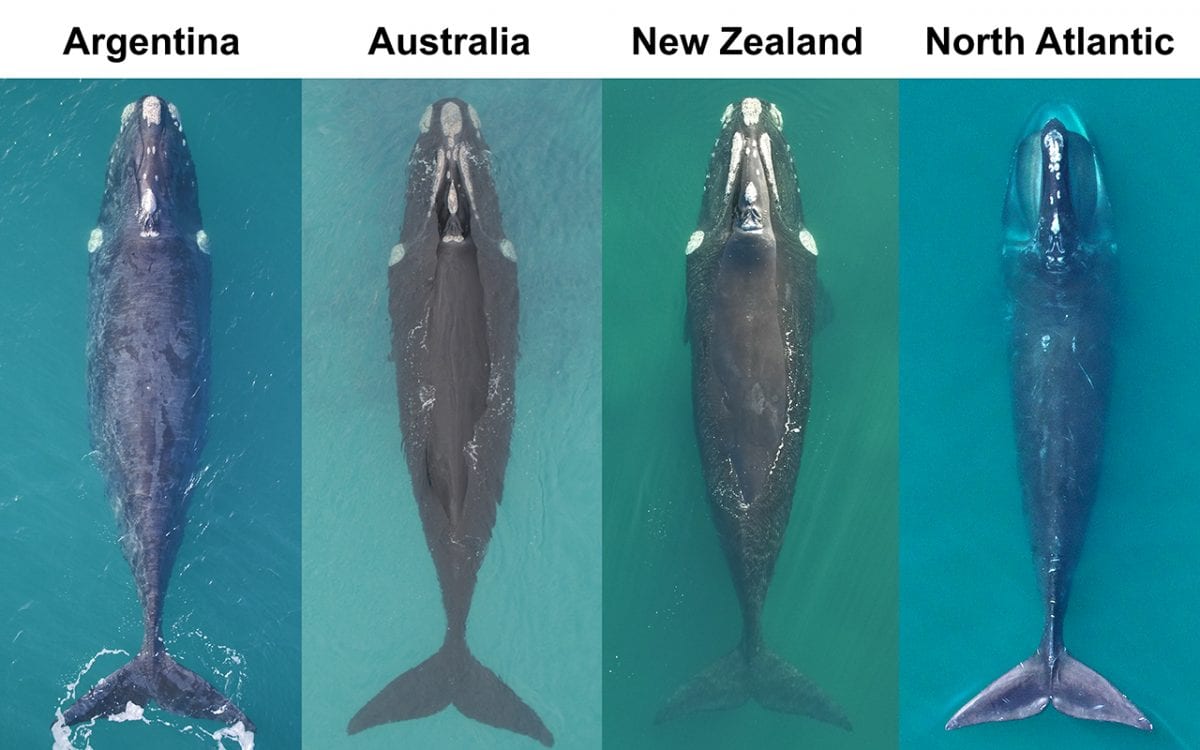

North Atlantic right whales are in much poorer condition than their Southern counterparts

Healthy southern right whales from three populations— (from left) Argentina, Australia and New Zealand— next to a much leaner North Atlantic right whale (right) in visibly poorer body condition. (Photos courtesy of: Fredrik Christiansen, Aarhus University; Stephen M. Dawson, University of Otago; and John W. Durban and Holly Fearnbach, NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center)

Healthy southern right whales from three populations— (from left) Argentina, Australia and New Zealand— next to a much leaner North Atlantic right whale (right) in visibly poorer body condition. (Photos courtesy of: Fredrik Christiansen, Aarhus University; Stephen M. Dawson, University of Otago; and John W. Durban and Holly Fearnbach, NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center) April 26, 2020

A new study by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) scientists and their colleagues reveals that endangered North Atlantic right whales are in much poorer body condition than their counterparts in the southern hemisphere. The international research team, led by Fredrik Christiansen from Aarhus University in Denmark, published their findings April 23, 2020, in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series.

Using drones and a method called aerial photogrammetry to measure the body length and width of individual right whales in four regions around the world, the team compared body condition of individual North Atlantic right whales with individuals from three increasing populations of Southern right whales: off Argentina, Australia and New Zealand.

From aerial photographs, the researchers estimated the body volume of individual whales, which they then used to derive an index of body condition or relative fatness. The analyses revealed that individual North Atlantic right whales—juveniles, adults and mothers—were all in poorer body condition than individual whales from the three populations of Southern right whales.

“For North Atlantic right whales as individuals, and as a species, things are going terribly wrong,” says WHOI researcher Michael Moore, a coauthor of the paper. “This comparison with their southern hemisphere relatives shows that most individual North Atlantic right whales are in much worse condition than they should be.”

Since the end of large-scale commercial whaling in the last century, most populations of Southern right whales have recovered well. Currently, there are about 10,000 to 15,000 southern right whales. In comparison, North Atlantic right whales are one of the world's most endangered large whale species, with a population of fewer than 400.

The study results are particularly alarming for the status of North Atlantic right whales, the researchers say, because good body condition and abundant fat reserves are crucial for their reproduction, as the animals rely on energy stores during the breeding season when they are mostly fasting. Stored fat reserves are important for mothers, who need the extra energy to support the growth of their newly born calf while they are nursing.

North Atlantic right whales spend most of their lives within 50 miles of the busy eastern coastline of North America, making them particularly vulnerable to human activities. More than half of these whales die in collisions with ships or by becoming entangled in fishing gear.

“Their decline has been so rapid that we know it’s not simply because not enough calves are being born—too many whales are also dying from human-caused injuries,” says Peter Corkeron of the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium.

Individual North Atlantic right whales have to cope with the energetic expense and other costs that are caused by frequent entanglements in fishing gear, in particular lobster and crab pots. These burdens, along with a change in the abundance and distribution of the rice-sized plankton that they eat, have left these whales thin and unhealthy.

“As a veterinarian, I’ve long been concerned about how entanglements affect the welfare of these whales,” adds Moore says. “Now we are starting to draw the linkages from welfare to this species’ decline. To reverse these changes, we must: redirect vessels away from, and reduce their speed in, right whale habitat; retrieve crab and lobster traps without rope in the water column using available technologies; and minimize ocean noise from its many sources.”

The study is the result of a collaborative effort by scientists from 12 institutions across five nations. The work was supported by: NOAA; the World Wildlife Fund for Nature Australia; a Murdoch University School of Veterinary and Life Sciences Small Grant Award; New Zealand Antarctic Research institute; Otago University; New Zealand Whale and Dolphin Trust; and National Geographic Society, Australia.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the ocean’s role in the changing global environment. For more information, please visit www.whoi.edu.

Key Takeaways

- Endangered North Atlantic right whales are in much poorer body condition than their counterparts in the southern hemisphere.

- Poor body condition affects the ability of North Atlantic right whales to reproduce. The population is also impacted by ship strikes, entanglements in fishing gear and a reduction in their food supply.

- This study is the largest assessment of the body condition of baleen whales in the world.