On the crumbling edge

The race to ensure protection for the emperor penguin across the world

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

“You’re hoping they’re still there.”

Peter Fretwell, a geographer with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), spends much of his time scanning satellite imagery taken around the Antarctic coast to keep track of the world’s only emperor penguin colonies. But for three to four months a year, those images are pitch black, shrouded by the shade cast from the Earth’s tilt during the Antarctic winter. When the sun dawns on the continent again in the spring, he can check back on the satellite data to look for the black specks of huddled penguins, or their reddish guano stains. Lately, he’s been nervous to see how these populations will look when the sun comes up.

Climate change has hastened the pace of collapsing ice shelves and seasonal fast ice in Antarctica, which adult emperors need to breed and forage for fish, and chicks need in order to bide time before they can grow their waterproof plumage to swim. It’s also brought anomalous tropical storms further into the Southern Ocean where they haven’t traditionally reached.

In 2010, a West Antarctic penguin colony called Snow Hill was washed over by a freak rain storm, soaking the downy feathers of hundreds of newly hatched chicks and freezing them to death. In 2016, rising temperatures and the untimely dissipation of sea ice caused more than 10,000 chicks to perish in the Halley Bay colony of West Antarctica (the continent’s second largest colony). Later, a 2019 paper authored by Fretwell and fellow BAS biologist, Phil Trathan, confirmed a three-year breeding failure for the same colony.

“Globally, if you want to look at a species which is affected by climate change and where we have the science to show that, the emperor penguin is really the flag-bearer,” says Fretwell.

Today, the collapse of ice shelves once thought to be stable in East Antarctica has scientists even more worried that emperor penguins could be in greater danger of extinction than previously thought. This fear was punctuated by the recent Conger Ice Shelf collapse in March, an event that made headlines after the majority of the area’s 460 square miles crumbled into the ocean in just two days.

“There are lots of other similar ice shelves in Antarctica, which have associated emperor penguin colonies that you have to start worrying about,” says Fretwell. “It really shows that things are starting to change and the Conger Ice Shelf’s collapse is a herald of that change.”

Previously, climate modelers and polar ecologists directed much of their concern to the penguin colonies around West Antarctica. There, much of the continent sits below sea level and is exposed to warmer waters that lap against the ice shelves from below. By contrast, the colder Eastern Antarctic, which sits above sea level, was seen as a more viable refuge for the specie's long-term survival. Now, scientists aren’t so sure.

Just after the Conger’s collapse, temperature readings at the East Antarctic weather stations of Vostok and Bunger Hill measured record high water temperatures—more than 75°F above seasonal averages. For climate modelers, this coincides with more dire predictions if planetary warming is left unchecked.

“We have found that there’s this goldilocks zone of sea ice conditions for penguins to thrive and for their populations to be sustainable” says WHOI quantitative ecologist and penguin expert, Stephanie Jenouvrier. “If sea ice declines at the rate projected under current energy-system trends and policies, almost all colonies would become quasi-extinct by 2100.”

The solution proposed by scientists and environmental advocates is an unsurprising refrain: cut global carbon emissions to slow warming trends and preserve the Antarctic. Because protections for the emperor penguin undoubtedly rely on reducing warming from greenhouse gas emissions, activists have focused on using models from scientists like Jenouvrier to make the case for their endangered status and the protections that would follow.

“We use this analogy of the canary in the coal mine, that if emperor penguins disappear, it will be a bad sign for the stability of the ecosystem itself,” adds Jenouvrier. “The health of the emperor penguin today can indicate that the ecosystem is collapsing.”

The research provided by scientists like Jenouvrier and Fretwell has thankfully swelled in recent years with improved satellite imagery, state-of-the-art models, and funding for Antarctic surveys. That’s bolstered a 15-year-long bid to list the emperor penguin as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act.

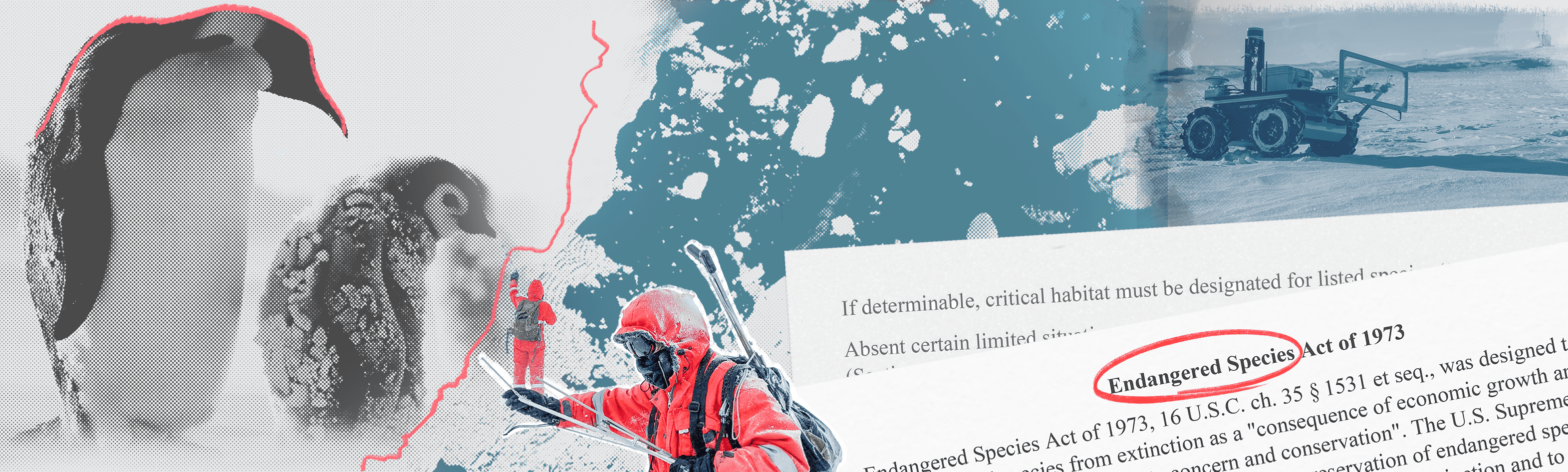

An Antarctic researcher uses antenna to scan individuals for RFID tags at the Atka Bay emperor penguin colony in a blizzard and the setting midnight sun. (Image courtesy of Daniel Zitterbart, © WHOI, Fau Erlangen)

The Path to Protection

Nearly 10,000 miles from the nearest emperor penguin colony, activists with the U.S.-based non-profit, Center for Biological Diversity, have spent years amassing evidence of these threats from research conducted by Jenouvrier, Fretwell, and others. The culmination of this has been species listing petitions made for consideration by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)—the governing body that approves new species listings under Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Petitions by the center began as early as 2006, but Antarctica’s harsh winter temperatures and costly scientific expeditions make it hard to collect the amount of data required by the USFWS to validate the emperor’s ESA status. That resulted in a listing denial in 2008 due to insufficient science and a backlog of other species applications. A 2011 petition suffered a long-delay that ended in no decision by the agency.

“It’s such a loss for the species because in the meantime they’re not getting the protection they deserve,” says Shaye Wolf, director of climate science at the Center for Biological Diversity.

By 2014, a petition by Wolf’s team to list the bird went into a deliberation phase at USFWS until later lapsing the 12-month deadline for the agency to accept or deny the proposal. It wasn’t until August, 2021 that USFWS accepted the center’s proposal, an approval period that is now expected to reach finalization on August 4, 2022 granting the species “threatened status” by law. Wolf and others thank the predictive power of climate models that simulate the penguin’s collapse with sobering detail.

“I brought together climatologists, ecologists and policy experts to provide state-of-the-art projections of the emperor penguin response to climate change to understand whether the listing is warranted,” says Jenourvier. “Under current projections, we concluded that the species should be listed as threatened under the ESA.”

If it passes, the law may give government officials more teeth in regulating carbon emissions produced by other federal agencies, as well as restricting krill fishery activities that overlap with sensitive foraging and breeding sites. More importantly, experts agree the emperor’s ESA status could be a beacon for international allies to add the bird under their own legal protections.

“The hope is this listing could ultimately contribute to reducing carbon pollution worldwide,” adds Wolf. “The U.S. recognizing that the emperor penguin is threatened by climate change and giving it increased status can help positively influence international negotiations that could bring more protection.”

That includes agreements negotiated by international parties like the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCLAMLR) and the Antarctic Treaty, which oversee use of the continent and its resources. At the very least, the domino effect of this ESA status may strengthen the argument for global emissions reductions writ large.

But advocates don’t want to stop with the ESA.

The emperor penguin currently holds a “near threatened” status on the global endangered species inventory, IUCN Red List, something scientists agree needs to be updated. To do that, however, researchers will need to learn more about the specific changes happening to the health of a wider sample size of penguins—something satellites alone can’t provide.

Researchers use ARGOS-datalogger equipment, Tesa-tapes, and Colson-ties to track an emperor penguin fledging chick from Atka Bay. (Photo courtesy of Daniel Zitterbart, © WHOI, Fau Erlangen)

An ECHO across Antarctica

As climate change worsens, and ice shelves collapse in the Antarctic, scientists expect emperor penguins to emigrate to stabler neighboring colonies. Overtime, the frequency of that emigration may indicate the health of the population, something WHOI scientist Daniel Zitterbart is interested in tracking.

“We know emperor penguins move between colonies, but we don’t really know how much they do that,” says Zitterbart.

Sixty-one colonies;

Two-hundred thousand breeding pairs of nearly identical penguins around a continent wider than the United States;

Up to $35,000 just to transport one scientist to Antarctica and back;

And just a few months of sunlight and stable weather conditions to work.

It’s not hard to imagine that penguin scientists dream of an easier way to be on these icy shores year-round without risking their health or depleting their budget. But nano-puff jackets and baked-beans aren’t cutting it when it comes to tracking tagged penguins over longer periods of time.

In the past, researchers used gaudy flipper tags to identify penguins. But they soon realized these created drag in the water, reducing the animals’ chance to hunt successfully. Then came the RFID tags, which use radio frequencies to identify each animal—much like the chips we use to identify our pets when they’re lost. But scientists still needed a way to reliably “see” the animal again to gauge its health—a technique in population studies called “mark recapture.”

“The animals can live in an area that’s several square miles,” adds Zitterbart. “And it’s impossible to fence off several square miles of land and ocean.”

Instead, Zitterbart and his colleague Céline Le Bohec of l’Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien, have developed ECHO, a fully autonomous rover that can use LIDAR and a 360° camera to find penguins and scan their RFID tags even when scientists aren’t there.

Under its parent project, MARE, or Monitor the health of Antarctic maRine ecosystems using Emperor penguins as sentinels, ECHO will use wireless communication with a remote camera-enabled penguin observatory called SPOT that can act as a look-out for colony locations and then instruct the rover to know where to go.

Footage from the UGV ECHO rover's 360° camera and outside the vehicle shows it approaching a group of emperor penguins to scan them for radio tags so scientists can keep track of the animal over time. (Video courtesy of Dan Zitterbart, © AWI, WHOI, FAU Erlangen)

“The Antarctic is lagging behind in studying the impacts of climate change compared to the Arctic and our northern latitudes,” says Zitterbart. “The long-term goal if this project works is to put new SPOTs and ECHOs in locations where we haven’t been.”

In the next four years, Zitterbart hopes to have solar garages that can recharge ECHO and shelter it from passing storms to extend its time in the field. Still, he and his colleagues will need to do the tireless work of tagging 300 emperor penguins each year for ECHO to track.

Eventually, ECHOs findings could help scientists like BAS ecologist Phil Trathan who hope to use the data to elevate the emperor’s status on the IUCN Red List.

We need technology like ECHO to identify individuals as they migrate to other colonies, says Trathan, a penguin specialist on the IUCN Species Survival Commission. “Right now, you can only speculate ten years in advance what will happen to them.”

As ice shelves like the Conger break up and circulate around the continent, their towering iceberg fragments may get caught along the coast, blocking important passage points for penguins that force them to relocate to access food. ECHOs tracking could help scientists better quantify the impacts of these events.

“At the moment these spaces are empty of humans and full of wildlife,” says Trathan. “If they become also empty of wildlife because the environment changes…well, then that’s a bit of a shame.”

Funding for the ECHO rover project comes from the National Science Foundation, with logistics support provided by the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, and institutional support from WHOI and FAU Erlangen and the CSM Monaco.