Can seismic data mules protect us from the next big one?

Researchers look to new seafloor earthquake detection systems for better detection and warning of seismic risk

This article printed in Oceanus Fall 2021

This article printed in Oceanus Fall 2021

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

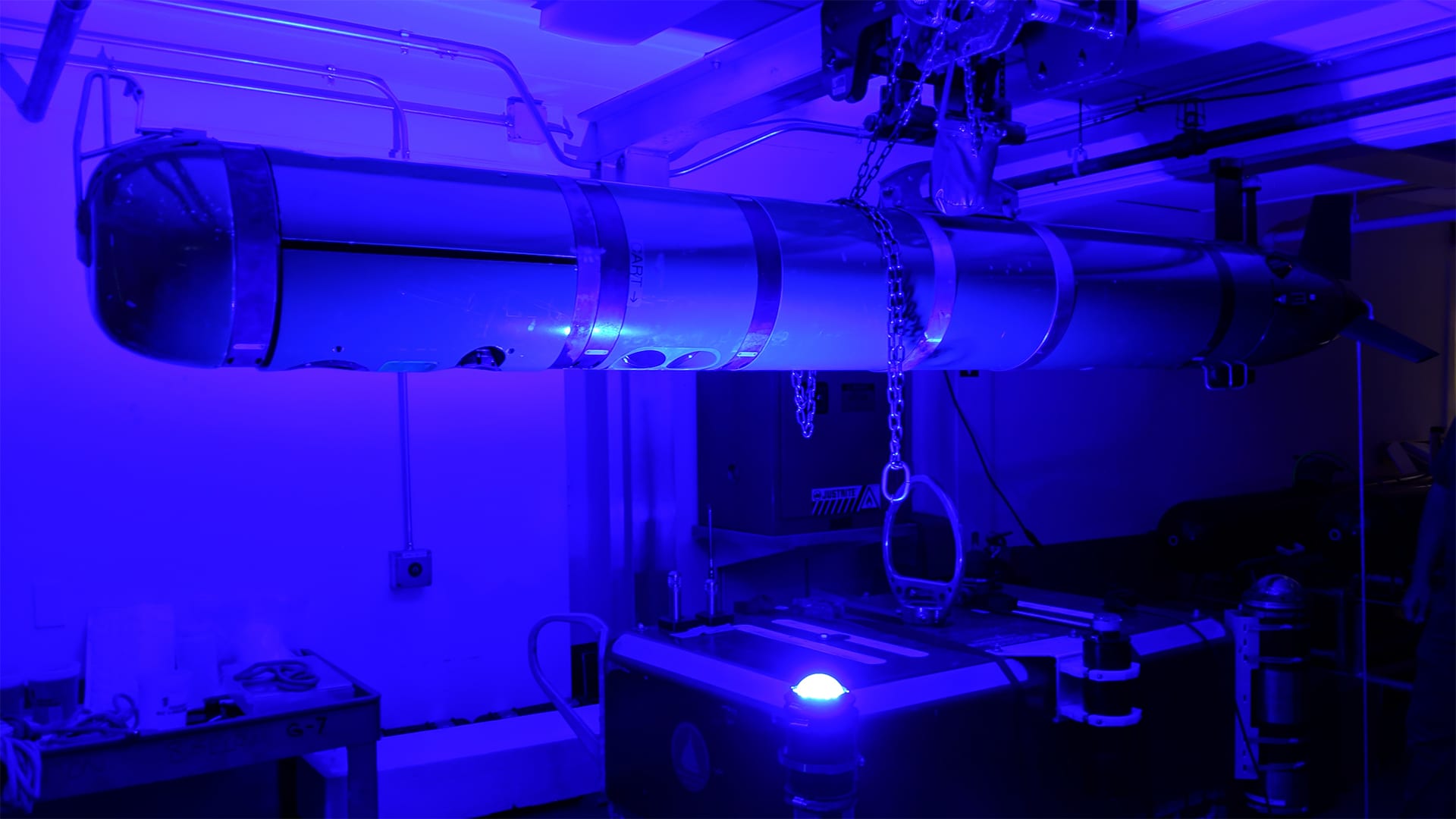

A REMUS-600 autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) communicates with an ocean-bottom seismograph (OBS) via a WHOI-developed optical modem link during lab testing. This link enables REMUS vehicles to act as "seismic data mules" whereby they offload data OBS stations without the need for ships or human intervention. (Photo by Dara Tebo, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

It was the day after Christmas, 2004, when all hell broke loose below the Indian Ocean.

Two of the Earth's tectonic plates that had been locked together for over a hundred years suddenly became unstuck. Moments later, a 9.1-magnitude earthquake juddered with the energy of dozens of Hiroshima-type atomic bombs, along with a massive tsunami that inundated parts of Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. In all, nearly a quarter-million lives were lost.

Ten thousand miles away in New England, things were calm. WHOI seismologist John Collins woke up to a quiet house in Concord, Mass., where he was visiting family during the Christmas holiday. Collins gathered his things and headed back to Cape Cod, where incidentally, he had to get a shipment of seafloor earthquake detection systems-known as Ocean Bottom Seismographs (OBS)-out the door.

"I was on Route 128 heading south towards the Cape," he recalls. "All of the sudden, news about the Sumatra earthquake came on the radio. The earthquake turned out to be so large, the seismographs we shipped out that day to put on the seafloor around the Hawaiian Islands picked up its aftershocks for many months afterwards."

Collins, along with WHOI researchers Jeff McGuire, Mike Purcell, Jonathan Ware, Norm Farr, Gwyneth Packard, and Jeff O'Brien are working to put OBS stations on the seafloor along a number of subduction zones-areas where tectonic plates meet-throughout the global ocean. "Subduction zones, such as those in Sumatra, Chile, Japan, Alaska, and the Pacific Northwest have the world's most destructive earthquakes and tsunamis that kill the most people," says Collins. "So, we need a dense array of OBS stations to monitor seismic activity in these areas."

The instruments use vibration sensors to measure ground motion, and underwater microphones known as hydrophones to measure sound. They're a critical tool for recording earthquakes and other seismic signals in the ocean, where most natural earthquakes occur. But access to crucial OBS data is pricey due to the exorbitant costs of deploying and recovering the instruments via ship. According to Packard, a senior engineer at WHOI, this has meant having to settle for "a scarcity of data."

"Data from the seismographs should get home fairly urgently given its importance in protecting coastal communities, but they're often deployed in areas of the ocean that are difficult to get to," she says. "If you're going ship-based, you can only get to these sites every so often."

Fortunately, that's changing. The researchers have recently added new autonomous capabilities to the REMUS autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) platform that enable the vehicles to offload data from ocean-bottom seismographs without the need for ships or human intervention. The torpedo-shaped subs use a combination GPS and inertial navigation to cruise beneath the ocean surface to the OBS, acoustics as it circles around the station, and optical communications to offload Gigabytes of data.

A village near the coast of Sumatra lays in ruin after the 2004 earthquake and tsunami that struck South East Asia. (U.S. Navy photo by Photographer's Mate 2nd Class Philip A. McDaniel (RELEASED)

"We built behavior into the vehicle that helps ensure successful data transfer depending on the strength of the optical signal," Packard explains. "REMUS can autonomously slow down or speed up as it circles above the OBS depending on signal strength."

Collins feels this "seismic data mule" paradigm is major breakthrough, and wouldn't be possible without the optical modem technology developed by WHOI research engineers Farr, Ware, and their teams. "Right now, WHOI is the only institution that has this optical modem capability-it's a huge edge for us," he says.

Once REMUS has retrieved the data, it surfaces to transmit mission-critical information to shore via a satellite link and then swims home.

The vehicle performs another important function when it visits an OBS: it provides the correct time. In seismology, earthquakes are located by calculating the time difference between a rupture and when earthquake waves reach OBS stations. If a seismograph's internal clock is off-even by a few milliseconds-it can be difficult to locate an earthquake with precision or detect tectonic changes that can hint at near-term ruptures.

"Clocks are super-important in our business," says Collins. "Since REMUS connects to GPS time every time it surfaces, it can bring the right time down to the seismographs to an accuracy of a few microseconds. This greatly increases the usefulness of the seismic data."

The researchers have successfully demonstrated the seismic data mule concept during recent test missions offshore of Cape Cod, and are working towards a longer-term vision they call "persistent autonomous presence"-where multiple REMUS vehicles, with long-range mission capabilities, are continuously monitoring OBS stations and sending the data home. This would provide fuller volumes of data that the broader scientific community can use to identify pre-cursory seismic activity more quickly.

"It's not just technology for technology sake-there's a real science driver here," says Collins. "We want to keep the instruments down there for multiple years without recovery so we can have better knowledge about the internal structure of earthquake faults and, ultimately, more advanced warnings for seismic risk."