Henry Bryant Bigelow Medal in Oceanography

Award Description

The Bigelow Award is presented "to those who make significant inquiries into the phenomena of the sea." The award was established in 1960 by the Institution's Board of Trustees in honor of the first Director, biologist Henry Bryant Bigelow, who was also the first recipient. Bigelow served as WHOI Director from 1930 to 1940, as President of the Corporation from 1940 to 1950, and Chairman of the Board of Trustees from 1950 to 1960. The award, a medal and cash prize, is given to individuals in any field of oceanography without limitation as to age or nationality and is presented for an outstanding contribution to oceanography rather than a cumulative record of achievement. Nominations for the award were received from prominent scientists around the world.

About Henry Bryant Bigelow

Founding Director of WHOI (1930-1939)

Henry Bryant Bigelow was a pioneering oceanographer and marine biologist. He is credited with describing 110 new species for science and authoring some 100 scientific papers over the course of his career.

Bigelow’s love of the outdoors started early and barely wavered. He was raised in Boston, but spent his summers in and around the waters of Cape Cod, which inspired him to become an amateur naturalist as a young man. His knowledge of natural things grew as a student at Harvard University where, in his senior year, he had the opportunity to accompany Alexander Agassiz, director of the school’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, on an expedition to the Maldives in the Indian Ocean.

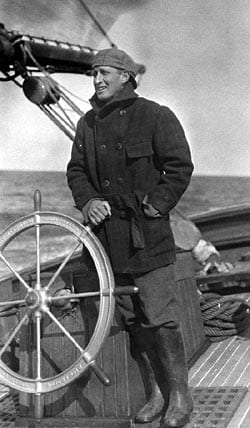

That trip sparked in Bigelow a passion for the ocean, which he continued to study alongside his mentor until Agassiz’s death in 1910. A conversation with Sir John Murray, the renowned Scottish oceanographer who delivered Agassiz's eulogy, formed the basis for yet another important phase in Bigelow’s career: his exploration of the Gulf of Maine. From 1912 to 1922, Bigelow conducted several extended studies aboard the U.S. Fisheries Service schooner Grampus, eventually assembling three book-length monographs on the fish, plankton, and physical oceanography of the Gulf.

Bigelow’s work piqued the interest of Frank Lillie, then president of the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., who proposed to the National Academy of Sciences they establish a committee to examine the state and future of oceanography in the U.S. In 1928, Bigelow prepared a report for the new committee, in which he outlined the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to marine science. “We believe that our ventures in oceanography will be most profitable if we regard the sea as dynamic, not as something static, and if we focus our attention on the cycle of life and energy as a whole in the sea, instead of confining our individual outlook to one or another restricted phase,” Bigelow wrote in his summary of the report.

This work ultimately led to the founding of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in January 1930. Lillie and Bigelow worked together to secure funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and in February of that year, the foundation committed $2 million for buildings and endowment, and continued to support its work for the next decade. Bigelow took the helm as the Institution's first director and set to work gathering a team of researchers who could fulfill his interdisciplinary vision. Among his recruits were Alfred Redfield, a professor of physiology at Harvard Medical School and one of Bigelow’s closest friends, and Columbus Iselin, a former student of Bigelow’s at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology who later succeeded him as director of WHOI in 1940. With Iselin, Bigelow also helped design the first purpose-built oceanographic research vessel in the U.S. and the first in a long line of ships operated by WHOI—the steel-hulled ketch Atlantis.

After stepping down as director of WHOI in 1939, Bigelow spent 10 years as President of the Board and another decade in the honorary role of Founder Chairman, all the while maintaining a professorship at Harvard. He retired in 1967 and passed away that same year at the age of 88, survived by his wife Elizabeth and two of his children. The July 1968 issue of Oceanus magazine was dedicated to Bigelow’s legacy, and contained testimonials by his friends and colleagues of his scientific achievements and his leadership. Many admired Bigelow for his sense of discovery, which helped motivate those who worked with him to explore the ocean in a new way. “Though his excitement was in the discovery of new facts, he was not one to be concerned primarily with learning more and more about less and less,” said Redfield. “He encouraged new fields of inquiry and broadened our conception of what marine science could be.”

Bigelow’s published work extends over 68 years and covers a wide range of fields, but he will always be remembered as one of the founders of modern oceanography, which colleague Michael Graham described as, "oceanography with an ecological aim [that seeks] an explanation of the interconnections based on a full knowledge and the applications of other branches of science.”

Henry Bryant Bigelow (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Henry Bigelow and WHOI Director Paul Fye admire the Henry Bryant Bigelow Medal in 1961. (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Henry Bigelow steers the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries vessel Grampus. While using the boat for surveys in the Gulf of Maine, Bigelow found it was not stable enough for oceanographic work, and its small hoisting engine could not handle heavy equipment. He applied his experience with Grampus to the design of WHOI's first research vessel, Atlantis. (Courtesy of WHOI Archives)