Coral is a useful tool for scientists who want to understand changes in past climate, but recalling that history presents its own set of challenges.

In order to know anything about past climate from corals, we need to know their age. Ordinarily, scientists determine an object’s age by measuring the radioactive decay of some element in it. This decay occurs when an unstable form of the element, known as an isotope, changes into a stable one by ejecting a part of its nucleus.

Carbon is a useful element for dating objects because it’s so prevalent in our environment. The unstable isotope of carbon is 14C; its stable, unchanging isotope is 12C, where the numbers refer to different atomic weights. As 14C decays, the ratio of 14C to 12C in a sample changes over time. This change allows us to measure age.

We measure the rate of radioactive decay with what’s called a half-life. 14C’s half life is 5,730 years. This means that every 5,730 years, there’s half as much 14C as there was in the previous 5,730-year period. To extend this concept, in 11,460 years, there’s one-fourth the amount of 14C as there was originally.

Ordinarily, we measure the age of an object by comparing the current 14C/12C ratio with ratio of the past atmosphere, since that is where radioactive carbon comes from. The difference between the two is the age since it was formed. But with deep-sea corals, that difference is both the age since the coral was formed and the age of the water in which it grew.

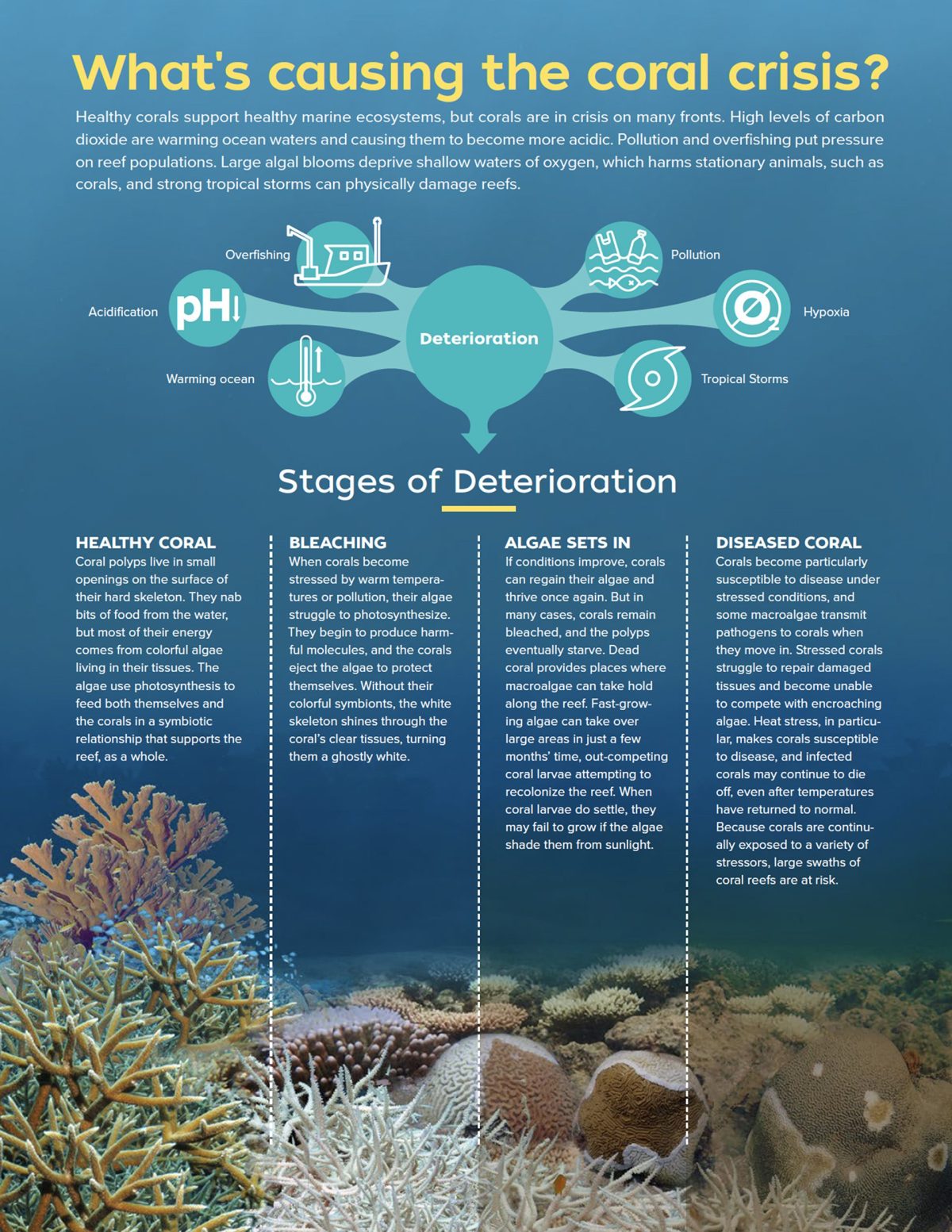

Since we want to know both of these values, we face the classic problem of having one measurement and two unknowns. In such cases, we need to somehow determine one of those unknowns from another angle. In the case of the deep-sea corals, we get their age by analyzing another element they contain: uranium.

Like carbon, uranium is radioactive. As it decays, however, it changes into another element, thorium. Fortunately, while a coral is growing it incorporates a lot of uranium, but no thorium. This means that as it ages its thorium/uranium ratio increases at a known rate. So, measurements of the thorium/uranium ratio provide a measurement of the coral’s age.

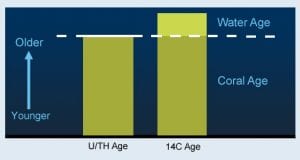

Now we know two things: time since the coral was formed (from uranium), and the sum of that time and the past water mass’s age (from carbon). So, the difference between these two gives us the radiocarbon age of the water.

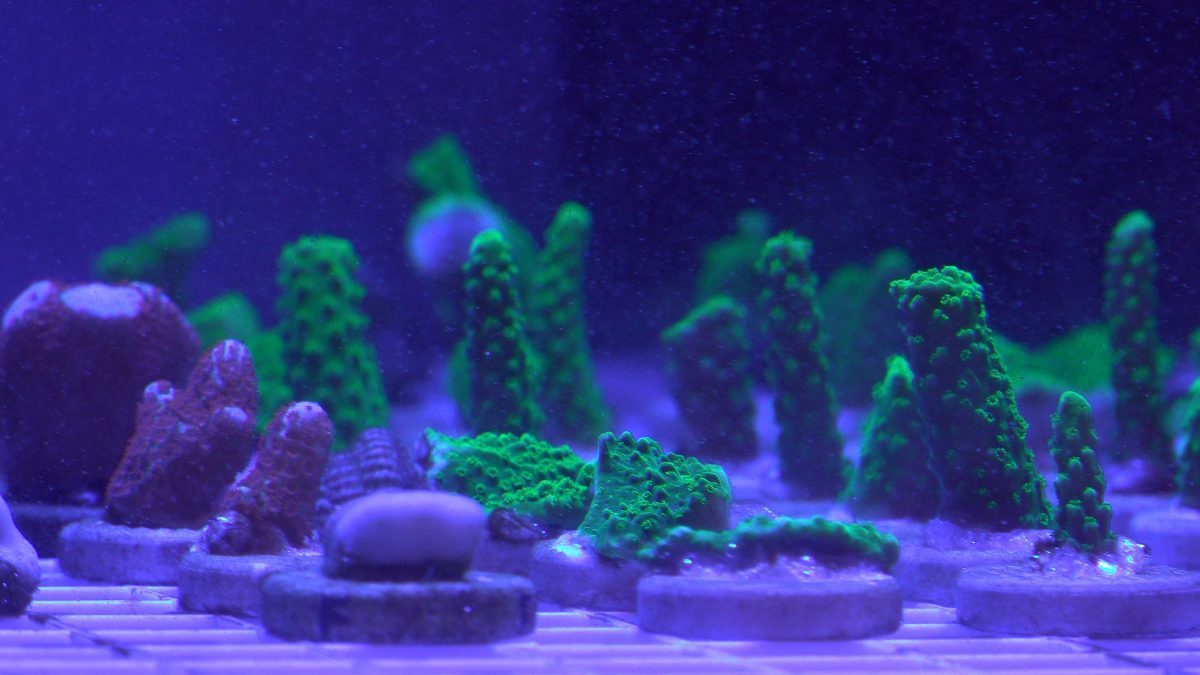

Collecting fossil corals at different depths is like collecting water profiles today. The coral records in its skeleton all that we need to know. We just have to find the ways to tease the information out.

A slice through the center of a long-dead brain coral is a slice through human and ocean history. This 1,000-pound coral grew near Bermuda for 200 years during the Little Ice Age. Radiating marks visible in the photo are grooves from the quarry saw that sliced through the coral. The coral changed its growth direction once in about 1650, and marine life eroded its surface, but scientists can analyze the coral's inner skeleton and decipher ocean temperatures during its lifespan. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The uranium-thorium “age” of a coral provides the chronological age of the coral. The radiocarbon (14C) “age” of the coral is the age of the coral, plus the age of the water in which it grew. Subtracting the former from the latter gives the age of the water in which it grew. Scientists use this information to learn about the rates at which water circulates through the oceans. (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

See Also

OCEANUS MAGAZINE—Growing a little each day, coral skeletons keep a daily archive of past ocean temperatures

What Other Tales Can Coral Skeletons Tell?

OCEANUS MAGAZINE—Scientists strive to get into the genes of fossil corals to extract their history