Underwater Robot Makes History Crossing the Gulf Stream

November 5, 2004

Like the sailing vessel used by Captain Joshua Slocum to sail solo around the world 100 years ago, another ocean-going vehicle is making history. A small ocean glider named Spray is the first autonomous underwater vehicle, or AUV, to cross the Gulf Stream underwater, proving the viability of self-propelled gliders for long-distance scientific missions and opening new possibilities for studies of the oceans.

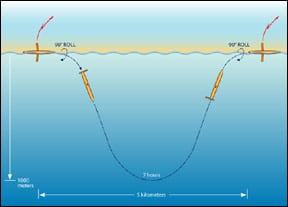

Launched September 11, 2004, about 100 miles south of Nantucket Island, Mass., the two-meter- (6-foot)-long orange glider with a four-foot wingspan looks like a model airplane with no visible moving parts. It has been slowly making its way toward Bermuda some 600 miles to the south of Cape Cod at about one-half knot, roughly half a mile an hour or 12 miles per day, measuring various properties of the ocean as it glides up to the surface and then glides back down to 1,000-meters depth (3,300 feet) three times a day. Scientists recovered the vehicle this week north of Bermuda.

Every seven hours Spray spends about 15 minutes on the surface to relay its position and information about ocean conditions, such as temperature, salinity and pressure, via satellite back to Woods Hole, Mass., and San Diego, where scientists Breck Owens from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and Russ Davis and Jeff Sherman of Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, track its progress.

It has been an adventure-filled voyage. After two false starts this summer, when malfunctioning equipment cut earlier missions short and the scientists had to recover the vehicle after a few days at sea, the 112-pound glider was launched (with fingers crossed) in September from the research vessel Cape Hatteras.

Like parents giving the car keys to a teenage driver for the first time, Owens, Davis and Sherman were apprehensive yet confident that the vehicle would reach Bermuda. The first week went smoothly, but when the vehicle began to cross the Gulf Stream, where surface currents can exceed six mph across the Stream’s 30-60-mile width, Spray was taken for a fast ride back to the north. “We lost almost two weeks’ progress in just two days,” noted Sherman. The ability to communicate with the vehicle and send commands enabled the scientists to give it a new course each time it surfaced, and Spray eventually crossed the Gulf Stream and was back on track.

“It has been exciting, to say the least,” Owens said. “We have just completed a track across the Gulf Stream (Learn more about Spray at WHOI’s Ocean Library site and Script’s Spray site) and proved we can use gliders to monitor circulation patterns and major currents.”

Spray has a range of 6,000 kilometers, or about 3,500 miles, which means it could potentially cross the Atlantic Ocean and other ocean basins.

“The key,” said Davis, “is that Spray can stay at sea for months at relatively low cost, allowing us to observe large-scale changes under the ocean surface that might otherwise go unobserved.”

Being able to communicate with the vehicle and change course or change the information it is collecting while at sea is a big step forward in the ability to gather information in the ocean.

“We envision having fleets of gliders in operation in a few years,” Owens said. “It could change the very nature of the kinds of questions we can ask about how the ocean works.”

Spray glides up and down through the water on a pre-programmed course by pumping one liter (about four cups) of mineral oil between two bladders, one inside the aluminum hull and the other outside. By changing the volume of the glider, making it denser or lighter than the surrounding water, the vehicle floats up and sinks down while wings provide lift to drive the vehicle forward. Batteries power buoyancy change, onboard computers and other electronics.

The glider records its position at the beginning and the end of each dive by rolling on its side to expose a Global Positioning System (GPS) antenna embedded in the right wingtip. Researchers obtain data from the glider and send new instructions to it using a satellite phone system and an antenna embedded in the left wingtip.

Sensors on the glider can be changed for each mission. For the mission from Cape Cod to Bermuda, the Spray glider is equipped with a CTD (for conductivity, temperature and depth) instrument that measures temperature, salinity and pressure, and an optical sensor that measures turbidity in the water, which is related to biological productivity.

For the next mission in early 2005, the glider will make a round trip between Woods Hole, Mass., and Bermuda. For future missions it will also be equipped with an Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP) to give vertical profiles of current speed and velocity. In the not-too-distant future, Owens and Davis expect that the gliders will be equipped with an entire suite of sensors that indicate the presence of dissolved oxygen, carbon dioxide, alkalinity and nutrients in the water.

The idea for developing a robotic glider like Spray that could travel in the ocean gathering data over long periods came 15 years ago from the late Henry Stommel, a scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution known for his contributions to understanding the dynamics of ocean currents, especially the Gulf Stream. Stommel honored the first man to sail around the world alone, Joshua Slocum, by naming his idea the Slocum Mission. Slocum departed Boston on April 24,1895, on his three-year circumnavigation in Spray, a sloop he rebuilt himself. The new underwater glider is called Spray to show its lineage from Stommel’s idea and Slocum’s brave voyage.

Sherman, Davis and Owens developed the Spray glider with support from the Office of Naval Research. Additional sensor development was funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Observations Program. The Gulf Stream project is funded by the National Science Foundation.

“Spray gliders can look at entire sections of ocean basins, like the North Atlantic, or serve as virtual moorings by keeping station at a single point,” Owens said. “Unlike humans, who need to stop for breaks, gliders can carry out missions from several weeks to as long as six months. They are fairly inexpensive to build and easy to operate. We are looking forward to the day we can routinely send gliders out on missions from the comfort of our laboratories or even our homes ashore.”

While gratified to have their instrument complete its voyage, the developers of Spray are mindful that they are just at the start of a new era of autonomous ocean sampling made possible by microelectronics and satellite navigation and communication. “Oceanographic gliders are now at the stage similar to the start of aviation,” Sherman said. “Today’s accomplishments seem remarkable, but in years to come they will be commonplace, and one will wonder what the big deal was all about.”

WHOI is a private, independent marine research and engineering, and higher education organization located on Cape Cod in Falmouth, MA. Its primary mission is to understand the oceans and their interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the ocean’s role in the changing global environment. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, the Institution is organized into five scientific departments, interdisciplinary research institutes and a marine policy center, and conducts a joint graduate education program with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Scripps Institution of Oceanography, at the University of California, San Diego, is one of the oldest, largest, and most important centers for global science research and graduate training in the world. The National Research Council has ranked Scripps first in faculty quality among oceanography programs nationwide. The scientific scope of the institution has grown since its founding in 1903 to include biological, physical, chemical, geological, geophysical, and atmospheric studies of the earth as a system. Hundreds of research programs covering a wide range of scientific areas are under way today in 65 countries. The institution has a staff of about 1,300, and annual expenditures of approximately $140 million from federal, state, and private sources. Scripps operates one of the largest U.S. academic fleets with four oceanographic research ships and one research platform for worldwide exploration.

Images are available upon request. Please contact the WHOI Media Relations Office at media@whoi.edu or call 508-289-3340