News Releases

Chief of Naval Operations Visits WHOI

Global ocean research projects and marine technology advances were among the topics presented on September 9 when the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Admiral John Richardson, paid a visit to WHOI.

Read MoreAncient Skeleton Discovered on Antikythera Shipwreck

An international research team discovered a human skeleton during its ongoing excavation of the famous Antikythera Shipwreck (circa 65 B.C.) this month. The shipwreck, which holds the remains of a Greek trading or cargo ship, is located off the Greek island of Antikythera in the Aegean Sea. The first skeleton recovered from the wreck site during the era of DNA analysis, this find could provide insight into the lives of people who lived 2100 years ago.

Read MoreFree-swimming Ocean Gliders Help Scientists Understand Storm Intensity

A regional team from WHOI, Rutgers University, the University of Maine, the University of Maryland, and the Gulf of Maine Research Institute mobilized Friday in advance of Hurricane (now Tropical Storm) Hermine’s arrival in the Northeast to gather data from new ocean instruments that will help better predict the intensity and evolution of future tropical storms along the US East Coast

Read MoreWHOI Receives $1 Million Award for Early-Career Scientists from Grayce B. Kerr Fund

The Grayce B. Kerr Fund has awarded the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) $1 million to establish an endowment in memory of WHOI Life Trustee Breene Kerr.

Read MoreThe Sound of a Healthy Reef

A new study from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) will help researchers understand the ways that marine animal larvae use sound as a cue to settle on coral reefs. The study, published on August 23rd in the online journal Scientific Reports, has determined that sounds created by adult fish and invertebrates may not travel far enough for larvae – which hatch in open ocean – to hear them, meaning that the larvae might rely on other means to home in on a reef system.

Read MoreMoore Foundation Supports WHOI Effort to Revolutionize Ocean Research

A $250,000 award from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation supports WHOI scientists and engineers to explore a new path for ocean research focused on rapid software and hardware innovation.

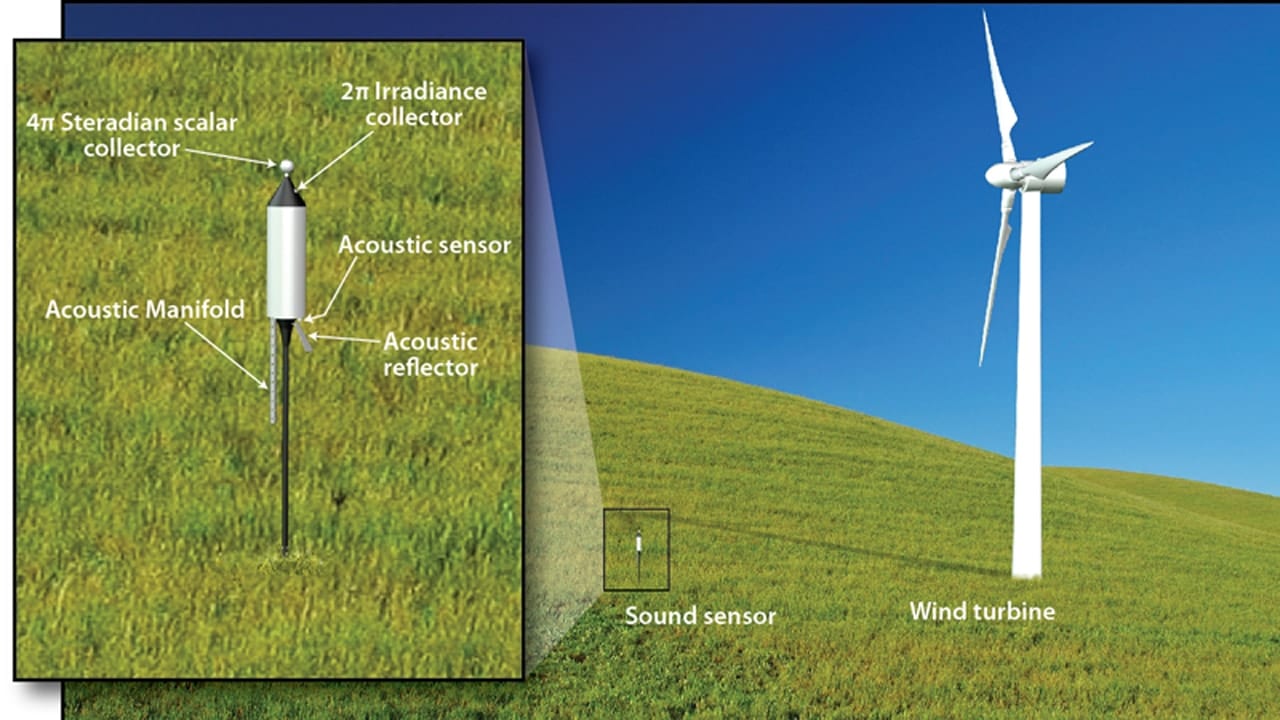

Read MoreWoods Hole Oceanographic Institution Announces Innovative Wind Turbine Monitor

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) announces the issuance of U.S. Patent No. 9,395,338 for self-regulating terrestrial turbine control through environmental sensing. Wind energy is a widespread clean alternative to energy…

Read MoreWHOI Announces 2016 Ocean Science Journalism Fellows

Seven writers, radio, and multimedia science journalists from the U.S., England, and India have been selected to participate in the competitive Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) Ocean Science Journalism Fellowship program. The program takes place September 25-30, 2016, in Woods Hole, Mass., on Cape Cod.

Read MoreWHOI is a ‘Rising Star’ in Research Performance

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) was named one of the top 25 institutions in North America in the Nature Index 2016 Rising Stars, which identifies the countries and institutions that have significantly increased their research studies published in high-quality research journals.

Read MoreScientists Now Listening for Whales in New York Waters With Real-time Acoustic Buoy

Scientists working for WCS’s (Wildlife Conservation Society) New York Aquarium and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) now have an “ear” for the New York region’s biggest “voices and singers”‘ the whales of New York Bight.

Read MoreSwansea University Professor Receives Prestigious Fulbright Award to Study at WHOI

David Lamb, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at Swansea University in Wales, will conduct research at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) as part of an All Disciplines Scholar Fulbright AwardâÃÂÃÂone of the most prestigious and selective scholarship programs operating worldwide.

Read MoreSharkCam Tracks Great Whites into the Deep

On the first trip to study great white sharks in the wild off Guadalupe Island in 2013, the REMUS SharkCam team returned with an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) tattooed with bite marks and some of the most dramatic footage ever seen on Discovery Channel’s Shark Week: large great white sharks attacking the underwater robot, revealing previously unknown details about strategies sharks use to hunt and interact with their prey.

Read MoreArtifacts Discovered on Return Expedition to Antikythera Shipwreck

An international research team led by archaeologists and technical experts from the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports and WHOI has discovered spectacular artifacts during its ongoing excavation of the famous ancient Antikythera Shipwreck off the Greek island of Antikythera in the Aegean Sea.

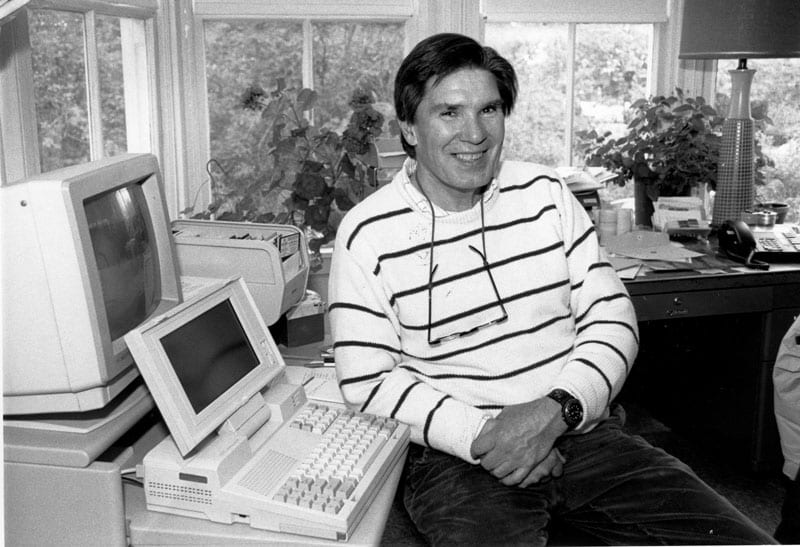

Read MoreHistoric Marine Mammal Sound Archive Now Available Online

Over his more than 40 years as a scientist at WHOI, William Watkins led the effort to collect and catalog the vocalizations made by marine mammals. Now, a team from WHOI has launched the online, open access William Watkins Marine Mammal Sound Database.

Read MoreMIT/WHOI Joint Oceanography Program Achieves Milestone of 1,000th Degree

One of the nation’s preeminent graduate programs in oceanography has achieved a major milestone: This year, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) Joint Program will confer its…

Read MoreFishermen, Scientists Collaborate to Collect Climate Data

To help understand the ongoing changes in their slice of the ocean, a group of commerical fishermen in southern New England are now part of a fleet gathering much-needed climate data for scientists through a partnership with the Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation (CFRF) and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

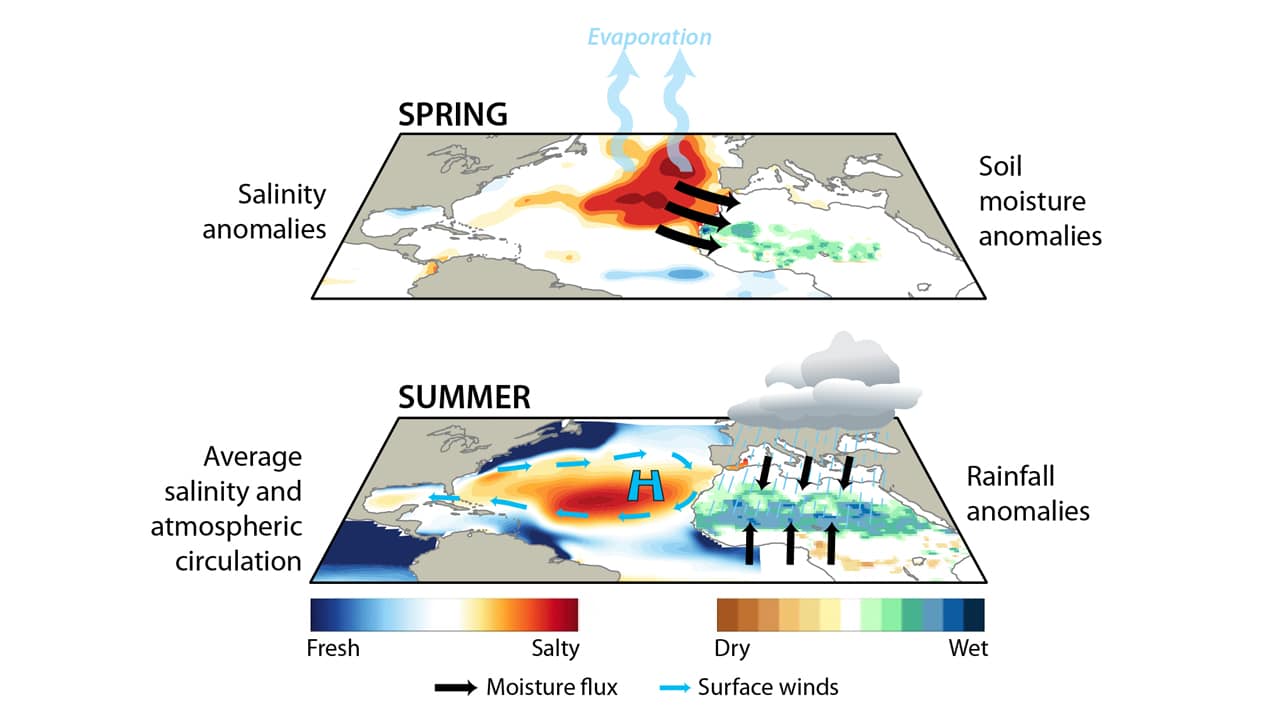

Read MoreStudy Offers Clues to Better Rainfall Predictions

WHOI scientists have found a potential path to better seasonal rainfall predictions. Their study shows a clear link between higher sea surface salinity levels in the North Atlantic Ocean and increased rainfall on land in the West African Sahel, the area between the Sahara Desert and the savannah in Sudan.

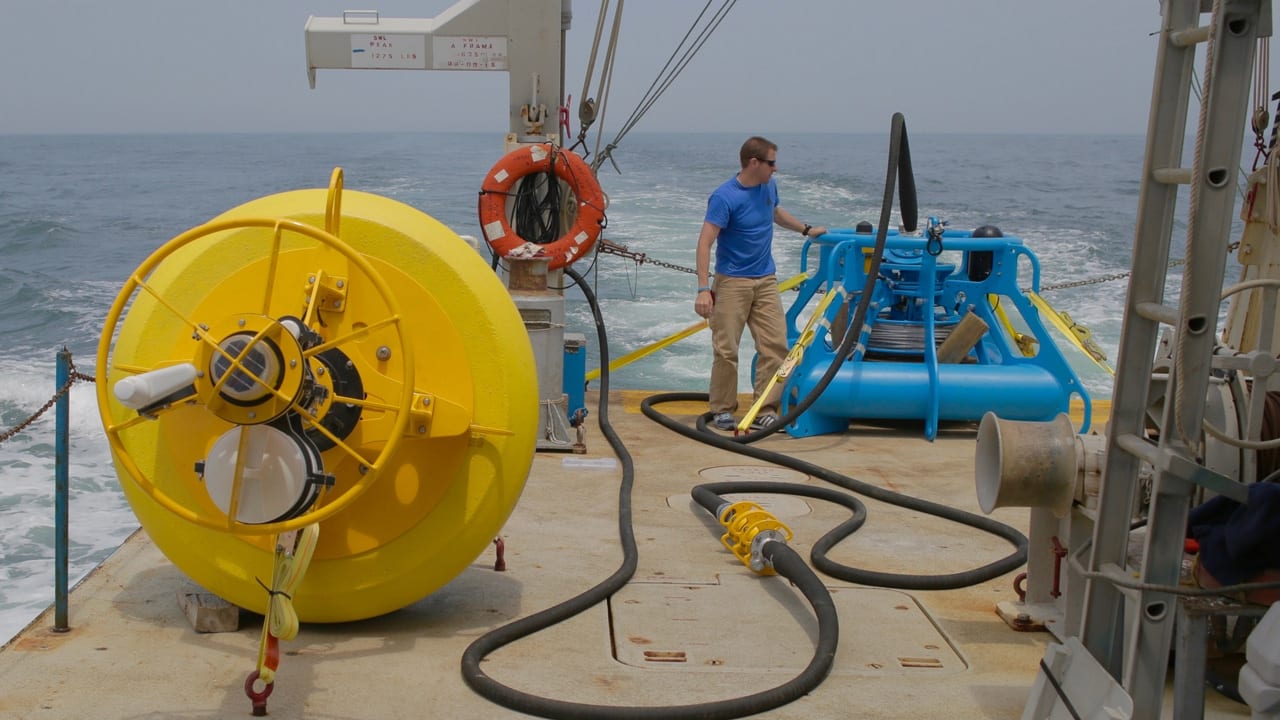

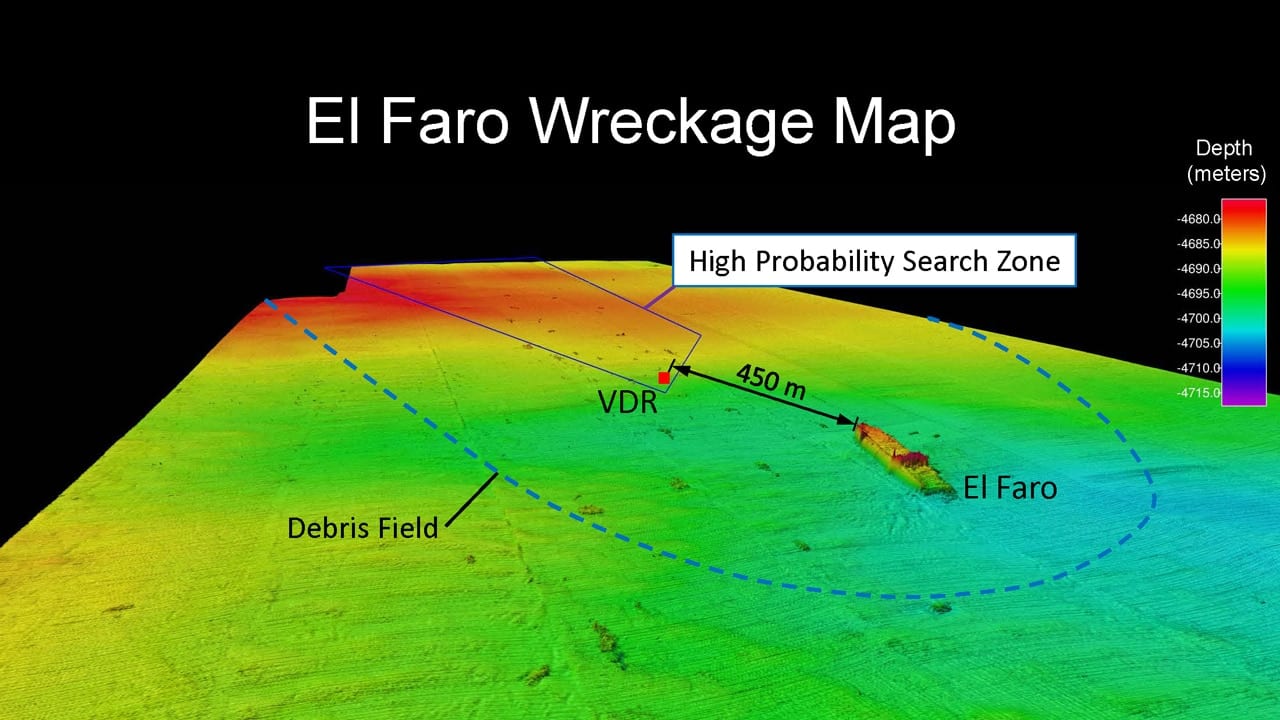

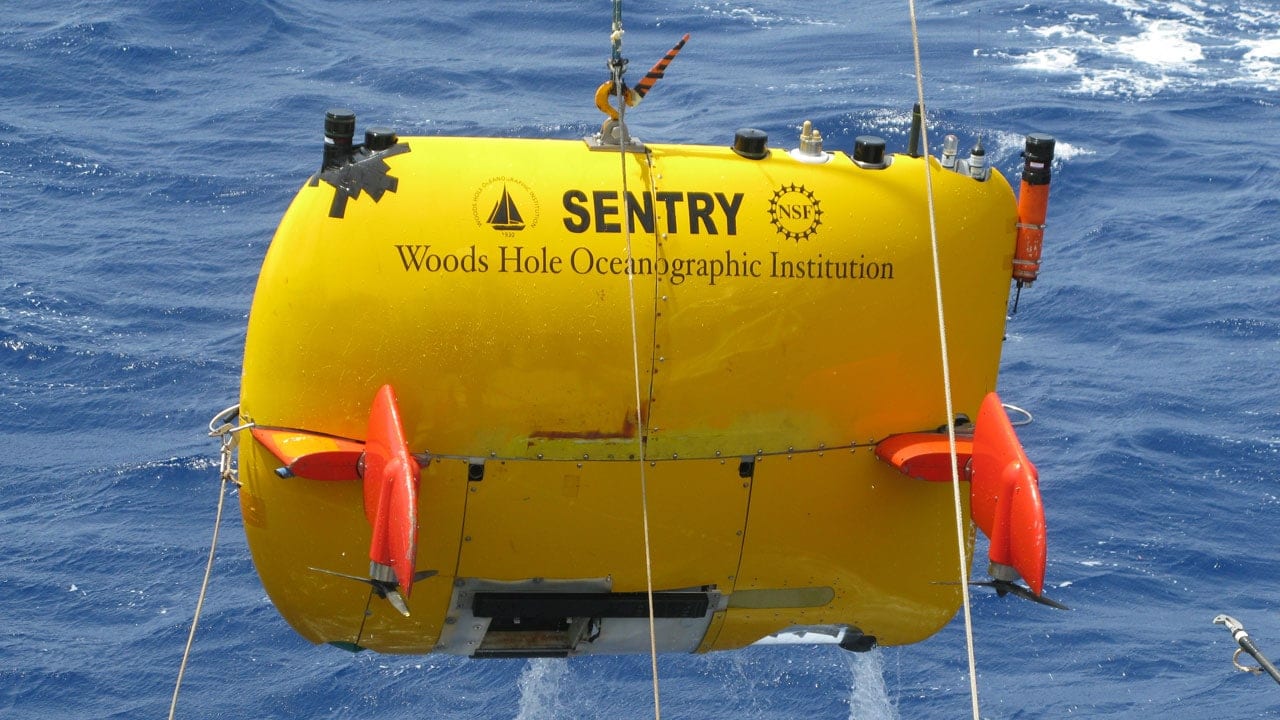

Read MoreWHOI Technology Used in Locating El Faro Data Recorder

Technology and vehicles developed and operated by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) scientists and engineers were instrumental in assisting the NTSB in locating the voyage data recorder (VDR) of El Faro.

Read MoreWHOI Assists in Locating El Faro Voyage Data Recorder

A team of scientists and engineers from the NTSB, Coast Guard and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) have located the voyage data recorder (VDR) of the sunken El Faro cargo ship.

Read MoreWHOI to Assist in NTSB Search for El Faro Data Recorder

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution will assist the National Transportation Safety Board as it undertakes its second search April 18, 2016, for the vessel data recorder (VDR) of the sunken El Faro cargo ship.

Read MoreSteve Elgar Named National Security Science and Engineering Faculty Fellow

Steve Elgar, a senior scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), has been selected as a 2016 National Security Science and Engineering Faculty Fellow (NSSEFF) by the Department of Defense.

Read MoreWHOI Ocean Science Exhibit Center Opens for 2016 Season

The WHOI Ocean Science Exhibit Center opens for another fun and engaging summer season on April 18, 2016.

Read MoreSwarming Red Crabs Documented on Video

A research team studying biodiversity at the Hannibal Bank Seamount off the coast of Panama has captured unique video of thousands of red crabs swarming in low-oxygen waters just above the seafloor.

Read MoreR/V Neil Armstrong Arrives in Woods Hole

On April 6, the research vessel Neil Armstrong was met by a jubilant crowd at the WHOI dock as it arrived to its home port for the first time, escorted by the WHOI coastal research vessel R/V Tioga, two Coast Guard boats and fireboats from neighboring towns.

Read More