Underwater cameras tackle tough questions for fishery

Ocean scientists and fishermen team up to document seal-fishing net interactions

By Evan Lubofsky | September 4, 2019

One of the tough realities of commercial fishing is that fishermen and seals sometimes compete for the same fish. And when they do, interactions between the animals and fishing nets can occur, leaving fishermen with ruined catches and damaged fishing gear, and seals with the possibility of lethal entanglements.

To come up with new ways to prevent such interactions between marine animals and fisheries, ocean scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and the Center for Coastal Studies (CCS) are working with local fishermen on Cape Cod to understand exactly what happens when seals and other marine mammals invade a fishing net to forage.

“Fishermen are a great source of knowledge and a big part of the conservation equation here in New England, where the commercial fishery is so important,” said Alex Bocconcelli, a research specialist at WHOI. “But they are also facing hard issues related to both lost catch and lost fishing opportunities from depredation. So, we’re leveraging the strong relationships we have with the local commercial fishing industry to figure out what’s going on, and more importantly, what can be done to help reduce the economic and ecological impacts.”

Mitigating impacts

The costs of depredation—when marine animals prey on fish caught in nets—can be high on both fronts. On the economic side, it can reduce the amount of sell-able fish and lead to torn fishing nets. “A five-inch opening in the net can quickly become a 15-inch hole when a seal gets caught and tries to free itself,” said Doug Feeney, a commercial fisherman based in Chatham, Massachusetts. When fishermen spend time mending nets and sorting through their catch for fish they can sell, they often lose valuable fishing time, which compounds the financial hit.

From an ecological standpoint, the incidental by-catch of gray seals—which occurs even when they’re not preying on fish caught in the net—is a leading cause of mortality among these and other protected marine mammals.

“With the successful rebound of marine mammal populations in New England—seals in particular—fishery interactions and resulting frustrations build," said Andrea Bogomolni, a faculty member of Shoals Marine Laboratory who previously studied marine mammal and ocean health science at WHOI. "We’ve worked with our commercial fishing partners to ask questions and design experiments together, relying on each of our unique areas of expertise to address these interactions."

A sustainable collaboration

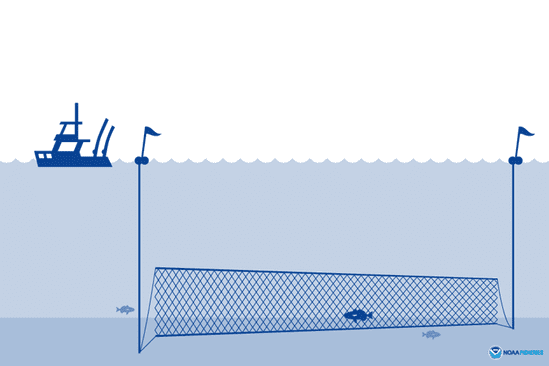

Bocconcelli and Bogomolni have been working with Feeney and scientists from CCS to document the behavior of seals and other animals in and around fishing nets just east of Cape Cod—an area that has seen steady growth in gray seal populations over the past few years. The team has mounted an array of five underwater cameras across the top or “headrope” of a gillnet—a ten-foot tall wall of mesh netting that extends as wide as the wingspan of a 747 jumbo jet—to get an unprecedented view of the encounters. They are also relying on the use of a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to periodically survey the nets. The ROV takes real-time video snapshots of activity below the surface to supplement the top-mounted cameras.

“This is the first time anyone has captured video of active sink-gillnet fishing in the northeast U.S. that we know of,” said Owen Nichols, director of Marine Fisheries Research for CCS. He says that assessing and documenting depredation by seals and other marine animals is often done by human observation on deck. “In general, we don’t know much about what goes on around the fishing gear until we see what comes over the rail,” he said. “That’s when we can see the bite marks and other catch damage in the net, as well as occasional damage to the fishing gear itself.”

Getting a clear view

The underwater imagery has the potential to facilitate a shared learning experience between the scientists and fishermen, but capturing clear footage isn’t without its challenges. The gillnet site is so rich with marine life, the cameras are often filming through a thick fog of fish biomass. Turbulence from surrounding ocean currents can distort the view even more by pushing suspended sediment and organic material around like confetti. Fortunately, the cameras are mounted on tightly-anchored nets, which helps to minimize the amount of camera movement and resulting visual noise.

Once the nets are pulled up, the team examines the catch for bite marks and other visible injuries that may have occurred. “Seals will often bite into the belly of the fish to eat the livers,” said Bocconcelli. Then, the researchers review the video footage for any depredation events, and can later correlate the imagery with stomach content analysis data if necessary to verify what a particular animal was feeding on. Gray seals aren’t always the culprits—spiny dogfish and harbor seals are among the other predators known to scavenge from fishing nets as well.

A level playing field

The study, which is funded through grants from the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation and the Marine Mammal Commission, was launched last summer and is expected to run through the end of 2019. Feeney says the collaboration so far has been strong, something he credits to mutual respect between him and the scientists. “We’re all on the same even playing field, and no one is pulling the ‘I’m a scientist’ or ‘I’m a fisherman’ card,” he said. “Commercial fishermen and seals need to coexist, so we’re all just working hard to come up with answers.”

The cameras have collected close to 100 hours of video footage, which is still being analyzed. The researchers feel that the camera array will be invaluable for documenting the behavior of seals engaged in depredation, and thus helping to inform commercial fishermen on measures they can take to prevent these costly interactions.

“If we see that most interactions happen at a certain time, it might help the fishermen tune their fishing to maximize their catch without having to worry as much about the presence of predators,” said Nichols. “Or maybe they can reconfigure their gear if they see a lot of interactions happening at the top or bottom of their nets. It puts the knowledge and decision-making ability in the fisherman’s hands.”

Bocconcelli agrees and says another measure that fishers could take is shortening their soak times—the amount of time nets are set on the seafloor—to give seals and other predators less time to get at the catch. This could also lower seal mortality rates associated with entanglements.

“If we can empower the commercial fishing community even a little, we can extend this out to other fisheries and encourage even more collaboration on this important local issue,” he said.