Microbes far beneath the seafloor rely on recycling to survive

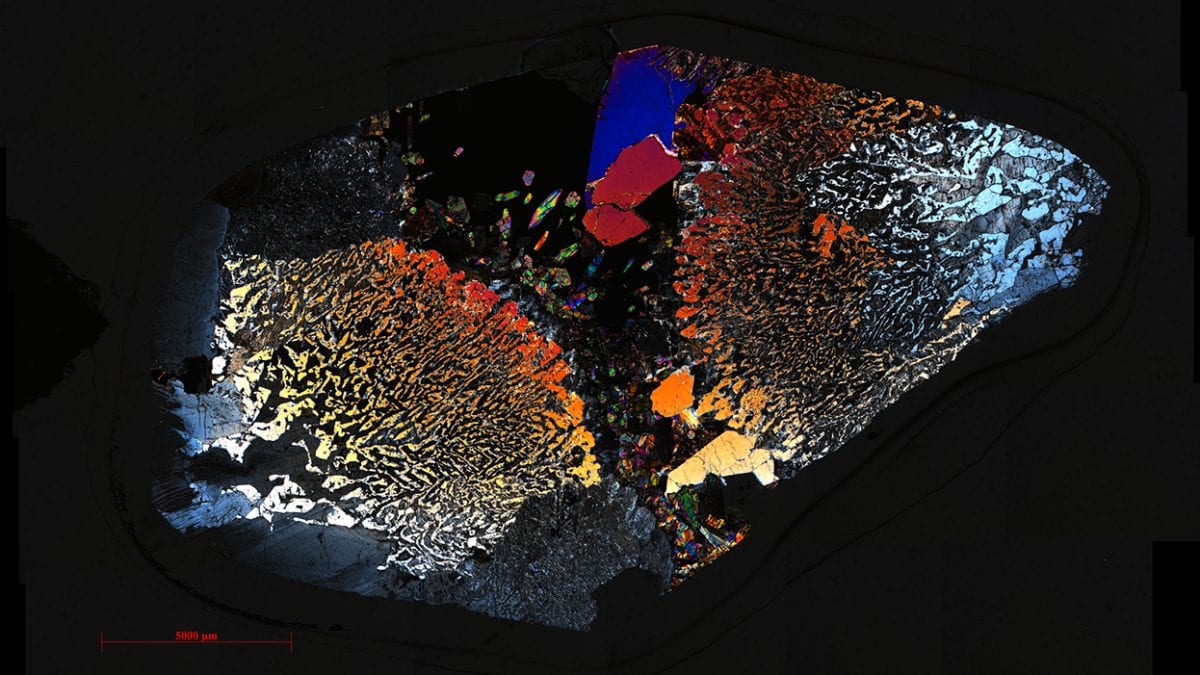

Detailed examination of rocks nestled thousands of feet beneath the ocean floor revealed life in plutonic rocks of the lower oceanic crust. Shown here is a thin section photomicrograph mosaic of one of the samples. (Photo by Frieder Klein, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Detailed examination of rocks nestled thousands of feet beneath the ocean floor revealed life in plutonic rocks of the lower oceanic crust. Shown here is a thin section photomicrograph mosaic of one of the samples. (Photo by Frieder Klein, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) March 11, 2020

Scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) reveal how microorganisms could survive in rocks nestled thousands of feet beneath the ocean floor in the lower oceanic crust, in a study published on March 11 in Nature. The first analysis of messenger RNA—genetic material containing instructions for making different proteins—from this remote region of Earth, coupled with measurements of enzyme activities, microscopy, cultures, and biomarker analyses provides evidence of a low biomass, but diverse community of microbes that includes heterotrophs that obtain their carbon from other living (or dead) organisms.

“Organisms eking out an existence far beneath the seafloor live in a hostile environment,” says Dr. Paraskevi (Vivian) Mara, a WHOI biochemist and one of the lead authors of the paper. Scarce resources find their way into the seabed through seawater and subsurface fluids that circulate through fractures in the rock and carry inorganic and organic compounds.

To see what kinds of microbes live at these extremes and what they do to survive, researchers collected rock samples from the lower oceanic crust over three months aboard the International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 360. The research vessel traveled to an underwater ridge called Atlantis Bank that cuts across the Southern Indian Ocean. There, tectonic activity exposes the lower oceanic crust at the seafloor, “providing convenient access to an otherwise largely inaccessible realm,” write the authors.

Researchers combed the rocks for genetic material and other organic molecules, performed cell counts, and cultured samples in the lab to aid in their search for life. “We applied a completely new cocktail of methods to really try to explore these precious samples as intensively as we could,” says Dr. Virginia Edgcomb, a microbiologist at WHOI, the lead PI of the project, and a co-author of the paper. “All together, the data start to paint a story.”

Key Takeaways

- Scientists collected rock samples from the lower oceanic crust down to 2,400 feet beneath the ocean floor in search of life.

- In the first analysis of genetic material from this region to uncover how organisms might survive, researchers provide evidence that microbes efficiently recycle and store available organic compounds.

- Genetic material suggests that many lower crust microbes cannot produce their own food and rely on carbon found in the environment to obtain energy.

- These findings provide a more complete picture of carbon cycling by illuminating biologic activity deep below the planet’s surface.

By isolating messenger RNA and analyzing the expression of genes—the instructions for different metabolic processes—researchers showed evidence that microorganisms far beneath the ocean express genes for a diverse array of survival strategies. Some microbes appeared to have the ability to store carbon in their cells, so they could stockpile for times of shortage. Others had indications they could process nitrogen and sulfur to generate energy, produce Vitamin E and B12, recycle amino acids, and pluck out carbon from hard-to-breakdown compounds called polyaromatic hydrocarbons. “They seem very frugal,” says Edgcomb.

This rare view of life in the far reaches of the earth extends our view of carbon cycling beneath the seafloor, Edgcomb says. “If you look at the volume of the deep biosphere, including the lower oceanic crust, even at a very slow metabolic rate, it could equate to significant amounts of carbon.”

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation.The research team also included colleagues from Tongji University, University of Bremen, Texas A&M University, Université de Brest, and Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the ocean’s role in the changing global environment. For more information, please visit www.whoi.edu.