The deep ocean is a cold, dark, and frankly, dangerous place for human beings. To understand our ocean fast enough to predict and manage the impacts of global change, we need to accelerate the pace at which we are exploring its vast unknowns. And that’s why we need robots to help us– and in some cases, guide us– on our quest for answers. From the icy poles to sensitive coral reefs, robots equipped with sensors empower us to understand more of the ocean than ever before.

But just what are these ocean-going robots? Dive in to find out!

The Long Range Autonomous Underwater Vehicle, or LRAUV, is designed to detect oil spills under ice. (Photo by Sean P. Whelan, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

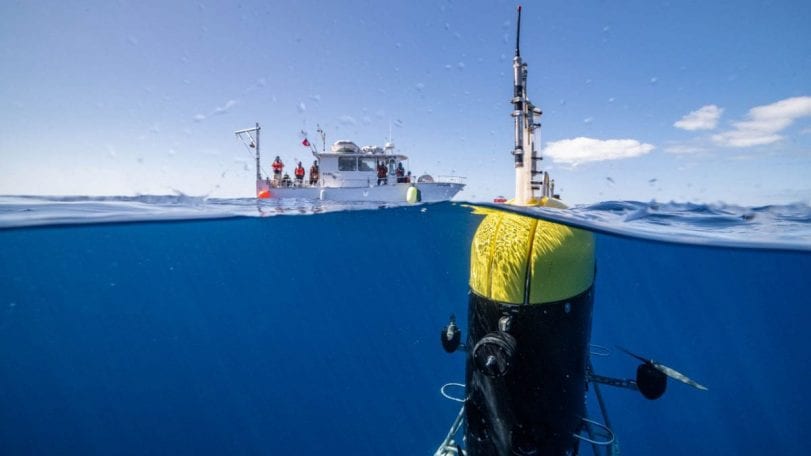

AUVs are programmable, robotic vehicles that can drift, drive, or glide through the ocean without human control. They often communicate through satellite signals or underwater acoustic beacons, sending data back to scientists on a ship or onshore in near real-time. Some AUVs can also make decisions on their own, changing their mission based on environmental data they receive through sensors. Deployed from a surface ship, AUVs allow scientists to conduct other experiments while the vehicle is off collecting data elsewhere– maximizing the amount of research that can be accomplished with expensive ship time.

Some AUVs are designed for long-range missions, which open up new horizons for rapid-response research in the most remote regions of the planet. A long range autonomous underwater vehicle (LRAUV) developed by the WHOI Scibotics Lab, in collaboration with Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, can follow a preprogrammed mission in an 1,800-kilometer (1,120-mile) radius, even under ice. It can remain under ice at depths up to 300 meters (984 feet) for weeks, sniffing out chemical anomalies and images and relaying the data back to dry land via acoustic signal and a network of remote-ocean buoys and satellites.

Gliders are winged, low-power autonomous underwater vehicles that generate forward thrust by changing their buoyancy and glide angle as they repeatedly dive and surface through the water. While vertically see-sawing their way through the water column, gliders collect oceanographic data like salinity and temperature. Some gliders can detect the presence of phytoplankton and even whales and noise-making fish like cod. Often used to carry out missions up to six months long, gliders periodically resurface to send their data back to labs on land via satellite link.

A tether links the deep-sea vehicle Jason to the research vessel Atlantis. Sensors and cameras on Jason transmit video and other data via the tether to researchers aboard ship, who relay commands back down the tether to operate the vehicle. (Photo by David Levin©2014 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

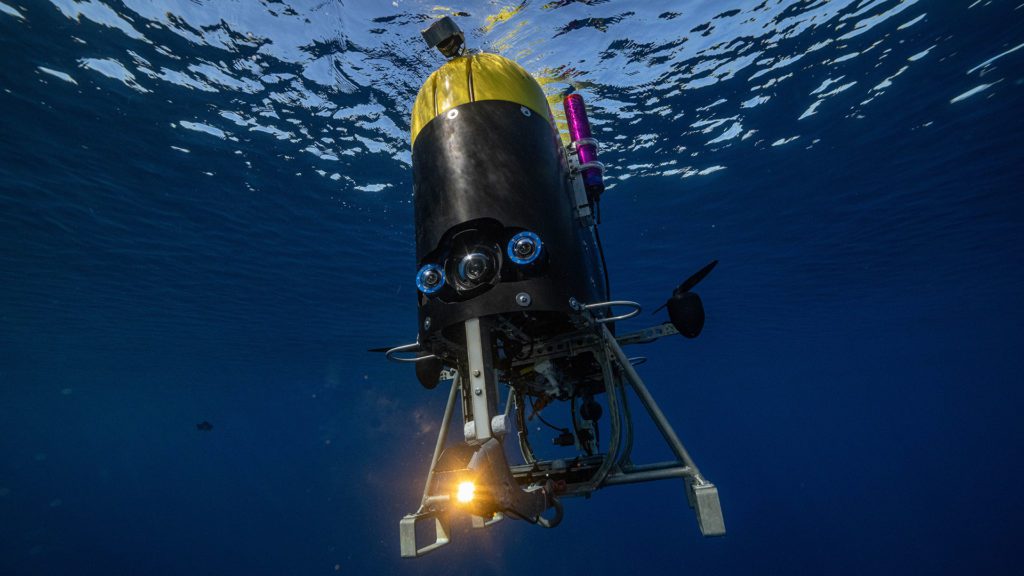

ROVs allow scientists to access the deep ocean while remaining in control of operations. Connected with a long tether (such as reinforced fiber-optic cable), ROVs receive power and commands from operators aboard a ship and send data and live video imagery in real time.

Advanced ROVs like Jason are equipped with sonars, video and still imaging systems, lighting, and numerous sampling systems. They often feature manipulator arms to collect samples of rock, sediment, or marine life to study back at the surface. They often are deployed for just a few hours, but can go on several-day missions if required.

Hybrid remotely operated vehicles (HROVs) like Nereid Under Ice (NUI) or Mesobot can be autonomous like an AUV or tethered like an ROV, giving researchers flexibility about where and how to use them.

Autonomous Surface Vessels (ASVs)

To monitor changes in a rapidly warming Arctic, scientists deploy autonomous surface vehicle ChemYak in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, where it uses an array of sensors to measure the rapid release of greenhouse gases in the spring thaw. (Photos by William Pardis, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Former WHOI physical oceanographer Dave Fratantoni inspects a Wave Glider on the deck of R/V Knorr in 2012. The Wave Glider uses wave motion to propel itself through the ocean and solar-charged batteries to power its data collection sensors. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Not all ocean robots go underwater. WHOI engineers have adapted commercially-available surface vehicles for scientific purposes. Outfitted with a suite of onboard sensors, even a motorized kayak can become a robot!

Jetyak, and a more application-specific version called Chemyak, is a modified gas-powered, jet-drive kayak that can collect samples in dangerous and difficult-to-reach places. Scientists can remotely control JetYak or program it to run autonomously on a designated course. Jetyak and Chemyak have been used to map the seafloor and measure environmental conditions of waters that are too shallow for underwater vehicles or in areas too treacherous for humans, such as the front of calving glaciers.

If Chemyak is a kayak, the Wave Glider is a paddleboard. This wave- and solor-powered ASV was adapted by WHOI engineers to take surface ocean salinity and temperature over broad areas of the open ocean. It can even act as a “mid-ocean telephone operator” to relay data from AUVs like Sentry to researchers aboard the ship, allowing the AUV to explore without surfacing.

Profiling floats are easily deployed, relatively low-cost autonomous vehicles that can remain at sea for months or years to measure changes almost anywhere across the breadth and depth of the ocean. The long-running international ARGO program maintains a fleet of about 4,000 floats that profile heat and salinity throughout the global ocean. Smaller ALAMO (Air-Launched Autonomous Micro Observer) floats can be deployed ahead of tropical storms and hurricanes to rapidly sample ocean-atmosphere interactions and improve storm intensity forecasts. After traveling to about 2,000 meters depth (1,000 meters for ALAMO), the float returns to the surface and connects with an Iridium satellite to upload data and receive any new mission instructions. This cycle repeats until the end of the float’s lifetime, usually around 4 years. The data is freely available to anyone with an Internet connection, and the broad scale of measurements has been crucial to understanding our changing ocean.

Other types of floats and drifters are used to explore ocean circulation patterns and track harmful algal blooms and sargassum.

LEARN MORE ABOUT OCEAN ROBOTS

AUVs

AUVs are programmable, robotic vehicles that, depending on their design, can drift, drive, or glide through the ocean without real-time control by human operators.

» Mesobot

» REMUS

» SeaBED

» Sentry

» Spray Glider

» Slocum Glider

ROV Jason/Medea

Jason is a remote-controlled, deep-diving vehicle that gives shipboard scientists real-time access to the sea floor. Scientists guide Jason as deep as 6,500 meters (4 miles) to explore underwater features on multi-day missions.

DIVE INTO MORE OCEAN FACTS

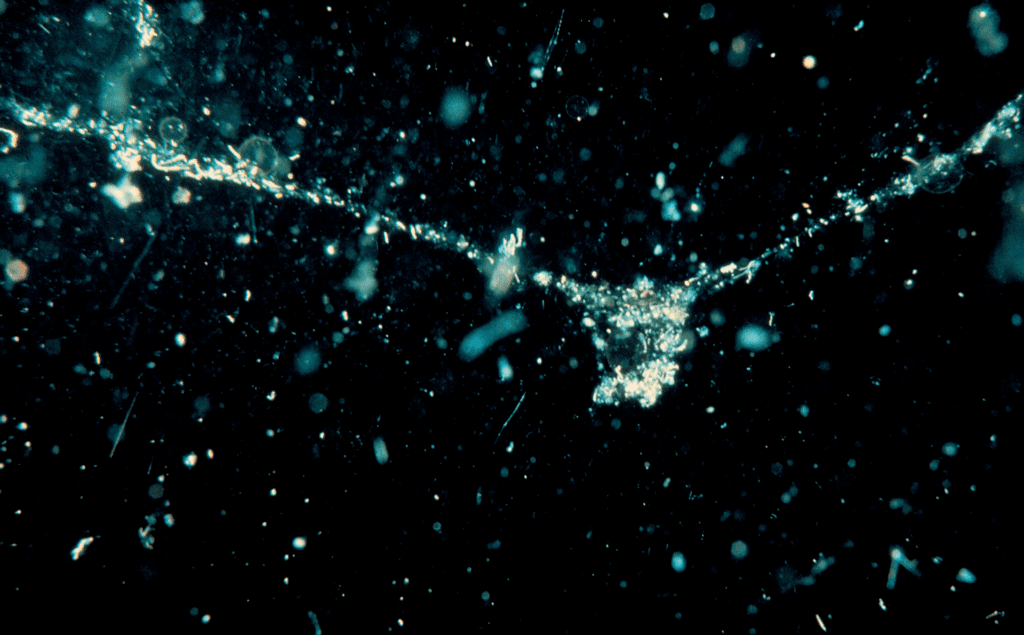

How deep do marine plastics go?

Learn how plastic pollution pervades the ocean, from surface debris to deep-sea trenches. With 390 million tons produced annually, plastic poses a significant threat, impacting marine ecosystems and organisms.

How are seashells made?

One of the most striking features of our beaches is seashells. Their whorls, curves, and shiny iridescent insides are the remains of animals. But where do they come from?

Where does all the carbon go?

Explore the ocean’s critical role in carbon sequestration and how it could be a pathway to mitigate climate change.

Why do corals bleach?

Corals have a symbiotic relationship with algae. The algae gives corals their color and provides them with food. In return, corals provide the algae with a place to live.