WHOI Scientists Contribute to Study on Impact to Coral Communities from Deepwater Horizon Spill

March 26, 2012

Six scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) have contributed to a new report finding “compelling evidence” that the Deepwater Horizon oil spill has impacted deep-sea coral communities in the Gulf of Mexico. The study, published the week of March 26 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, utilized all of the deep-sea robotic vehicles of the WHOI-operated National Deep Submergence Facility—the three-person submersible Alvin, the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason, and the autonomous vehicle Sentry – to investigate the corals, and employed comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography to track the source of petroleum hydrocarbons found.

Lead author Helen White, an assistant professor of chemistry at Haverford College and a graduate of the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in oceanography, was part of a diverse team of researchers, led by Charles Fisher from Penn State University, that included Erik Cordes from Temple University and Tim Shank and Chris German from WHOI. Fisher, Cordes, Shank, and German are co-authors of the study, along with WHOI’s Chris Reddy, Bob Nelson, Rich Camilli, and Walter Cho (now with Gordon College) and six other scientists from Penn State, Temple, and the U.S. Geological Survey.

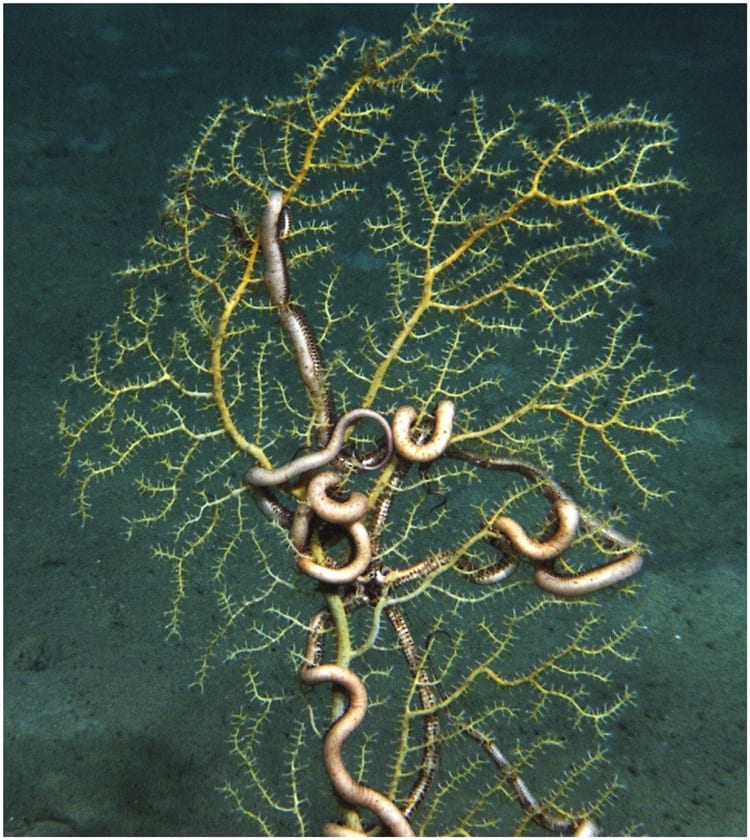

“These corals exhibited varying levels of stress, from bare skeleton, tissue loss, to excess mucous production, all associated with a covering of brown flocculent material,” said Tim Shank, a WHOI biologist and an expert in life in the deep ocean. “This was 11 kilometers southwest of the well and underscores the magnitude of the release and potential impact to other deep-water ecosystems. Corals like these in particular serve as hosts to other animals—crabs, shrimp and brittle stars that may be impacted by the loss of their habitat.”

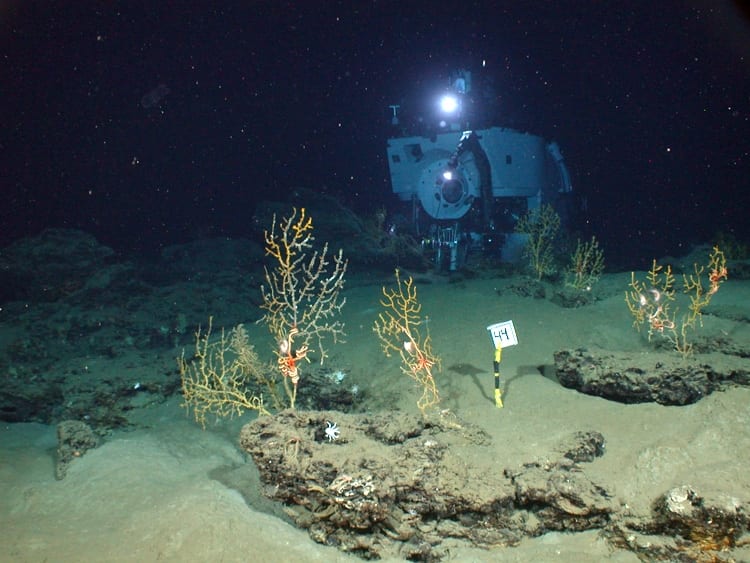

The study grew out of a previously scheduled research cruise to the Gulf led by Fisher in late October 2010—approximately six months after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. This expedition was part of an ongoing study funded by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Ocean Exploration and Research program. Using the ROV Jason, the team examined nine sites 20 km from the Macondo well and found deep-water coral communities unharmed. However, when the ROV explored an area 11 km to the SW of the spill site at a depth of 4,300 feet, the team was surprised to discover numerous coral communities covered in a brown flocculent material and showing signs of tissue damage.

“We discovered the site during the last dive of the three-week cruise,” said Fisher, a biologist and the chief scientist of this mission. “As soon as the ROV got close enough to the community for the corals to come into clear view it was clear to me that something was wrong at this site. I think it was too much white and brown, and not enough color on the corals and brittle stars. Once we were close enough to zoom in on a few colonies, there was no doubt that this was something I had not seen anywhere else in the Gulf: an abundance of stressed corals, showing clear signs of a recent impact. This is exactly what we had been on the lookout for during all dives, but hoping not to see anywhere.”

“When we sampled small parts of these corals, some of the tissue sloughed off. We’d never seen anything like this,” said Shank. “Some of the brittle stars were lacking color, and tightly wrapped around the coral.”

Despite the coral communities’ proximity to the Macondo well, at the time, the visual damage could not be directly linked to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Determined to find answers, the team set out barely a month later on a second cruise to the Gulf – a rare opportunity to return so quickly made possible by the National Science Foundation’s RAPID Collaborative Research grant program.

Joining this second research cruise, again headed by Fisher, was Helen White, whose expertise as a geochemist was key to the interdisciplinary effort. “It is easy to see the impact of oil on surface waters, coastlines and marine life, but this was the first time we were diving to the seafloor to examine the effects on deep sea ecosystems,” said White.

To examine the deep water, the team employed the AUV Sentry to map and photograph the ocean floor and the deep submergence vehicle Alvin to get a better look at the distressed corals.

“This research drew upon all the resources of the National Deep Submergence Facility to complete the work,” said Chris German, the chief scientist for deep submergence at WHOI. “This is a great exemplar of why we need such a diverse array of assets, not just for fundamental research but also to enable scientists to respond, rapidly, independently and objectively, at a time of national need.”

During six dives in Alvin, the team collected sediments and samples of the corals and filtered the brown material off of the corals for analysis. “Collecting samples from the deep ocean is incredibly challenging, and Alvin is crucial to this kind of work,” said White. “As a geochemist, my primary aim in this research was to determine the composition of the brown flocculent material covering the corals and the source of any petroleum hydrocarbons present.”

Because oil can naturally seep from cracks in the sea floor of the Gulf, pinpointing the source of petroleum hydrocarbons in Gulf samples can be challenging to scientists, especially since oil is comprised of a complex mixture of different chemical compounds. However, there are often slight differences in oils that can be used to trace their origin. To identify the oil found in the coral communities, White worked with WHOI marine chemist Christopher Reddy and research specialist Robert Nelson using an advanced technique called comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography, which was pioneered at WHOI by Reddy and Nelson for use in oil spill research. The method provided invaluable evidence on the source of the oil.

This exacting petroleum analysis coupled to the analysis of 69 images from 43 individual corals at the site, performed by Pen-Yuan Hsing, a graduate student of Charles Fisher’s at PSU, yielded strong evidence that the coral communities were impacted by oil from the Macondo well spill.

“We don’t know the long-term impacts on these corals. We don’t know if the living corals will recover or not. We hope our continued monitoring of this site, including time-lapse imaging, will give us insight into the potential for long-term recovery,” said Shank, who is currently exploring the diversity and distribution of deep-sea habitats and marine life in the northern Gulf of Mexico aboard NOAA’s Okeanos Explorer.

Reddy stated that he was interested in why and how far the oil travelled and spread along the seafloor. This result adds to other studies that have shown that the Deepwater Horizon disaster affected the seafloor, the seawater with plumes of hydrocarbon-rich water, surface slicks, and vapors in the atmosphere as well as oiled beaches and marshes.

“Ongoing work in the Gulf will improve our understanding of the resilience of these isolated communities and the extent to which they are affected by human activity. Oil had a visible effect on these corals and it is important to determine if they can rebound,” said White.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the oceans and their interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the oceans’ role in the changing global environment. For more information, please visit www.whoi.edu.