Shedding light on the deep, dark canyons of the Mid-Atlantic

By Evan Lubofsky | February 19, 2020

The deep-water canyons of the Mid-Atlantic Ocean—most deeper than the Grand Canyon—are teeming with life. Yet scientists have only recently begun to discover what these canyons hold.

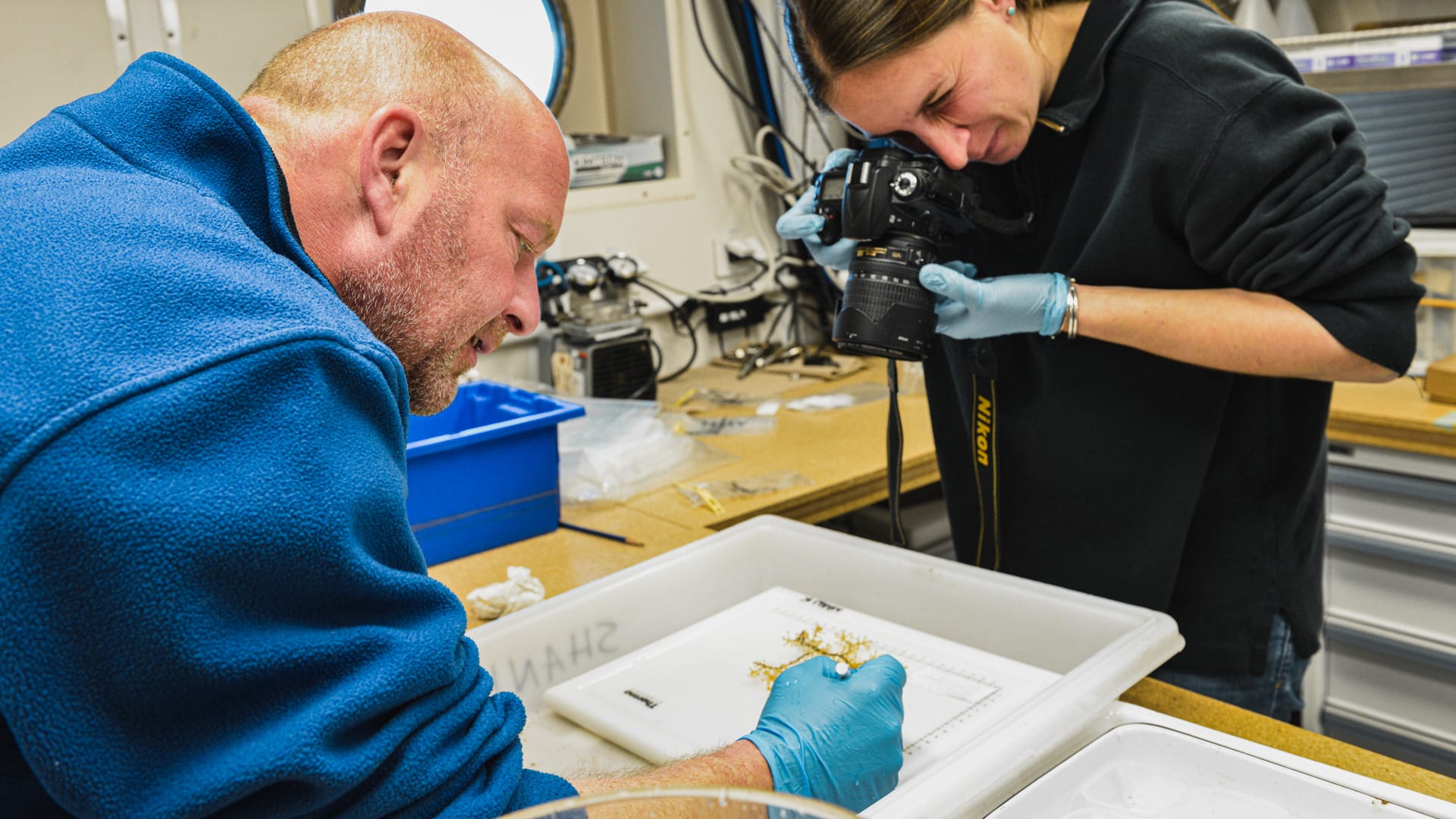

In a new report developed for the Mid-Atlantic Regional Council on the Ocean (MARCO), WHOI marine biologists Tim Shank and Taylor Heyl, along with scientists from NOAA Fisheries Service and the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science (NCCOS), have documented a significant amount of biodiversity throughout the nearly 40 canyons they’ve surveyed since 2012.

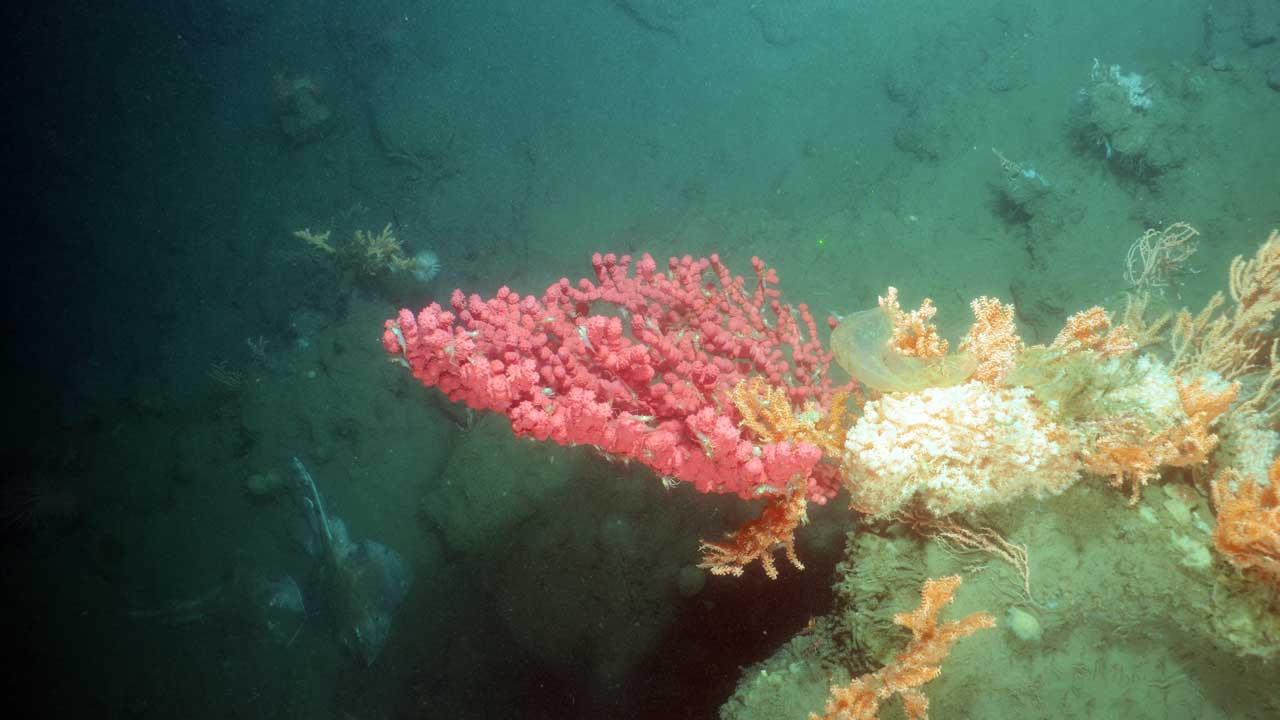

The surveys, conducted with WHOI’s ship-tethered digital camera system known as TowCam, have unveiled more than 45 fish species, as well as 13 types of hard and soft corals.

We caught up with Shank to hear more about these deep-sea ecosystems and his thoughts on how they can be managed sustainably in the face of a changing climate and increased human pressures.

Why are the Mid-Atlantic Ocean canyons so important?

The Mid-Atlantic canyons are so close to us here in the Northeast, and represent a very local connection between the deep sea and shallow water. The ecosystems there are incredibly productive: we’ve found at least 75 species of corals there, and they host an amazing amount of biodiversity. This is partly due to the fact that deep currents flowing through the canyons bring up lots of nutrients from the deep sea. But it’s not just productive from a biomass standpoint; these canyons attract large aggregations of whales, dolphins, sharks, and sea birds, and support all of the region’s major fisheries.

Paragorgia bubblegum and Acanthogorgia corals on a rock wall in Wilmington Canyon at a depth of 512 meters. (Photo courtesy of Tim Shank, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

In the report, you mention the corals in the Mid-Atlantic are extremely vulnerable. Why is that?

The corals in the Mid-Atlantic are under stress from warming ocean temperatures and ocean acidification, much like the corals found in the Caribbean, Florida, and other parts of the world. During our surveys, we’ve also seen fishing line wrapped around some of the corals and lots of trash including plastic bags and containers, pieces of metal, cans, bottles, and crab pots. We have seen human debris in every canyon we've surveyed.

The corals themselves have certain properties that make them particularly vulnerable. They can be be extremely slow growing—we’re talking microns per year. So, these corals won’t grow back quickly and if they’re damaged, based on our observations, we likely wouldn’t see new colonization happen in our lifetimes.

You’ve studied corals from around the globe. Did anything surprise you about the corals you discovered in these particular canyons?

One really interesting thing we found is that the slope of the canyon walls seems to have a direct effect on the presence of corals. Any time we saw more than a 45-degree slope, we found corals, many living in the cracks and crevices of steep walls.

Also, the diversity and abundance of corals were remarkably higher in the “incised” canyons—those that cut into the continental slope—versus those that didn’t.

Why is it so important to study ecosystems in these deep-ocean canyons?

This part of the Northwest Atlantic is warming, and predicted to warm three times faster than anywhere in the Atlantic. This will not only alter current directions and speed, but also dramatically impact the very survival of highly intolerant corals. In essence, these corals in the canyons are our canaries in the coal mine. It is important to learn how diverse coral ecosystems respond to oceanographic change. If these protected areas become smaller or are opened up completely to activities that disturb these ecosystems, you quickly lose the ability to understand the impacts. And if we don’t gather and provide enough information, it will be impossible to manage and protect these important ecosystems.

Where do you see the greatest gaps in our knowledge about the Mid-Atlantic canyons?

Right now, we’re still in the exploration phase of research—trying to understand what fauna are living in these canyons, and what are their habitats. We have just conducted an in-depth study to identify the corals and fish and match them up with their respective habitat types. We have determined the types of corals that live on sheer walls, along the margins of walls and in sediments. This will help the Fisheries Management Councils, government agencies, and scientists predict what might be living in other ocean canyons (there are well over 50) that we currently have not explored.

We also want to tackle questions like whether certain habitat-forming species are genetically connected among and between canyons, and how the corals function to benefit society by supporting fisheries, food supply, biodiversity, resilience, and biomedical applications.

The other big question we need to look at is how corals in the Mid-Atlantic will fare in the face of climate change. The water there is projected to heat up faster than anywhere else in the Atlantic over the next 50 years. We are now in an urgent race to capture environmental data and deep coral health information to observe how the impacts of warming alter coral species and the high diversity they support.

The data collection at sea was supported by the NOAA Deep-Sea Coral Research and Technology Program, with project partner Martha Nizinski, NOAA NMFS; data analyses was supported by the Mid-Atlantic Regional Ocean Council, with project partners Brian Kinlan and Matt Poti; sea-going technical support was provided by WHOI's MISO Facility.