Float 312, Where Are You?

In one week, people found two rarely seen ocean instruments

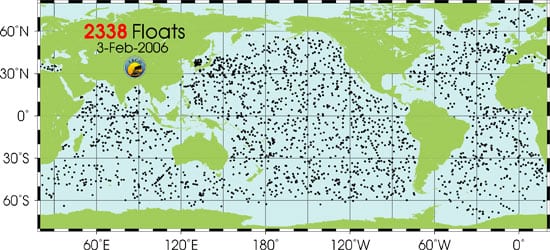

The ocean is so enormous, even a fleet of 2,338 ocean-monitoring instruments can sail into it and go largely unnoticed. That’s what floats 312 and 393 were doing until something extraordinary happened: People found them.

“To have folks stumble on these two in one week is a real surprise,” said Jim Valdes, an engineer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who designs and builds floats.

During the past six years, scientists have been releasing 5-foot-long, torpedo-shaped floats throughout the ocean—part of an international program called Argo. The instruments mostly drift at depths of 5,900 feet (1,800 meters). Once a week or so, they poke their skinny black antennas above the surface for about 12 hours to transmit temperature and salinity data to shore via satellite and then submerge again.

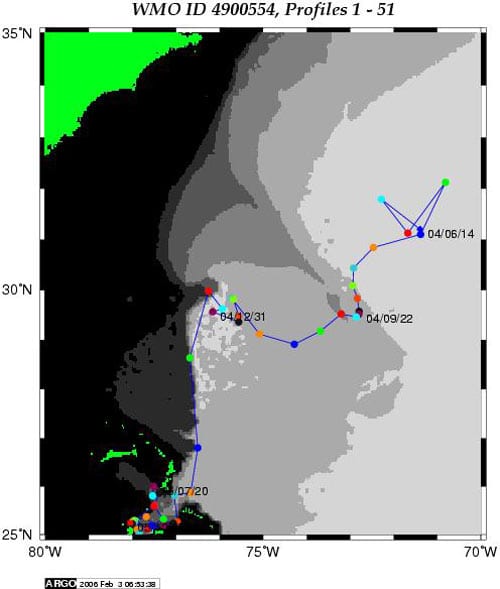

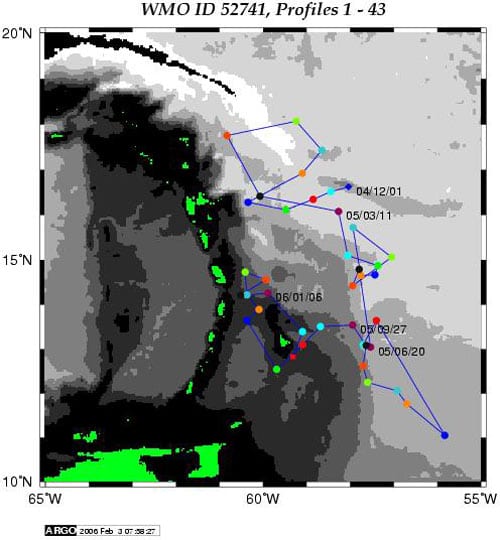

Valdes estimates that fewer than three floats a year go missing. Then, this winter, float 312 beached in the Bahamas, after traveling more than 1,000 nautical miles (1,850 kilometers) since its launch east of central Florida in June 2004. Float 393 ended up aboard a fishing boat off Barbados.

Valdes has subsequently pieced together their journeys. Before launch, every float is tagged for monitoring via satellite, so scientists do see where they are and where they shouldn’t be. Float 312, for example, began to concern physical oceanographer Breck Owens in late January. He saw on his computer screen at WHOI that it was making a beeline to land, likely tossed by currents into shallow water and then spit onto shore.

“I was pretty sure that it was going to be a loss,” Owens said. Then he received a surprise e-mail on Jan. 18 from a Canadian tourist who noticed the marooned float while snorkeling east of Andros Island.

She traced the float to WHOI’s Ocean Instruments website. Assured that it wasn’t dangerous, the tourist, Christine Yeomans of British Columbia, returned with a motorboat to collect the 80-pound instrument.

“My husband and I swam it back to the boat (no mean feat)!!!” Yeomans wrote in an e-mail. “Then he and our Bahamian guide pulled it into the boat. My husband unfortunately cracked his rib in the process. So we are hoping that this recovery will be somewhat useful and ‘not for naught.’ ”

Yeomans sent Valdes photos, which showed that float 312’s O-ring seal was compromised and had let seawater inside its pressure case. It was a goner. Valdes contacted a U.S. Navy acoustic test facility on Andros Island, which retrieved the instrument to dispose of it properly.

Float 393 had a happier fate. It was picked up 29 miles south of Barbados on Jan. 25 by a fisherman, Erwin Clark Breedyland. He made inquiries that eventually led back to Valdes.

Onshore, float 393 continued to transmit data, suggesting that it was intact and functioning, Valdes said. “I made arrangements for Breedyland to deploy the float 150 to 200 miles off Barbados on his next fishing trip.”

The research is funded by the Cooperative Institute for Climate and Ocean Research, a joint institute of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Slideshow

Slideshow

Christine and Leo Yeomans of British Columbia found float 312 while snorkeling east of Andros Island in the Bahamas. They contacted WHOI, recovered the float, and sent pictures that scientists will examine to see how the float was damaged, and why it beached. (Photo by Tria Giovan, Tria Giovan Photography)

Christine and Leo Yeomans of British Columbia found float 312 while snorkeling east of Andros Island in the Bahamas. They contacted WHOI, recovered the float, and sent pictures that scientists will examine to see how the float was damaged, and why it beached. (Photo by Tria Giovan, Tria Giovan Photography)- Jim Valdes, a WHOI engineer who designs and builds floats used for ocean research, estimates that fewer than three floats a year go missing. So he was "totally floored" when, in a single week, a tourist and a fisherman found two floats (similar to these in his lab) and contacted WHOI. (Photo by Amy Nevala, WHOI)

- Argo, a multi-national science observation program, provides data about the upper areas of the ocean using a fleet of floats dotting the globe. They spend most of their life at depth and surface to make the temperature and salinity profile measurements. The floats are contributed by many countries, but all data are freely available. (Illustration courtesy of the Argo Program/University of California at San Diego)

- Float 312 was launched several hundred miles east of Jacksonville, Fla. in June 2004. It floated more than 1,000 nautical miles before it beached in the Bahamas in January 2005. Colored dots show locations where it surfaced temporarily to transmit data via satellite. The blue line marks its track. (Illustration courtesy Breck Owens, WHOI)

- Float 393 was deployed west of the Virgin Islands and north of Barbados in December 2004. It circulated offshore the Lesser Antilles for about 1,000 nautical miles before it was picked up by a curious fisherman in late January, 29 miles south of Barbados. Colored dots show locations where it surfaced. The blue line marks its track. (Illustration courtesy Jim Valdes, WHOI)

Related Articles

- How WHOI helped win World War II

- Seeding the future

- New underwater vehicles in development at WHOI

- Learning to see through cloudy waters

- Five marine animals that call shipwrecks home

- Go with the flow

- Navigating new waters

- For Ben Santer, the fingerprints of the climate crisis are very human

- The 10,000-foot view

Topics

Featured Researchers

See Also

- WHOI Float Group

Formed in 1978 to support scientific research using neutrally buoyant drifters called floats - Ocean Instruments: How They Work, What They Do, and Why They Do It

A peek at WHOI's arsenal - The Argo Float Program