Ocean Life

5 unlikely ocean friendships

The ocean may seem like a “fish eat fish” world. But look more closely and you’ll discover some unlikely allies. Check out these surprising examples of symbiotic relationships between species that keep each other safe, fed, and healthy.

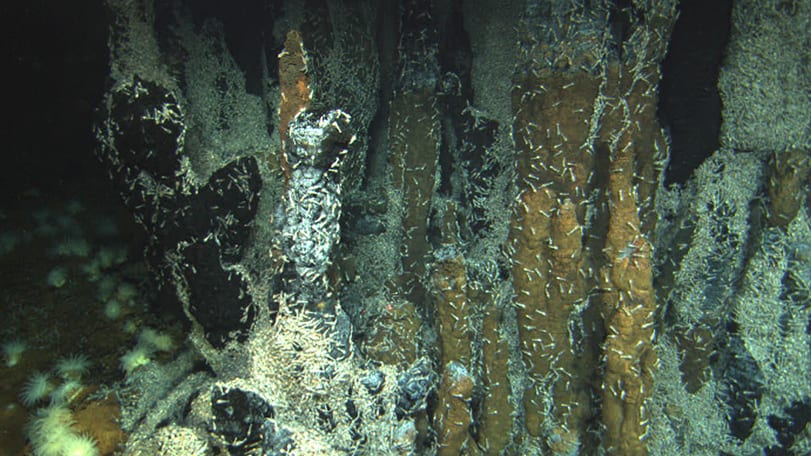

Giant Tube Worms and Bacteria

In 1977, scientists discovered hydrothermal vents. These seafloor hot springs release mineral-rich water that attracts an abundance of life, including shrimp, crabs, and six-foot-tall tubeworms. But with no sunlight to fuel the food web, what are these animals eating? Deep-sea tubeworms (Riftia pachyptila), it turns out, have no mouth, digestive tract, or anus—they survive with help from bacteria inside their bodies. The tubeworms’ feather-like red plumes act as gills, absorbing oxygen from seawater and hydrogen sulfide from the vent fluids, which the bacteria oxidize to create energy. In the process, they transform carbon dioxide into organic carbon—food for the tubeworms, which can grow an amazing 30+ inches per year.

Gobies and Shrimp

Small fish called gobies and certain species of pistol shrimp are nearly inseparable. As youngsters, they form a relationship that lasts until adulthood, foraging for food and living together in burrows in the seafloor. The pistol shrimp has poor vision, making it vulnerable to predators when out foraging. The goby, which has excellent eyesight, keeps watch over the shrimp and alerts it to any impending danger. In exchange, the shrimp excavates their shared burrow, allowing the goby to move in and even mate there.

Pom-Pom Crab and Anemone

The saltwater pom-pom, or boxer crab (Lybia edmondsoni), is an inch-long crustacean with a flimsy external shell. While it may look like easy prey, this cunning little crab carries a powerful weapon: venomous anemones with tentacles armed with stinging cells. By waving the anemones in their claws like boxing gloves—or scary pom-poms—the crabs can warn off or sting predators to protect themselves (or, just use the anemones’ tentacles to collect food particles off the seafloor). But the relationship may only go one way—scientists have not yet discovered what, if anything, the anemones get out of it.

Manta Rays and Remoras

Manta rays can weigh as much as 5,000 pounds, gliding through the ocean with massive wingspans of up to 25 feet. At no more than two pounds and only three-feet long, remoras are much smaller—but they come with some big benefits. These little fish use their suction-cup-like dorsal fins to attach themselves to the broad, cartilaginous underside of a manta, clearing off bacteria and parasites without damaging the ray’s skin. In return, these hitchhikers gain protection, a free ride, and a free lunch. Manta rays are sloppy eaters, filter feeding on tiny crustaceans and other plankton that float through the water, giving the remoras ample opportunity to scavenge the scraps.

Eel and Wrasse

The bluestreak cleaner wrasse is the fishy “dentist” of coral reefs. To receive a wrasse’s services, larger fish such as moray eels visit cleaning stations along the reef, opening their large mouths wide. The wrasse swims inside, gently feeding on excess slime, dead skin, scales, and parasites. Wrasses often work in pairs, and several large fish may wait in the vicinity for their turn at a cleaning. In exchange, the wrasses don’t get eaten—and gain protection from potential enemies. But if a wrasse gets hungry and takes a bite from a “patient’s” flesh, it may lose a loyal customer!