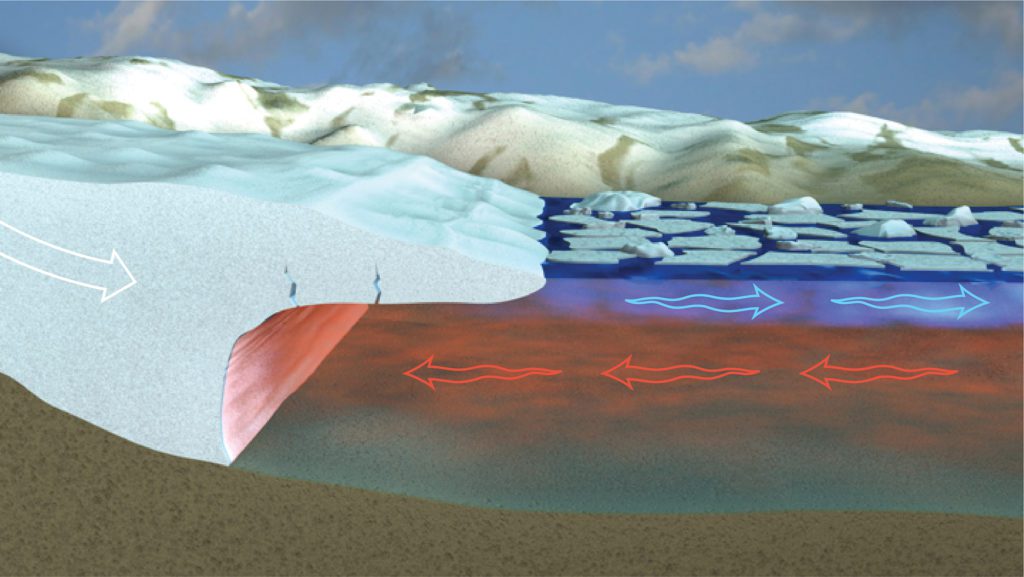

In recent years, the deep waters coming in from the ocean have been much warmer than in the past — up to 6°C (nearly 43°F). The additional heat weakens the ice tongue and promotes cracking and calving from the glacier front.

Terrence Joyce (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

This week’s unexpected heat wave across much of the Northeast and Midwest, couple with recent reports about the surprisingly fast collapse of an Antarctic ice shelf the size of Rhode Island, has heightened fears of long-term rise in temperatures brought about by global warming. But this fear may be misguided. In fact, paradoxically, global warming could actually bring colder temperatures to some highly populated areas like Eastern North America and Western Europe.

Here’s what might happen: In the North Atlantic, a 10-foot layer of fresh water - some of which may be coming from melting ice in the Arctic - has been accumulating and lowering the salinity of the ocean to depths of more than a mile for the past 30 years. Fresh water in the ocean may not sound cataclysmic, but it can upset the ocean currents that are the key to our planet’s climate control system.

In February, oceanographers presented new evidence that this northern freshwater buildup could alter currents in a way that would cause an abrupt drop in average winter temperatures of about 5 degrees Fahrenheit over much of the United States and 10 degrees in the Northeast. That may not sound like much, but recall the coldest winters in the Northeast, like those of 1936 and 1978, and then imagine recurring winters that are even colder, and you’ll have an idea of what this would be like. This change could happen within a decade and persist for hundreds of years.

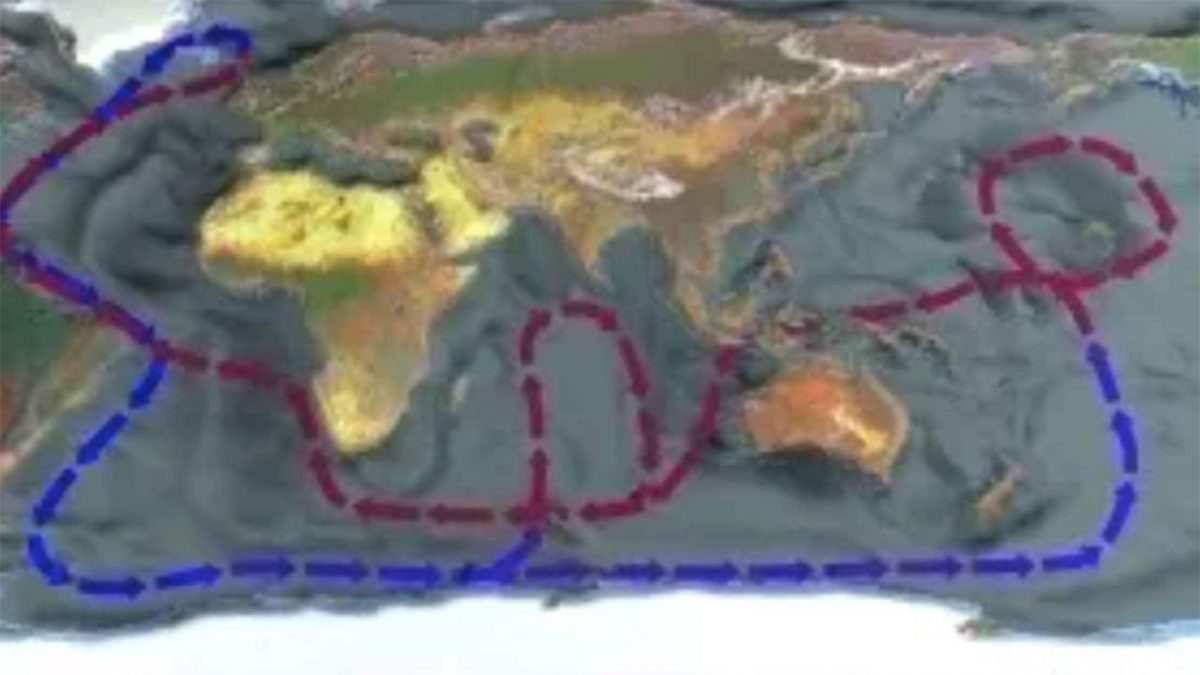

Under normal circumstances, the famous warm waters of the Gulf Stream, carrying heat absorbed in the tropics, move up the East Coast of the United States and southeastern Canada and then angle toward Europe, warming the overlying atmosphere and surrounding land as they go. As the Gulf Stream system carries warm, salty water north, the atmosphere cools it, making it dense enough to sink to great depths. The plunge of that great volume of water helps propel a global system of currents sometimes called the great ocean conveyor. But add too much fresh water, and North Atlantic waters become less salty and less dense. They stop sinking. The Gulf Stream slows or is redirected southward. Winters in the North Atlantic region get significantly colder.

Changes in the conveyor were responsible for some of the most noticeable climate changes in scientific history. About 12,000 years ago, as the earth emerged from the most recent Ice Age and the North Atlantic region warmed, an influx of fresh water - perhaps from melting ice sheets - shut down the great conveyor and plunged much of the Northern Hemisphere back into ice-age conditions that lasted 1,000 years. About 500 years ago a reduction of the ocean conveyors may have turned the climate in northern Europe and the northeastern United States much colder, during what became known as the Little Ice Age, which lasted for about 300 years. In America, the Little Ice Age coincided with the notorious winter at Valley Forge.

There is not enough evidence for scientists to know for sure whether the influx of fresh water in the North Atlantic has come from an already altered ocean circulation, changes in rainfall patterns or rivers, or glacial and Arctic Ocean ice. We don’t know the exact threshold at which sinking, and the great ocean conveyor, could stop. A global ocean-observing system would greatly enhance our ability to monitor changes that can spawn major, long-lasting climate shifts like these and lead to reliable predictions of what may follow. But the evidence we do have suggests that global warming could actually lead to a big chill.

Terrence Joyce is a senior scientist and chairman of the department of physical oceanography at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.