New study takes comprehensive look at marine pollution

New study appearing in the December 3, 2020, issue of Annals of Global Health finds the marine plastics, one of several forms of ocean pollution worldwide, is increasing at a rate of 10 million metric tons per year. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

New study appearing in the December 3, 2020, issue of Annals of Global Health finds the marine plastics, one of several forms of ocean pollution worldwide, is increasing at a rate of 10 million metric tons per year. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) December 3, 2020

Paper finds ocean pollution is a complex mix of chemicals and materials, primarily land-based in origin, with far-reaching consequences for environmental and human health, but there are options available for world leaders

For centuries, the ocean has been viewed as an inexhaustible receptacle for the byproducts of human activity. Today, marine pollution is widespread and getting worse and, in most countries, poorly controlled with the vast majority of contaminants coming from land-based sources. That’s the conclusion of a new study by an international coalition of scientists taking a hard look at the sources, spread, and impacts of ocean pollution worldwide.

The study is the first comprehensive examination of the impacts of ocean pollution on human health. It was published December 3 in the online edition of the Annals of Global Health and released the same day at the Monaco International Symposium on Human Health & the Ocean in a Changing World, convened in Monaco and online by the Prince Albert II de Monaco Foundation, the Centre Scientifique de Monaco and Boston College.

“This paper is part of a global effort to address questions related to oceans and human health,” said Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) toxicologist and senior scientist John Stegeman who is second author on the paper. “Concern is beginning to bubble up in a way that resembles a pot on the stove. It’s reaching the boiling point where action will follow where it’s so clearly needed.”

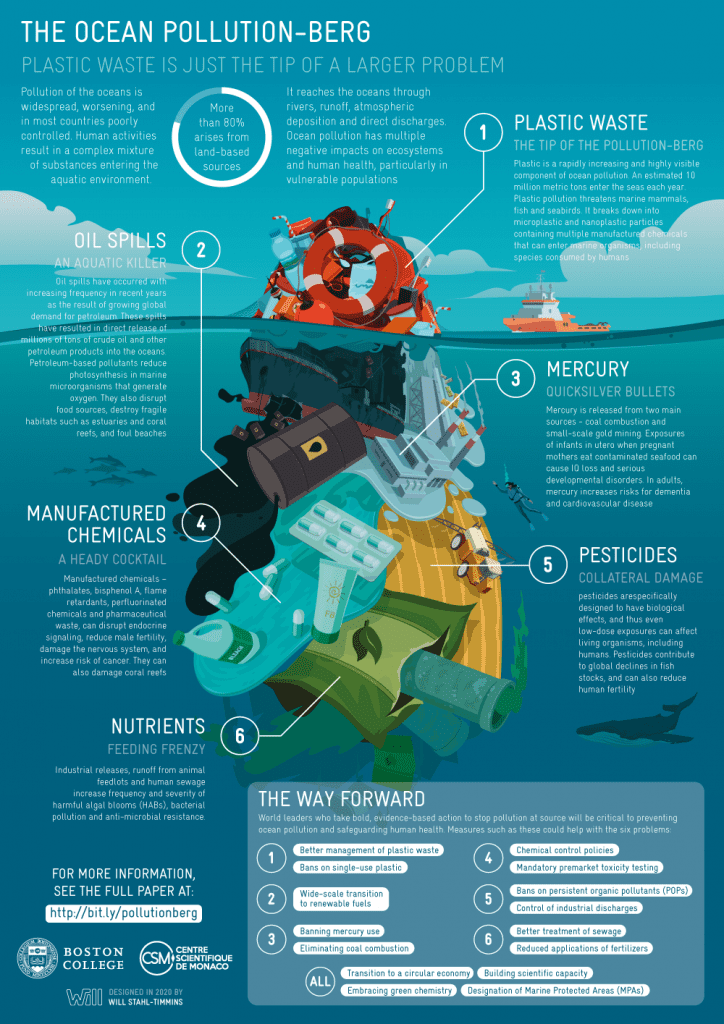

Despite the ocean’s size—more than two-thirds of the planet is covered by water—and fundamental importance supporting life on Earth, it is under threat, primarily and paradoxically from human activity. The paper, which draws on 584 peer-reviewed scientific studies and independent reports, examines six major contaminants: plastic waste, oil spills, mercury, manufactured chemicals, pesticides, and nutrients, as well as biological threats including harmful algal blooms and human pathogens.

It finds that ocean chemical pollution is a complex mix of substances, more than 80% of which arises from land-based sources. These contaminants reach the oceans through rivers, surface runoff, atmospheric deposition, and direct discharges and are often heaviest near the coasts and most highly concentrated along the coasts of low- and middle-income countries. Waters most seriously impacted by ocean pollution include the Mediterranean Sea, the Baltic Sea, and Asian rivers. For the many ocean-based ecosystems on which humans rely, these impacts are exacerbated by global climate change. According to the researchers, all of this has led to a worldwide human health impacts that fall disproportionately on vulnerable populations in the Global South, making it a planetary environmental justice problem, as well.

In addition to Stegeman, who is also director of the NSF- and NIH-funded Woods Hole Center for Oceans and Human Health, WHOIbiologists Donald Anderson and Mark Hahn, and chemist Chris Reddy also contributed to the report. Stegeman and the rest of the WHOI team worked on the analysis with researchers from Boston College’s Global Observatory on Pollution and Health, directed by the study’s lead author and Professor of Biology Philip J. Landrigan, MD. Anderson led the report’s section on harmful algal blooms, Hahn contributed to a section on persistent organic pollutants (POPs) with Stegeman, and Reddy led the section on oil spills. The Observatory, which tracks efforts to control pollution and prevent pollution-related diseases that account for 9 million deaths worldwide each year, is a program of the new Schiller Institute for Integrated Science and Society, part of a $300-million investment in the sciences at BC. Altogether, over 40 researchers from institutions across the United States, Europe and Africa were involved in the report.

In an introduction printed in Annals of Global Health, Prince Albert of Monaco points out that their analysis, in addition to providing a global wake-up, serves as a call to mobilize global resolve to curb ocean pollution and to mount even greater scientific efforts to better understand its causes, impacts, and cures.

“The link between ocean pollution and human health has, for a long time, given rise to very few studies,” he says. “Taking into account the effects of ocean pollution—due to plastic, water and industrial waste, chemicals, hydrocarbons, to name a few—on human health should mean that this threat must be permanently included in the international scientific activity.”

The report concludes with a series of urgent recommendations. It calls for eliminating coal combustion, banning all uses of mercury, banning single-use plastics, controlling coastal discharges, and reducing applications of chemical pesticides and fertilizers. It argues that national, regional and international marine pollution control programs must extend to all countries and where necessary supported by the international community. It calls for robust monitoring of all forms of ocean pollution, including satellite monitoring and autonomous drones. It also appeals for the formation of large, new marine protected areas that safeguard critical ecosystems, protect vulnerable fish stocks, and ultimately enhance human health and well-being.

Most urgently, the report calls upon world leaders to recognize the near-existential threats posed by ocean pollution, acknowledge its growing dangers to human and planetary health, and take bold, evidence-based action to stop ocean pollution at its source.

“The key thing to realize about ocean pollution is that, like all forms of pollution, it can be prevented using laws, policies, technology, and enforcement actions that target the most important pollution sources,” said Professor Philip Landrigan, MD, lead author and Director of the Global Observatory on Pollution on Health and of the Global Public Health and the Common Good Program at Boston College. “Many countries have used these tools and have successfully cleaned fouled harbors, rejuvenated estuaries, and restored coral reefs. The results have been increased tourism, restored fisheries, improved human health, and economic growth. These benefits will last for centuries.”

The report is being released in tandem with the Declaration of Monaco: Advancing Human Health & Well-Being by Preventing Ocean Pollution, which was read at the symposium’s closing session. Endorsed by the scientists, physicians and global stakeholders who participated in the symposium in-person and virtually, the declaration summarizes the key findings and conclusions of the Monaco Commission on Human Health and Ocean Pollution. Based on the recognition that all life on Earth depends on the health of the seas, the authors call on leaders and citizens of all nations to “safeguard human health and preserve our Common Home by acting now to end pollution of the ocean.”

“This paper is a clarion call for all of us to pay renewed attention to the ocean that supports life on Earth and to follow the directions laid out by strong science and a committed group of scientists,” said Rick Murray, WHOI Deputy Director and Vice President for research and a member of the conference steering committee. “The ocean has sustained humanity throughout the course of our evolution—it’s time to return the favor and do what is necessary to prevent further, needless damage to our life planetary support system.”

Funding for this work was provided in part by the U.S. Oceans and Human Health Program (NIH grant P01ES028938 and National Science Foundation grant OCE-1840381), the Centre Scientifique de Monaco, the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation, the Government of the Principality of Monaco, and Boston College.

###

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate an understanding of the ocean’s role in the changing global environment. WHOI’s pioneering discoveries stem from an ideal combination of science and engineering—one that has made it one of the most trusted and technically advanced leaders in basic and applied ocean research and exploration anywhere. WHOI is known for its multidisciplinary approach, superior ship operations, and unparalleled deep-sea robotics capabilities. We play a leading role in ocean observation, and operate the most extensive suite of data-gathering platforms in the world. Top scientists, engineers, and students collaborate on more than 800 concurrent projects worldwide—both above and below the waves—pushing the boundaries of knowledge and possibility. For more information, please visit www.whoi.edu