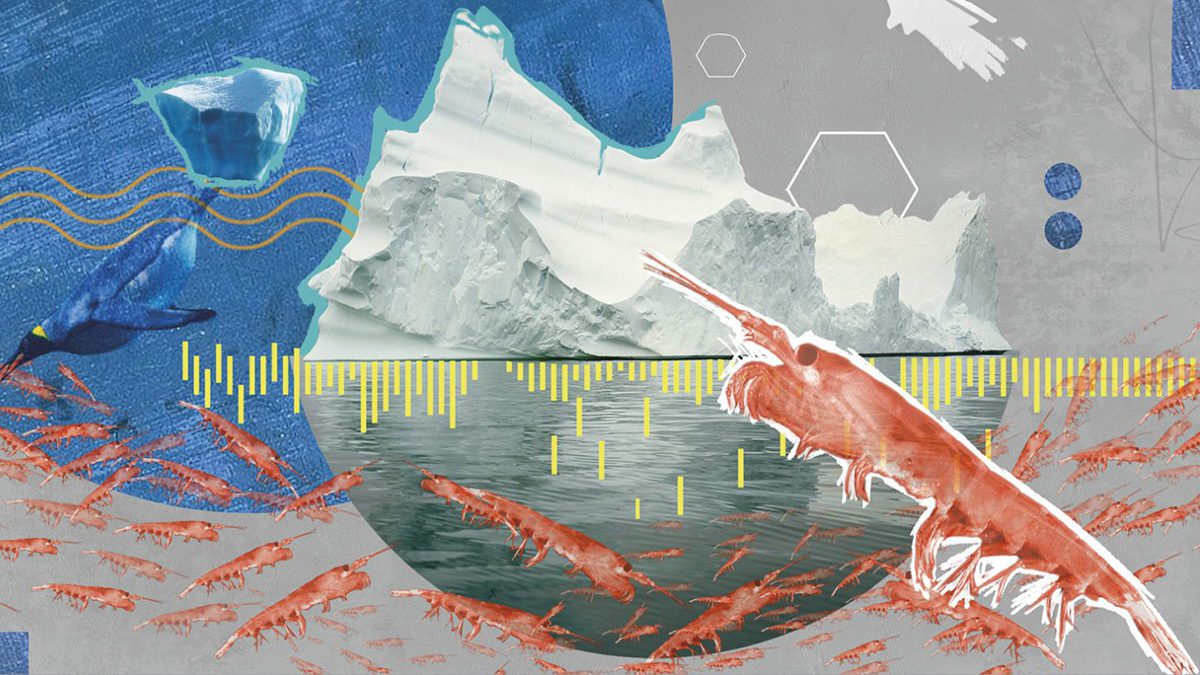

Life in the Antarctic requires capabilities that sound nearly mythical—powers of flight, swimming endurance, and fecundity—in an environment that is remote, cold, and windy. Here we present three animals that thrive there: albatrosses, Weddell seals, and emperor penguins. The WHOI scientists who study these top predators view them in the context of the entire marine ecosystem of the Southern Ocean, one that is undergoing rapid changes that will determine whether this wildlife thrives or passes into memory.

Albatrosses of the Southern Ocean (Diomedeidae)

By Hannah Piecuch

Long in flight, wingspan, and love, albatrosses of many species haunt the open water of the Southern Ocean. In a year, one bird might circle Antarctica two or three times, hunting in the stormiest seas on the planet.

Most human encounters with albatrosses take place on ships or fishing boats, as the birds ride the wind nearby foraging for squid. Above the open sea, an albatross can look slight, its lean wings outstretched as it cycles up and then drops to skim the surface of the water. Yet these birds have the widest wingspan on Earth. While size varies by species, wandering albatrosses’ wings stretch to over three meters (more than 11 feet).

When WHOI postdoctoral fellow and seabird scientist Francesco Ventura first saw albatrosses in flight in the Falkland Islands, what they were doing seemed impossible. “They can soar against the wind, faster than the wind, without flapping their wings,” he said.

The albatross uses the energy of the wind for a flight pattern called dynamic soaring. They start by flying into the wind to gain altitude, then they turn and descend downwind, using wind and gravity to gain speed. Then they hover along the surface of the water where there is less wind and less resistance. “There is a gradient, a band of different speed winds, and they gain aerodynamic kinetic energy from the wind by crossing that band,” Ventura said. “They are surfing.”

“Young albatrosses spend six years at sea, rarely touching land.”

When Ventura was working on his doctorate at the University of Lisbon, his advisor attached a global positioning tracker to a grey-headed albatross from South Georgia Island just before it flew into a storm. The bird had a cruising speed of 110 kilometers (about 68 miles) per hour for nine hours. What’s more, it didn’t just soar through the storm, it hunted, found food, and increased its bodyweight.

Even if they travel at great speeds, there is no rushing an albatross. This is a bird that takes its time: to learn flight, find a partner, and raise chicks. Young albatrosses spend six years at sea, rarely touching land. When they come back to the colony, courtship can take several years. Even after choosing a partner, they often don’t have a first chick until they are nearly a decade old. Once paired off, albatrosses are famously monogamous.

“Albatrosses live very individual lives,” said recent MIT-WHOI doctoral graduate Ruijiao Sun, who studied the population dynamics of a wandering albatross colony as a student in WHOI scientist Stephanie Jenouvrier’s Lab. “They only come back to the colony to bond with their partner, breed, and raise a chick. After a chick is raised, they take a sabbatical year and go back to sea.”

With such powers of flight and patience, what could possibly stress an albatross? Like many other creatures that live in the Antarctic region, these birds are impacted by human activity and climate change.

Fishing boat bycatch is a frequent cause of mortality. Some colonies are struggling because rats and mice have been introduced into nesting areas by humans and attack the chicks while the parents are out hunting. The rodents also bring new diseases. Both issues can lead to breeding collapse. Climate impacts are more complex to trace. In recent years, wind patterns in the Southern Ocean have concentrated towards the poles and wandering albatrosses have been observed taking faster, more efficient, foraging flights. Their colonies have experienced increased breeding success. At the same time, scientists anticipate that warmer sea temperatures are going to drive Antarctic fisheries into select regions, which could possibly increase the chances of seabirds getting entangled in fishing gear.

Population data is a powerful tool for conservation. These numbers can determine birds’ protections and endangered status. Sun—who entered this field because of her passion for conservation work—has seen this kind of research pay off. The wandering albatross colony she studies on Crozet Island had 500 breeding pairs when scientists first started observing it in the 1960s. By the 1990s, the number plummeted to 100. This was largely due to bycatch fatalities of female birds because they tended to hunt in the same area as tuna fisheries.

With guidance from scientists, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources and the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission required the fishing industry to change its practices. They now fish at night when albatrosses don’t hunt and have changed the hooks they use to minimize the chance of snaring one. As a result, the colony has begun to rebound, with about 300 breeding pairs annually.

The data that WHOI scientists like Jenouvrier, Sun, and Ventura gather about isolated albatross colonies tell a bigger story than the lives of individual birds. These seabirds travel thousands of kilometers across the open ocean. Observing them shows what is happening in the whole supporting marine ecosystem of the Southern Ocean.

Weddell seals (Leptonychotes weddellii)

By Daniel Hentz

Of the more than 6,400 known species of mammals, only one can claim the title of “southernmost living mammal,” and that’s the Weddell seal. Their evolutionary secret? They have fantastic mothers.

During the winter, Antarctica is at its least hospitable. Temperatures can drop to -40°F (-40°C), storms rage, and hunting for food must take place under abject darkness and crushing ocean depths. To avoid giving birth in the polar night, mother Weddell seals will stretch their pregnancy to 10 months by pausing the implantation of their embryos (a process called embryonic diapause). This helps expecting seals sync up the end of their gestation with the start of the summer season, buying time for their pups to grow and learn how to swim while there is still sunlight before the start of the austral winter in June.

“Weddell seal breastmilk is so viscous with fat that it is said to have the consistency of Elmer’s glue.”

Once born, new pups must drink a slurry of breastmilk that is so viscous with fat (more than 60%) that it is said to have the consistency of Elmer’s glue. Nursing seals rely on this organic milkshake to plump themselves up with an insulating layer of blubber. What’s more, this milk supplies their bodies with massive stores of iron, an important mineral that forms the building blocks of proteins such as hemoglobin and myoglobin. These chemicals help red blood cells and muscle tissue carry oxygen, which the seals need to dive for deep-sea prey like squid, prawns, and the Antarctic toothfish.

“It’s like having a built-in scuba system,” said Michelle Shero, a WHOI biologist who has studied Weddell seals for the past 13 years. “It’s all these different physiological oddities that make them a really cool study species.”

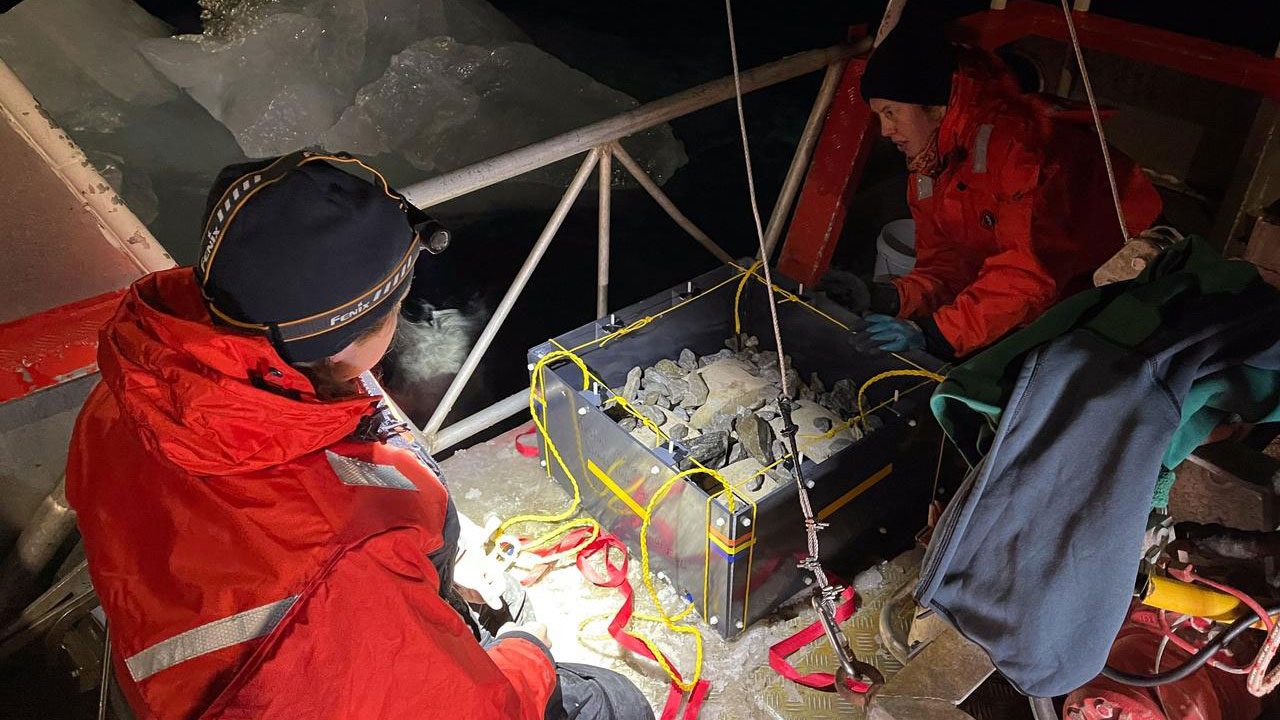

With no natural predators, Weddell seals have evolved to be far more approachable than other seal species. Thanks to this, Shero and her colleagues can gather data with relative ease, taking blood samples and performing routine health checks on what have become some of the world’s longest-studied mammal populations. Radio tags have allowed scientists to go a step further, tracking seals throughout the Antarctic winter. Over time, they’ve learned the animal is a diving machine.

The deepest recorded Weddell seal dives have topped 3,000 feet (nearly 1,000 meters), the height of a skyscraper while the longest foraging dive was recorded at 96 minutes. By comparison, the Guinness World Record for longest breath held by a free diver from Croatia was 24 minutes and 37 seconds (eat your heart out, Budimir Šobat).

“Imagine that whenever you got hungry, you had to chase your prey up and down the Empire State Building, all while holding your breath,” adds Shero. “That’s what these animals are often doing.” Getting to such depths, however, takes practice.

“The deepest recorded Weddell seal dives have topped 3,000 feet (nearly 1,000 meters) deep.”

Swimming lessons begin when pups are as young as three weeks. Mothers gnaw small portholes in the fast ice where young seals can practice diving. From these Antarctic kiddy pools, they beckon and coax their sated offspring with relentless whistles, until the pup reluctantly submits.

But none of this is a free lunch. While pups gorge and learn how to outswim Olympic divers, Weddell mothers are sacrificing tremendous amounts of energy in the form of fat stores.

“Mothers have really dramatic changes in weight throughout the year,” says Shero. “When a seal nurses its pup it can lose 30%-40% of its body mass and that’s totally [normal] for a Weddell seal.”

Today, climate change is making this already challenging motherhood nearly impossible. Rapidly warming temperatures have caused Antarctica to shed massive icebergs each year. In some areas, these bergs—some hundreds of meters tall and tens of miles wide—have blocked off important routes that seals need in order to reach nutrient-rich waters, where prey can be found. Other areas, however, could see a retreat in fast ice that has historically shielded Weddells against hungry killer whales.

Emperor penguins (Aptenodytes forsteri)

By Elise Hugus

We might chuckle at the sight of emperor penguins waddling over ice and belly-flopping into iceberg-studded waters, but these flightless birds would put Olympic swimmers to shame. In pursuit of fish, krill, and squid, they swim 250 kilometers to 500 kilometers (150 miles to 300 miles) in a single season and hold their breath for up to 20 minutes while diving. Thanks to their solid bones and a super-efficient circulatory system, they’re able to withstand the crushing pressures at ocean depths over 500 meters (1,640 feet). While diving, emperor penguins conserve oxygen by slowing their heart rates as slow as 15 beats per minute. Lesser creatures (like humans) that attempt such exertion in ice-cold water without an oxygen supply–and with a pulse this low–would soon pass out. Not these royal seabirds!

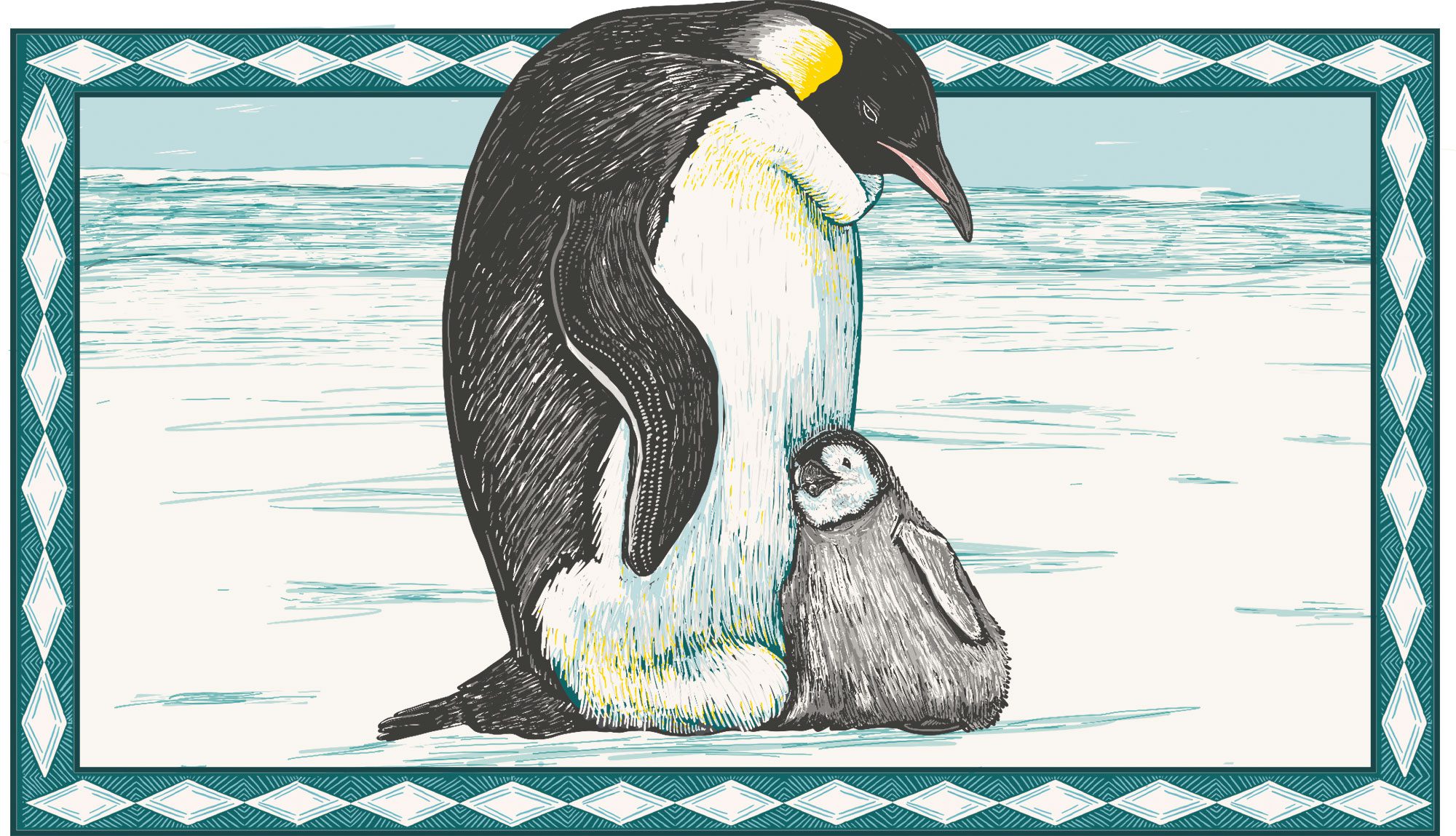

Emperor penguins are some of the most caring animal parents out there, but breeding comes at a cost. At the start of the Antarctic winter in March, they return from the sea and walk up to 100 kilometers (62 miles) over the sea ice to the colony of their own birth. After laying a single egg, the mother bird goes back out to eat (for the first time in months) while dad keeps that egg warm and rotated, surviving on only his own fat stores. After the egg hatches, the dads are usually still solo, so they feed their newborn chick a nutritious secretion called crop milk. Once mom returns, the parents take turns going out to forage and making sure the chick is warm and fed.

Dense, downy feathers and thick layers of fat provide insulation from the treacherously cold Antarctic winter, but that’s not enough to survive the continent’s -40°C to -70°C (-40°F to -94°F) average temperatures and hurricane-force winds. Huddled into groups, emperor penguins have developed an ingenious method of group survival, in which the birds on the outer part of the circle slowly rotate into the warmer core, spreading heat throughout the entire group. This is just one example of how penguins have adapted to the harshest weather on the planet—which they not only endure, but actually depend on, for survival.

“If we lose penguins, we’re not just losing them. It means that something bad is happening that can affect the whole system.”

—WHOI postdoctoral scholar Francesco Ventura

“I think the thing that sets penguins apart from pretty much everybody else is that they need the extremely challenging Antarctic winter conditions to breed successfully,” said Francesco Ventura, a WHOI postdoctoral scholar in WHOI biologist Stephanie Jenouvrier’s lab. “I cannot get my head around the fact that a male sits incubating an egg for two months while waiting for the female to come back, losing half of its body mass, but not starving.”

Emperor penguins do all they can to protect their young, but climate change is threatening the sea ice that they need to breed, raise their chicks, and molt their feathers. In the last 30 years, some parts of Antarctica have melted by more than 60%. According to a study co-authored by Jenouvrier, if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise at their current rates, 98% of the emperor penguin population could be wiped out by 2100. Last year, emperor penguins were listed as “threatened” under the U.S. Endangered Species Act—but Jenouvrier and other scientists say further protections are needed to ensure the species’ survival.

As a sentinel species, emperor penguins are Antarctica’s canary in the coal mine. Making use of over 50 years of data collected from tagged birds on a colony on Pointe Géologie Archipelago by scientists from the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS–the French National Centre for Scientific Research), Ventura and Jenouvrier are studying how changes in ice cover, sea surface temperature, and wind impact the birds’ foraging and breeding behavior. These observations allow them to predict outcomes for the colony under various climate change scenarios.

“Penguins are top predators, and so they are kind of a proxy for the whole ecosystem,” Ventura says. “If we lose penguins, we’re not just losing them. It means that something bad is happening that can affect the whole system.”