers of ocean water at any depth.They are deployed using one of two methods. Some floats are attached to a small anchor and dropped over the side of a research vessel (left). They sink to the bottom and remain there, in a dormant state, until a preprogrammed time when they release the anchor and rise up to their target depth to start their drifting mission.

After completing their drifting mission, these floats release a second weight and rise to the sea surface, where they transmit all their stored data to orbiting satellites which then rebroadcast the information to ground stations (right).

Most floats however begin their drifting missions immediately after deployment from a research vessel or ship of opportunity (middle). At the end of their drifting mission, they also transmit the data they collected to satellites that relay the information to the scientist. (Illustration by Jayne Doucette, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)- WHOI physical oceanographer Amy Bower prepares a RAFOS float for launch from the research vessel Oceanus during a study of the Deep Western Boundary Current in 1995. (David Fisichella, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.)

- Susan Lozier, professor of physical oceanography at Duke University (left) and Ana Rappold, a Duke graduate student at the time, prepare to launch an expendable bathythermograph, or XBT, on a 2003 cruise aboard the research vessel Oceanus. The XBT collects measurements of water temperatures at depths within the ocean. (Photo by Jaime Palter, Duke University )

Related Articles

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Interior Pathways of the North Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation from Nature magazine

- Export Pathways from the Subpolar North Atlantic Research project description

- RAFOS floats from WHOI Ocean Instruments Web site

- Amy Bower

- Susan Lozier

- Line W Monitoring the North Atlantic Ocean's Deep Western Boundary Current