Marine Chemistry & Geochemistry

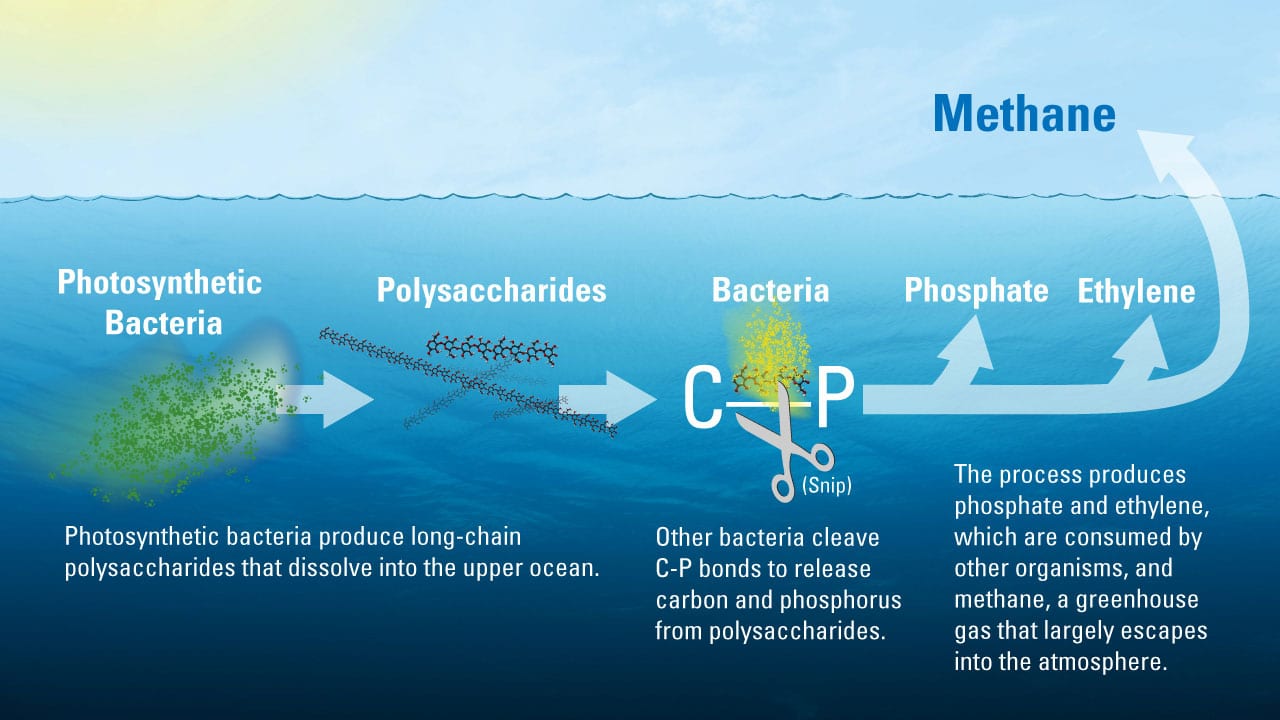

New Study Explains Mysterious Source of Greenhouse Gas Methane in the Ocean

A new study may have cracked the longstanding ‘marine methane paradox,’ finding that the answer may lie in the complex ways that bacteria break down substances excreted into seawater by living organisms.

Read MoreWHOI Scientist Receives Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation Award

The Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation selected Mak Saito, a biogeochemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), as one of eight awardees of a 2016 Postdoctoral Program in Environmental Chemistry grant.

Read MoreAs Bay Warms, Harmful Algae Bloom

Warming coastal waters off southern Massachusetts are worsening the effects of pollution from septic systems, wastewater treatment plants, and fertilizer runoff—and causing a rise in harmful algal blooms. Researchers at…

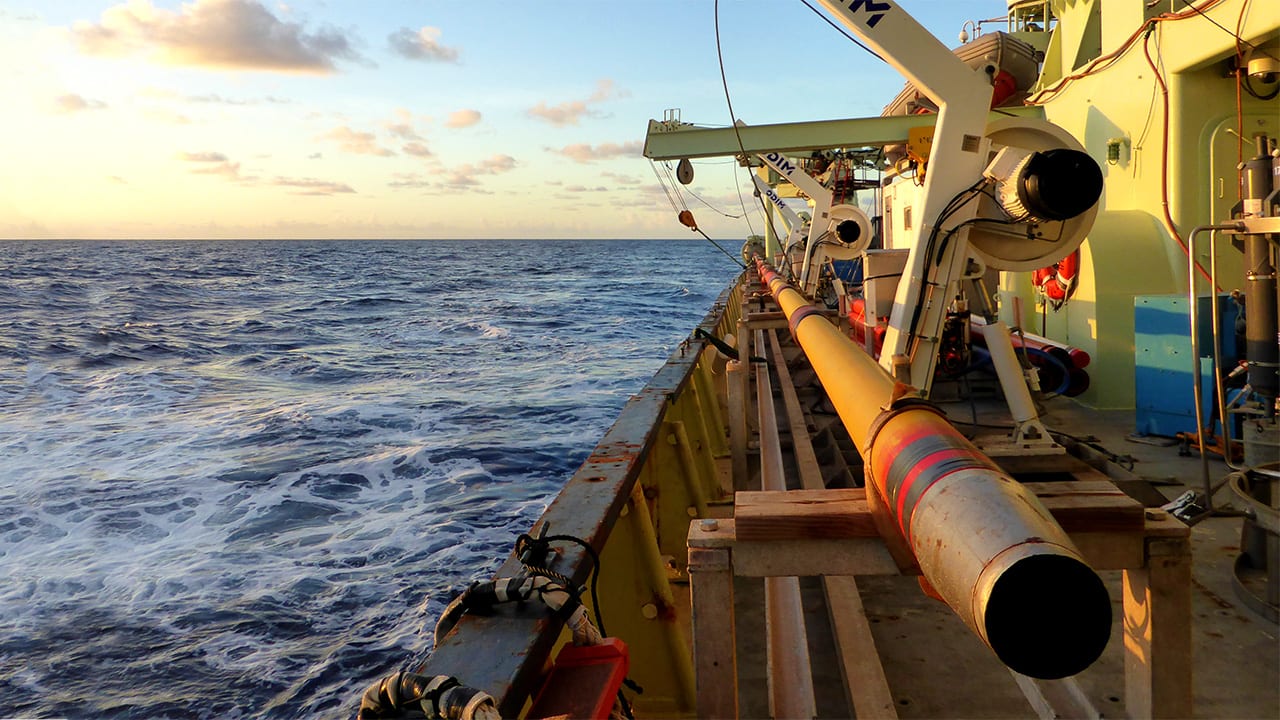

Read MoreCoral Coring

Off a small island in the Chagos archipelago in the Indian Ocean, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) biogeochemists Konrad Hughen and Colleen Hansel use a special underwater drill to take…

Read MoreA Faster Way to Better Reactions

Finding new chemical reactions to synthesize commercial products more efficiently is big business and a major source of innovation. A new study offers a way to make the search faster, cheaper, and greener.

Read MoreFukushima Site Still Leaking After Five Years, Research Shows

Five years after the Fukushima accident, scientific data about the levels of radioactivity in the ocean off our shores are available publicly thanks to ongoing efforts of independent researchers, including WHOI radiochemist Ken Buesseler, who has led the effort to create and maintain an ocean monitoring network along the U.S. West Coast.

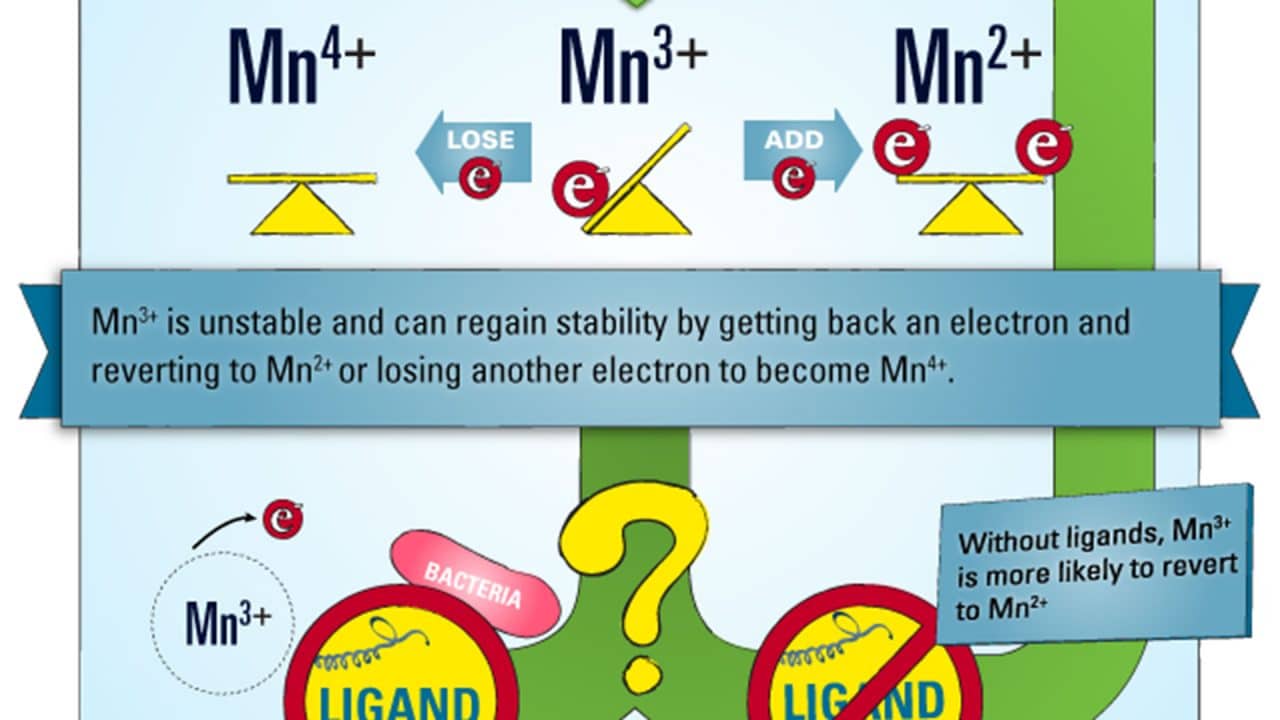

Read MoreTwo Chemical Roads Diverge in an Open Ocean

An infographicon biomineralization

Read MoreMinerals Made by Microbes

Some minerals actually don’t form without a little help from microscopic organisms, using chemical processes that scientists are only beginning to reveal.

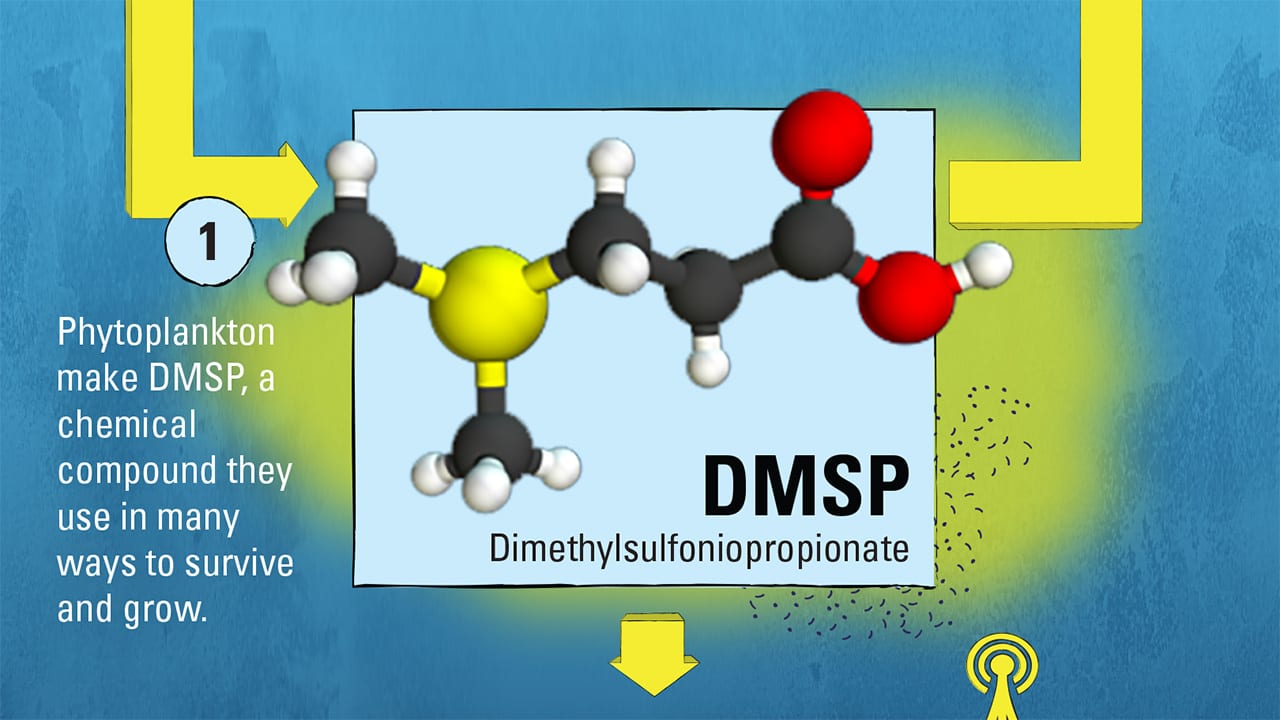

Read MoreA Mighty Mysterious Molecule

What gives sea air its distinctive scent? A chemical compound called dimethylsulfide. In a new study, WHOI scientists show that the compound may also be used by marine microbes to communicate with one another.

Read MoreSpecks in the Spectrometer

Mass spectrometer facilities can be a rite of passage for scientists—as well as for the samples analyzed inside the mass specs.

Read MoreHigher Levels of Fukushima Cesium Detected Offshore

Scientists monitoring the spread of radiation in the ocean from the Fukushima nuclear accident report finding an increased number of contaminated sites off the US West Coast, along with the highest detection level to date, from a sample collected about 1,600 miles west of San Francisco. The level of cesium in the sample is 50 percent higher than other samples collected, but is still more than 500 times lower than US government safety limits for drinking water and well below limits of concern for direct exposure while swimming, boating, or other recreational activities.

Ken Buesseler, a marine radiochemist with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and director of the WHOI Center for Marine and Environmental Radioactivity, was among the first to begin monitoring radiation in the Pacific, organizing a research expedition to the area just three months after the start of the ongoing accident. Through a citizen science sampling effort, Our Radioactive Ocean, as well as research funded by the National Science Foundation, Buesseler and his colleagues are using sophisticated sensors to measure minute levels of ocean-borne radioactivity from Fukushima. In 2015, they have added more than 50 new sample locations in the Pacific to the more than 200 previously collected and posted on the Our Radioactive Ocean web site.

Read MoreEarth’s Riverine Bloodstream

Like blood in our arteries in our body, water in rivers carry chemical signals that can tell us a lot about how the entire Earth system operates.

Read MoreTracking a Trail of Carbon

Lake Titicaca in the Andes Mountains of South America is an extraordinary place to explore ancient human civilization, Earth’s climate history, and the flow of carbon through our planet.

Read MoreClimate Change Will Irreversibly Force Key Ocean Bacteria into Overdrive

A new study from University of Southern California and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) shows that changing conditions due to climate change could send Tricho into overdrive with no way to stop – reproducing faster and generating lots more nitrogen. Without the ability to slow down, however, Tricho has the potential to gobble up all its available resources, which could trigger die-offs of the microorganism and the higher organisms that depend on it.

Read MoreEvidence of Ancient Life Discovered in Mantle Rocks Deep Below the Seafloor

Ancient rocks harbored microbial life deep below the seafloor, reports a team of scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), Virginia Tech, and the University of Bremen. This new…

Read MoreShort-circuiting the Biological Pump

The ocean has been sucking up the heat-trapping carbon dioxide (CO2) building up in our atmosphere—with a little help from tiny plankton. Like plants on land, these plankton convert CO2…

Read MoreExamining the Fate of Fukushima Contaminants

An international research team reports results of a three-year study of sediment samples collected offshore from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in a new paper published August 18, 2015, in the American Chemical Society’s journal, Environmental Science and Technology. The research aids in understanding what happens to Fukushima contaminants after they are buried on the seafloor off coastal Japan.

Read MoreRiver Buries Permafrost Carbon at Sea

As temperatures rise, some of the carbon dioxide stored in Arctic permafrost meets an unexpected fate—burial at sea. As many as 2.2 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) per year are swept along by a single river system into Arctic Ocean sediment, according to a new study led by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) researchers and published today in Nature. This process locks away the greenhouse gas and helps stabilize the earth’s CO2 levels over time, and it may help scientists better predict how natural carbon cycles will interplay with the surge of CO2 emissions due to human activities.

“The erosion of permafrost carbon is very significant,” says WHOI Associate Scientist Valier Galy, a co-author of the study. “Over thousands of years, this process is sequestering CO2 away from the atmosphere in a way that amounts to fairly large carbon stocks. If we can understand how this process works, we can predict how it will respond as the climate changes.”

Permafrost—the permanently frozen ground found in the Arctic and Antarctic and in some alpine regions—is known to hold billions of tons of organic material, including vast stores of CO2. Amid concerns about rising Arctic temperatures and their impact on permafrost, many researchers have directed their efforts to studying the permafrost carbon cycle—the processes through which the carbon circulates between the atmosphere, the soil and surface (the biosphere), and the sea. Yet how this cycle works and how it responds to the warming, changing climate remains poorly understood.

Galy and his colleagues from Durham University, the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, the NERC Radiocarbon Facility, Stockholm University, and the Universite Paris-Sud set out to characterize the carbon cycle in one particular piece of the Arctic landscape—northern Canada’s Mackenzie River, the largest river flowing into the Arctic Ocean from North America and that ocean’s greatest source of sediment. The researchers hypothesized that the Mackenzie’s muddy water might erode thawing permafrost along its path and wash that biosphere-derived material and the CO2 within it into the ocean, preventing the release of that CO2 into the atmosphere.

Read MoreJohn W. Farrington Named 2015 American Geophysical Union Fellow

John W. Farrington of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) has been elected a fellow of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).Farrington, Dean emeritus and an emeritus member in the Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry Department, is among 60 new fellows who will be honored for “exceptional scientific contributions and attained acknowledged eminence in the fields of Earth and space sciences.”

Read MoreMaking Organic Molecules in Hydrothermal Vents in the Absence of Life

In 2009, scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution embarked on a NASA-funded mission to the Mid-Cayman Rise in the Caribbean, in search of a type of deep-sea hot-spring or hydrothermal vent that they believed held clues to the search for life on other planets. They were looking for a site with a venting process that produces a lot of hydrogen because of the potential it holds for the chemical, or abiotic, creation of organic molecules like methane – possible precursors to the prebiotic compounds from which life on Earth emerged.

For more than a decade, the scientific community has postulated that in such an environment, methane and other organic compounds could be spontaneously produced by chemical reactions between hydrogen from the vent fluid and carbon dioxide (CO2). The theory made perfect sense, but showing that it happened in nature was challenging.

Now we know why: an analysis of the vent fluid chemistry proves that for some organic compounds, it doesn’t happen that way.

New research by geochemists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, published June 8 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is the first to show that methane formation does not occur during the relatively quick fluid circulation process, despite extraordinarily high hydrogen contents in the waters. While the methane in the Von Damm vent system they studied was produced through chemical reactions (abiotically), it was produced on geologic time scales deep beneath the seafloor and independent of the venting process. Their research further reveals that another organic abiotic compound is formed during the vent circulation process at adjacent lower temperature, higher pH vents, but reaction rates are too slow to completely reduce the carbon all the way to methane.

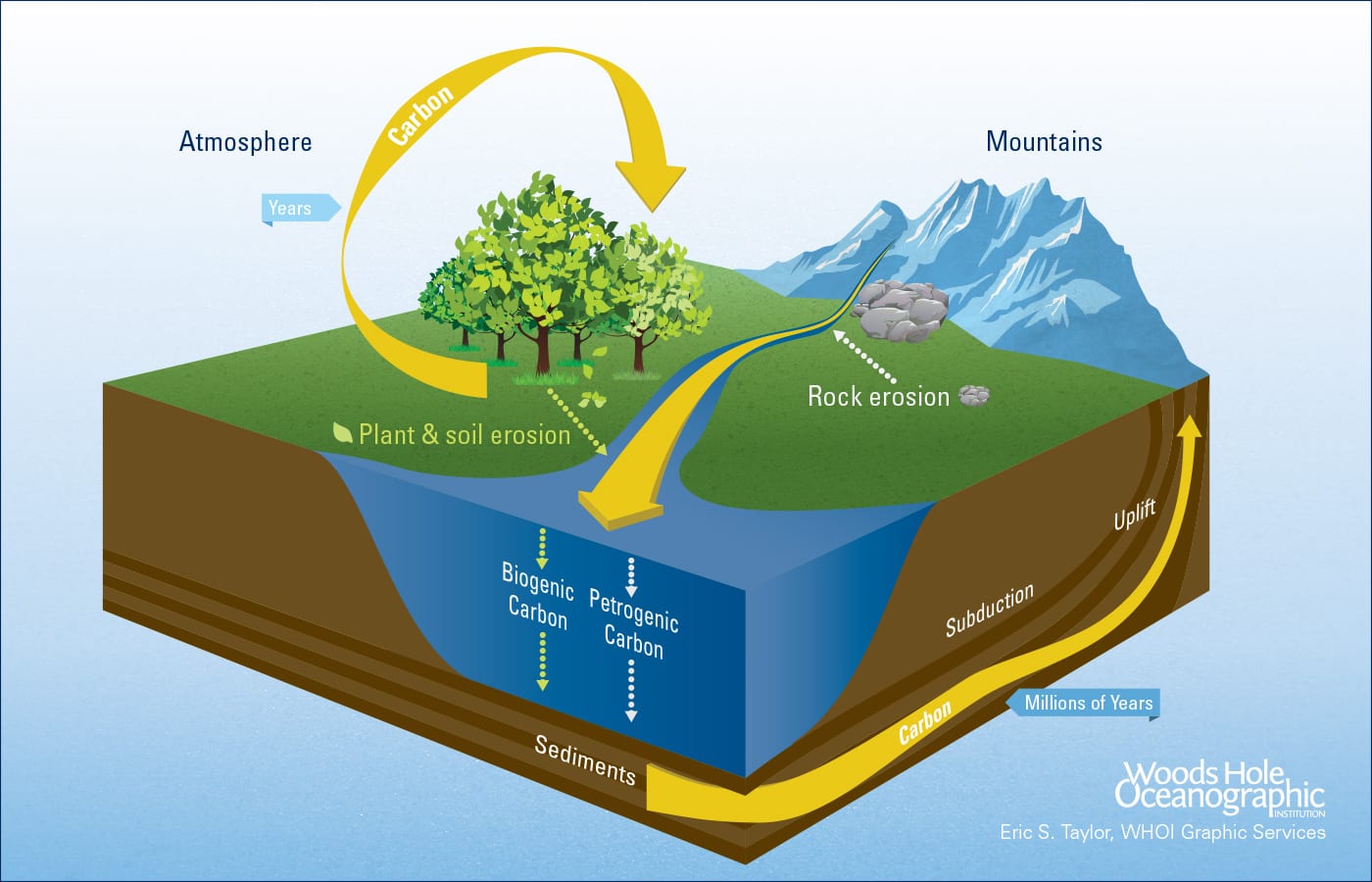

Read MoreStudy Reveals How Rivers Regulate Global Carbon Cycle

Humans concerned about climate change are working to find ways of capturing excess carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and sequestering it in the Earth. But Nature has its own methods for the removal and long-term storage of carbon, including the world’s river systems, which transport decaying organic material and eroded rock from land to the ocean.

While river transport of carbon to the ocean is not on a scale that will bail humans out of our CO2 problem, we don’t actually know how much carbon the world’s rivers routinely flush into the ocean – an important piece of the global carbon cycle.

But in a study published May 14 in the journal Nature, scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) calculated the first direct estimate of how much and in what form organic carbon is exported to the ocean by rivers. The estimate will help modelers predict how the carbon export from global rivers may shift as Earth’s climate changes.

Read MoreSecuring the Supply of Sea Scallops for Today and Tomorrow

Good management has brought the $559 million United States sea scallop fishery back from the brink of collapse over the past 20 years. However, its current fishery management plan does not account for longer-term environmental change like ocean warming and acidification that may affect the fishery in the future. A group of researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, and Ocean Conservancy hope to change that.

Read MoreOcean Bacteria Get ‘Pumped Up’

In a new study published April 27 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and their colleague from Rutgers University discovered a surprising new short-circuit to the biological pump. They found that sinking particles of stressed and dying phytoplankton release chemicals that have a jolting, steroid-like effect on marine bacteria feeding on the particles. The chemicals juice up the bacteria’s metabolism causing them to more rapidly convert organic carbon in the particles back into CO2 before they can sink to the deep ocean.

Read More

Trace Amounts of Fukushima Radioactivity Detected Along Shoreline of British Columbia

Scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) have for the first time detected the presence of small amounts of radioactivity from the 2011 Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident in a seawater sample from the shoreline of North America. The sample, which was collected on February 19 in Ucluelet, British Columbia, with the assistance of the Ucluelet Aquarium, contained trace amounts of cesium (Cs) -134 and -137, well below internationally established levels of concern to humans and marine life.

Read More