The future of the ocean’s conveyor belt

By Evan Lubofsky | February 18, 2020

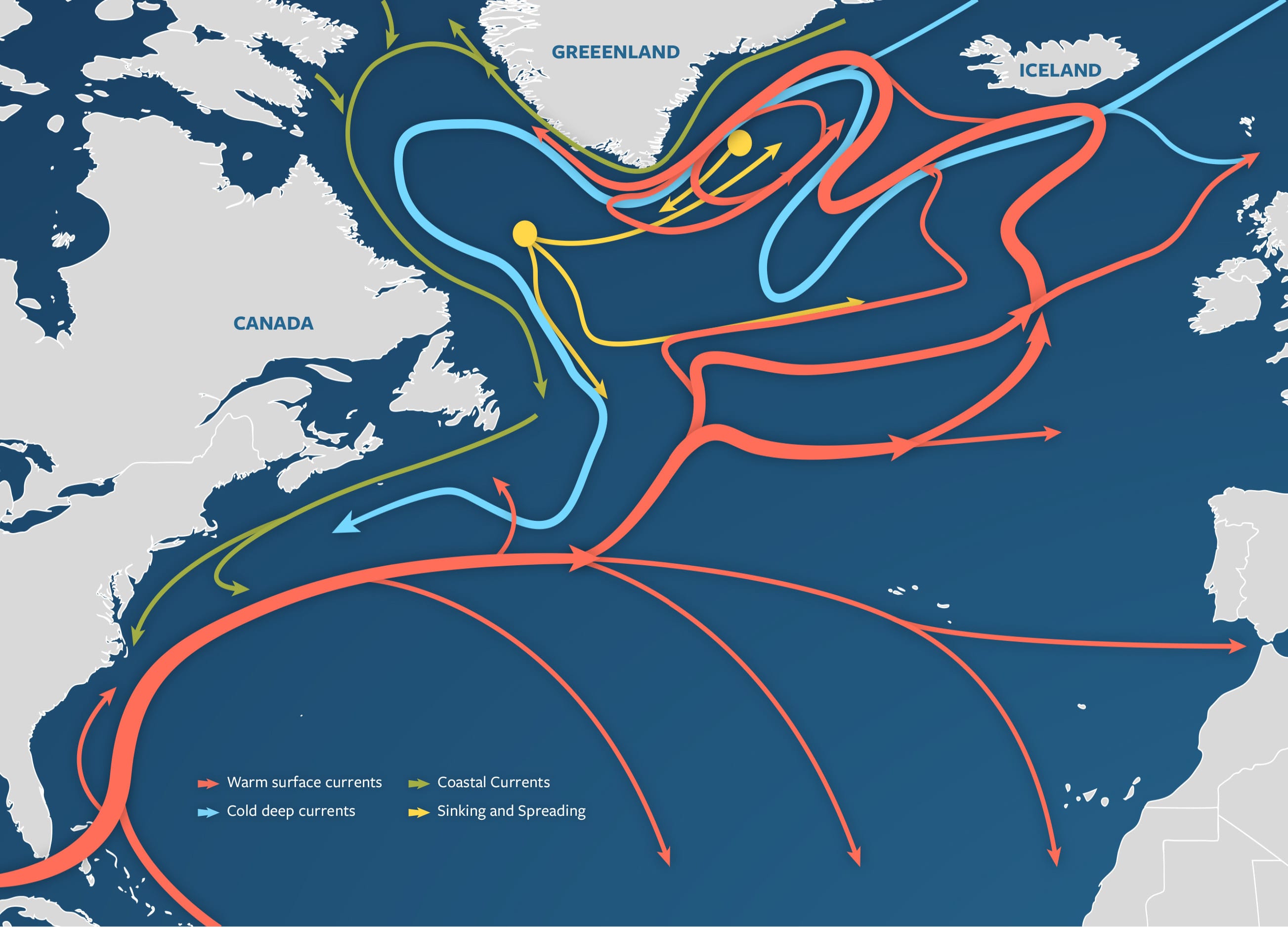

Young-Oh Kwon arrived at WHOI in 2006 with a strong background in climate modeling, and a particular interest in natural variability of the ocean. It was a perfect blend for studying the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)—a conveyor belt of currents that move warmer waters north and cooler waters south in the Atlantic Ocean. We caught up with Kwon to get his perspective on the state of this critical ocean circulation system and changes we may see in the future.

Why is an understanding of the AMOC so important?

The AMOC is a driver of how heat is distributed throughout the ocean, and one of the very basic components that regulates Earth’s climate. That means that if the AMOC varies, our climate will be affected. For example, if the system strengthens or slows down and thus more or less warm water gets to the North Atlantic than usual, it could cause erratic weather patterns or storms. My recent study suggests if the AMOC strengthens and more warm water is pushed north, it can lead to extended periods of high pressure systems in the North Atlantic and northern Europe that cause droughts.

Long-term forecast information can, and should, come from the ocean. So it’s important that we study the state of how the ocean’s major circulation system is working.

AMOC activity is notoriously difficult to track, according to many ocean scientists. Why is that, and more importantly, what can be done about it?

We know the AMOC is very difficult for climate models, which don’t do well at simulating things like eddies. So, climate models need to be improved a lot in order to tell what’s going to happen 100 years from now. One important question right now is: How do we improve the models?

That’s where observation data comes in. Instruments like profiling moorings in the OSNAP array measure the ocean to help us understand the essential ingredients that runs the AMOC and how natural variability in the ocean and climate change is impacting it. There’s a limited amount of observation data available for AMOC studies, so it’s important that we have sustained monitoring efforts in order to have longer records of what’s happening.

Another tool that may help us better understand the system is machine learning. A lot of people in the community talk about the potential use of machine learning to help connect observation data and models, and figure out where models can be improved upon based on data collected in the ocean. That’s a very promising and exciting area.

Is the AMOC showing a weakening or strengthening trend, and what do you expect to see in the future?

Current-generation climate models project that the AMOC will continuously slow down towards the end of 21st century, and this was reflected in the latest IPCC report on climate change. From my perspective, the system is still on a gentle slope and we haven’t seen the rapid decline that some models are suggesting. However, it is likely going to eventually decrease. But by how much remains a major question.

One thing I can guarantee is that the main drivers of changes in the AMOC over the next 10 years will be different than they will be in 100 years. The changes over the next decade will be dominated by the natural variability that occurs in the ocean. But looking out over the next century, climate change will likely be the dominant signal.

In either case, we need to continue learning about the underlying components of this important system and how the various factors work to increase or decrease its strength.