From Penguins to Polar Bears

The impacts of climate change in polar regions

As air and sea temperatures rise, the United States and other nations are experiencing more and bigger storms, droughts, and wildfires. But the effects of climate change may be greatest in Earth’s polar regions. In Antarctica and the Arctic, thinner ice is covering less area for a shorter time each year, and that ice loss threatens organisms whose lifestyles depend on it, ranging from algae at the bottom of the food chain to polar bears at the top.

Conservation efforts for polar species, however, are especially challenging. While managing a forest or a fishery might be done at a regional or national level, managing polar zones requires international solutions. Why? Because climate change involves the entire planet, and because polar regions cut across national boundaries, said Stephanie Jenouvrier, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) who studies penguins and other seabirds.

How then can scientists best help policymakers to develop effective conservation strategies for polar species? To explore these issues, Jenouvrier invited climate scientists and biologists, resource managers, policy experts, and artists to WHOI in May 2014. This was the ninth in a series of Elisabeth and Henry A. Morss Colloquia, which bring experts to WHOI to exchange and foster ideas on important issues that confront human society today.

On thinner ice

Many polar species are “ice obligates,” which means they absolutely require sea ice in order to survive, said Scott Doney, director of the Ocean and Climate Change Institute at WHOI.

Polar bears, for instance, rest on large floes between their forays into the sea to capture seals. Without plentiful ice islands, they can’t stay close enough to their rich hunting grounds and may drown in the attempt to swim farther, or starve. Because they evolved for life on ice and at sea, they can’t shift to a terrestrial lifestyle. Restricted to land (where their grizzly, nonseagoing cousins thrive), they struggle to find enough to eat.

Less charismatic species, such as the algae that grow on the underside of sea ice, also suffer when the sea ice goes away—and that affects the entire ecosystem. Under-ice algae feed the krill that support much of the oceanic food chain, including fish, seals, whales, and penguins. With loss of sea ice, the annual bloom of algae shrinks, along with the prospects of all those other species—including the people who rely on polar ecosystems for their livelihood.

Doney added that loss of sea ice also means we will see more ship activity and oil and gas drilling in polar areas, increasing the potential for spills and other environmental impacts in those areas. Finally, he said, the higher carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, primarily from burning of fossil fuels, not only warm the air and water but also cause the ocean to become more acidic, an effect that is especially pronounced in Arctic waters.

The tools at hand

Efforts to protect polar species are under way—some brand-new, and some with help from laws that are decades old. Shaye Wolf, climate science director for the Center for Biological Diversity, pointed out that the United States has laws on the books that can be used to address many problems related to climate change, even though they were not enacted with climate change in mind.

The Clean Air Act was passed in 1970 and helped reduce smog in major cities and acid rain in the Northeast, but more recently it has been applied to climate-changing greenhouse gas emissions. The purpose of the Clean Water Act, passed in 1948, is to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s water” (both fresh- and salt-). That includes acidification of coastal waters, which in many parts of the U.S. are already impaired according to Clean Water Act standards.

Then there’s the Endangered Species Act (ESA), which aims to protect imperiled species and the habitats they rely on. Ninety-three percent of the species listed as endangered under the ESA since 1973 have either stabilized or improved (although few have recovered to the point of being de-listed), said Wolf. “It’s the world’s strongest wildlife protection law.”

Because saving a wild species requires maintaining its habitat, the ESA provides a route to protect areas, such as the Arctic, that are vulnerable to climate-related damage. But it is not a perfect tool, said Lynn Scarlett, managing director of public policy at The Nature Conservancy. While the ESA mandates that listing decisions be based solely on science (and not on economic, social, or political concerns), its language is frustratingly imprecise.

For a species to be listed as “threatened,” for example, its danger of extinction throughout all or a significant part of its range must be “reasonably likely to occur within the foreseeable future.”

“ ‘Reasonably likely, foreseeable future’—what does that mean?” Jenouvrier asked. “My work is to project into the future what will happen for penguins. What kind of time frame should I use? It was very helpful to see how the term has been interpreted in the past, so we can implement a scientific approach that matches the needs of policymakers.”

Local, national, global

Even at their best, U.S. laws are of limited use when it comes to polar protection because they only apply to species and habitats that occur within U.S. territory. Polar bears, the first species to be listed as endangered primarily because of climate-related habitat loss, were eligible for protection under the ESA only because some of them live in the U.S., specifically Alaska, and the legal protections don’t extend to those living elsewhere.

Antarctica presents a special case, because the region does not belong to any one nation or small number of nations, as much of the Arctic does. The activities of scientists, whalers, fishermen, and others who study or harvest its resources are governed—in a very loose sense—by multinational agreement. Participants in the Morss Colloquium heard from several speakers about the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), a treaty established among 24 states, including the U.S. and the European Union, to monitor changes in the Antarctic and manage its resources, particularly fisheries.

Protecting Antarctic species can begin with a strong statement from one member, such as the potential listing of Emperor penguins under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, as Jenouvrier and her colleagues recently called for. At the very least, Jenouvrier said, the U.S. could influence resource use in Antarctica by banning products harvested there, such as krill-derived dietary supplements. Reducing the market for such items could protect krill by making it not worth the expense to harvest them.

Coming together

Like nations, scientists also need to coordinate their efforts, among other reasons, because there are differences among polar “neighborhoods.” Complex air-sea-ice interactions can lead to different climate impacts in different places, WHOI biologist Hal Caswell pointed out. In some parts of Antarctica, sea ice is actually increasing.

Such nuance poses a problem in the political realm, where differing results may be cited without context and portrayed as meaning that nobody really knows what’s happening. But rather than negating an overall conclusion, different circumstances at various study locations that can help illuminate and refine the broader conclusion, he said.

At the colloquium, scientists studying Adélie penguins in colonies all over Antarctica agreed on a common framework for their research that will make it easier to understand why some colonies are crashing and others are thriving. Eventually, said Jenouvrier, gathering comparable information about each colony and its environment will help scientists provide better information to policymakers.

“You really need to use the same tool everywhere to be able to assess the impact of climate change,” she said. “If you use different research tools, how do you distinguish between the impact of the various methods and the true impact of climate?”

Jenouvrier is aiming to establish that approach as a model for research on other polar species that are vulnerable to climate change. Despite the difficulties of doing long-term studies and influencing international policy, she is optimistic about our chances of conserving polar areas and species, in part because of public interest in programs like the colloquium.

“People seem to care,” she said. “And if they care, it’s a way we can change things. I don’t know how long it will take to change, but we can at least develop the science that is good enough to be ready to influence policy.”

The colloquium was supported by a generous donation from Elisabeth and Henry Morss.

Art Amid Science

This year’s Morss colloquium was the first in the series to include an art exhibit. It ran for two weekends at the Community Center in Woods Hole and featured photographs by WHOI research associate Chris Linder and watercolor paintings (such as “One Life,” above) by artist Aurélie Lebrun du Puytison.

“The aim of including an art exhibit was to try to sensitize the public about the impact of climate change,” said the colloquium’s organizer, WHOI biologist Stephanie Jenouvrier. “Sometimes when you say we have already a temperature increase of two degrees, people say, ‘So what?’ They don’t really relate to a few degrees of temperature. If you say, ‘It could endanger penguins and polar bears—they could disappear—people say, ‘Oh, maybe two degrees has a huge effect.’ ”

Jenouvrier had spoken with painter du Puytison many times about her work with seabirds in Terra Adélie, Antarctica, and her concern over the fate of polar species: The artist is her sister.

“I showed her a lot of pictures and talked about my science,” said Jenouvrier. “Then she translated what would show in a graph about population decline as a feeling in watercolor.”

At a public panel discussion before the colloquium began, photographer Linder said that his aim during his expeditions to polar regions is to use his camera to tell the scientists’ stories in a way that will connect with, educate, and inspire the public. He appears to be succeeding.

“I’ve gotten great reactions, especially from kids as young as preschool,” he told the group.

Slideshow

Slideshow

WHOI biologist Stephanie Jenouvrier, seen here holding a young Emperor penguin, invited biologists, climate scientists, conservationists, and policy experts to a Morss Colloquium in May to discuss issues related to management of polar ecosystems. (Photo courtesy of Stephanie Jenouvrier)

WHOI biologist Stephanie Jenouvrier, seen here holding a young Emperor penguin, invited biologists, climate scientists, conservationists, and policy experts to a Morss Colloquium in May to discuss issues related to management of polar ecosystems. (Photo courtesy of Stephanie Jenouvrier)- Jenouvrier led a team of researchers that recently found the Emperor penguin, the world's largest species of penguin, to be "fully deserving of endangered status due to climate change." (Photo by Peter Kimball, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Polar regions are showing greater effects from climate change than any other regions on Earth. One of the biggest impacts is the reduction in sea ice—thinner ice is covering a smaller area for a shorter time each year. The loss of ice threatens organisms whose lifestyles depend on it, ranging from algae at the bottom of the food chain to polar bears at the top. (Photo by Chris Linder, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Algae grow on the underside of sea ice. As ice cover shrinks, so does the crop of algae, which affects all the animals that depend on algae for their sustenance. One of those is krill, the small red crustaceans that are favorite prey of many penguins and whales. Here, evidence of a krill-heavy diet is obvious around the nests of a Gentoo penguin colony. (Photo by Melissa Patrician, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Chinstrap penguins also rely heavily on krill. These chinstraps are panting to cool off on a relatively warm Antarctic day. (Photo by Michael Polito, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- An Adélie parent feeds its chicks. WHOI scientist Scott Doney studies a population of Adélie penguins that has declined precipitously in recent years. (Photo by Chris Linder, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- In some parts of Antarctica, sea ice is actually increasing, due to complex air-sea-ice interactions. While some colonies of Adélie penguins have crashed, others are thriving. Whether the healthy populations are big enough to sustain the whole species is not known, said WHOI biologist Stephanie Jenouvrier. (Photo by Chris Linder, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

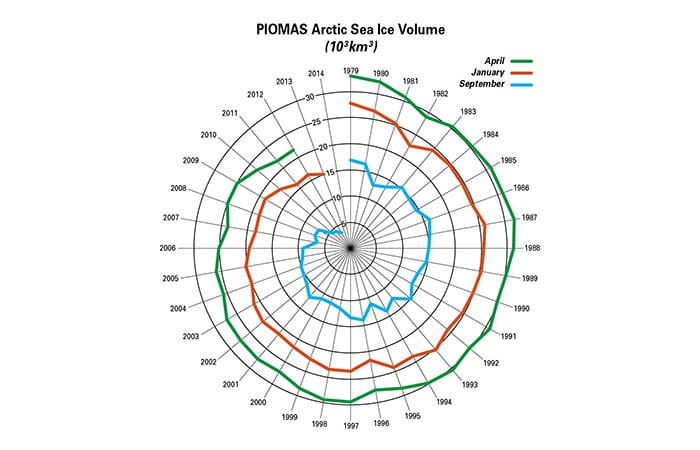

The volume of sea ice in the Arctic has declined sharply in recent decades, as shown in this display. April, which is at the end of the Arctic winter, is still the month with the greatest volume of sea ice, but the total has declined by almost half since 1979. The volume of sea ice in January (midwinter) has dropped by more than half. And in September, at the end of summer, almost no sea ice remains. This graph, sometimes called the "Arctic death spiral," is based on monthly measurements of sea ice from January 1979 to June 2014.

(Original illustration © Andy Lee Robinson, modified by Jack Cook, WHOI)- In addition to supporting algal growth, sea ice also provides resting places for polar bears, which range far from shore in their search for seals. With less ice, the bears may not be able to find enough prey or may not have a place to eat their dinner after they catch it. (Photo by Carolina Nobre, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Forced to swim longer distances in search of food, polar bears may not survive. They are supremely adapted to life in an icy sea and a rich diet of seal meat and do not do well if confined to land. (Photo by Mary Carman, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- At the Morss Colloquium, WHOI biologist Hal Caswell spoke about the difficulty of predicting the exact timing and extent of events such as catastrophic loss of sea ice or the crash of a polar bear population. However, he said, uncertainty about specifics does not mean the overall conclusion is wrong—although it is sometimes portrayed that way in the political realm. (Photo by Jayne Doucette, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Caswell told the audience at the Morss Colloquium about attempts to predict the fate of a population of polar bears along the north coast of Alaska. Ten different models of sea ice extent and bear numbers predict different results for the next few decades, but all show that by the year 2100, sea ice in the area will have declined so much that the polar bear population there, which now stands at 1,500, will not survive. (Photo by Chris Linder, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Photographer and WHOI research associate Chris Linder said he uses photos to tell the stories of polar scientists and to raise awareness of the effects of climate change. An art exhibit held in conjunction with the Morss Colloquium featured several of the images he has captured on 38 expeditions to the Arctic and Antarctica.

(Photo by Benjamin Linhoff, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)- "Insouciance," a watercolor painting by Aurélie Le Brun du Puytison, was part of the art exhibit held in conjunction with this year's Morss Colloquium. Inspired by photographs her sister, Stephanie Jenouvrier, captured during research expeditions, de Puytison created a series of paintings of animals including polar bears, wandering albatrosses, Emperor penguins, and Weddell seals in fading, atmospheric depictions of endangered polar landscapes. (Painting © Aurélie Le Brun du Puytison)

Video

Related Articles

Featured Researchers

See Also

- From Penguins to Polar Bears The 2014 Morss Colloquium

- Stephanie Jenouvrier lab

- Study Finds Emperor Penguin in Peril WHOI news release

- The Decline and Fall of the Emperor Penguin? Oceanus magazine story

- Chris Linder Photographer's website

- Polar Bear Population Likely to Become Extinct WHOI news release

- About the Morss Colloquium