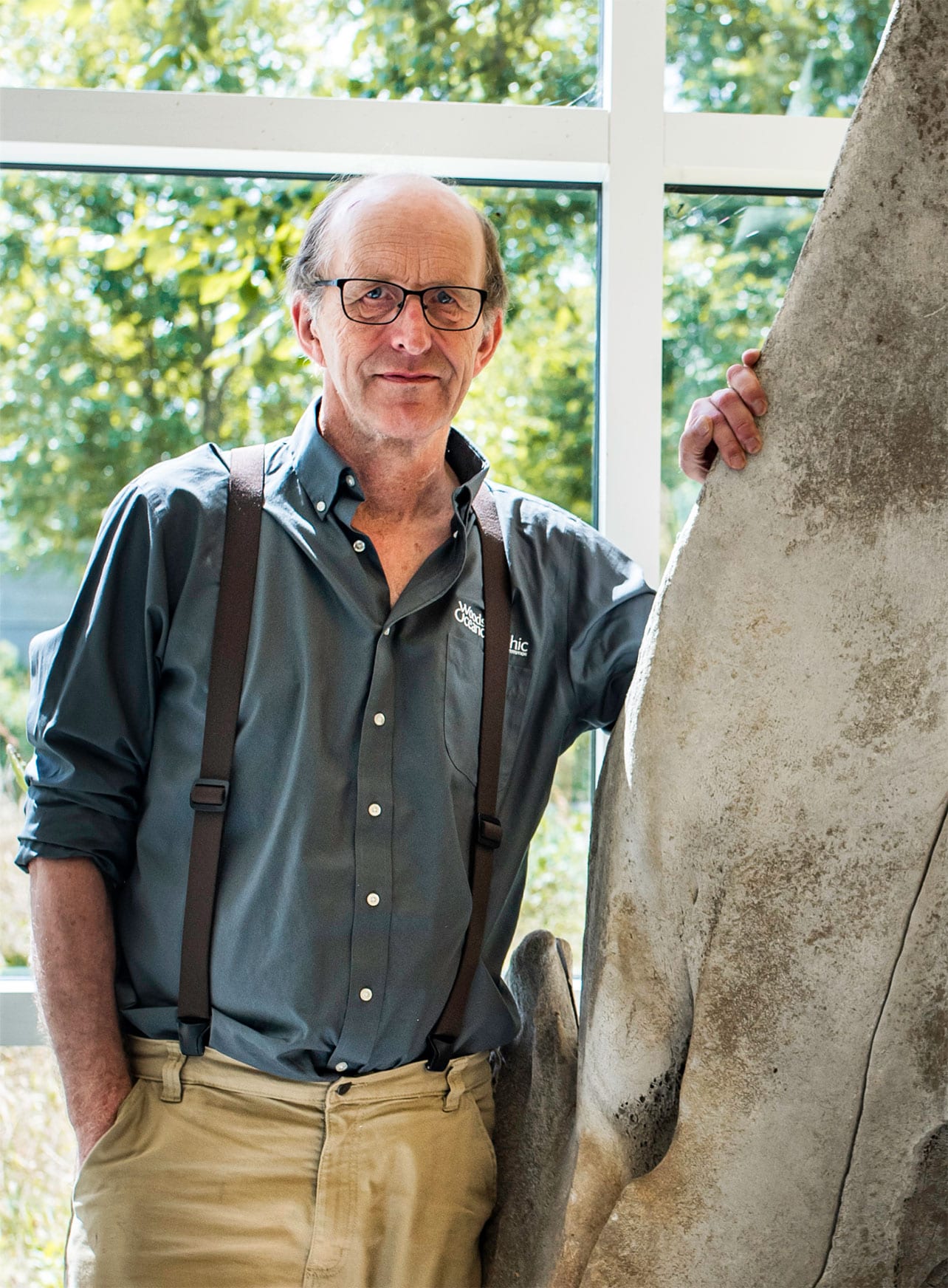

After 33 years, Michael Moore is still free to be curious at WHOI

By Daniel Hentz | September 26, 2019

Michael Moore is a senior scientist and director of the Marine Mammal Center at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. He also provides veterinary support to the Marine Mammal Rescue and Research division of the International Fund for Animal Welfare, supporting their work with stranded marine mammals on Cape Cod. In 1986, Moore joined the WHOI scientific community as a PhD student and has remained with the Institution since then. His research encompasses, among other things, the forensic analysis and accurate diagnosis of perceived human impacts on marine mammal mortalities and the improvement of large whale emergency veterinary care and technologies necessary to reduce their entanglement.

How did you come to study whales?

When I was an undergraduate as a veterinary medical student at University of Cambridge, I would go to lectures on physiology, pharmacology, etc. I started to notice that the professors, in order to keep our attention, would almost invariably tell us how the whales and dolphins did it [adapted to their environment], because they were always different. The idea of a sperm whale having the ability to dive incredible depths by holding their breath for an hour, or manatees having denser bones to counteract their buoyancy, was all quite extraordinary to me. Growing up, I always felt like the odd person out, and to me it seemed the marine mammals are also the odd ones out, so I thought maybe I should get curious about them.

What inspires you to get up every morning and do this work?

I’m really interested in the interface between humans and marine mammals, particularly the stressors that humans put on the ocean in the context of marine mammal health—for example, vessel noise and collisions, and also the fixed gear impacts of fisheries on marine mammals.

You’ve been at WHOI for more than thirty years. Why have you stayed so long? What makes WHOI different from other marine institutions?

The enormous diversity of opportunities to interact and collaborate with engineers, scientists, chemists, behaviorists, and statisticians—there’s just an endless array of resources here. WHOI has unparalleled access to the sea in the vessels that we have, but there’s also the absolute freedom to do what you want to do, to act on what drives your interest and curiosity.

Who is your ocean hero?

There was an American scientist in Canada named Jon Lien, whom I met in the late 1970s, at a time when he was trying to understand how humpback whales got caught in cod traps. He pursued the basic science of that, but also the socioeconomic impacts on the Newfoundland cod fishery. His science had as much to do with how to train fisherman in how to disentangle the whales so that they could get their gear back, as it had to do with understanding and saving the entangled animals. I really valued his dual aspect: both the conservation of the species, and the livelihood of fishermen.