Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Maps Ancient Greek Shipwreck

February 2, 2006

Additional contact:

Denise Brehm

MIT News Office

617-253-2704

brehm@mit.edu

After lying hidden for millennia off the coast of Greece, a sunken 4th century B.C. merchant ship and its cargo have been surveyed by an international team using a robotic underwater vehicle. The group accomplished in two days what it would take divers years to do. The project, the first in a new collaboration between U.S. and Greek researchers, demonstrates the potential of new technology and imaging capabilities to rapidly advance marine archaeology.

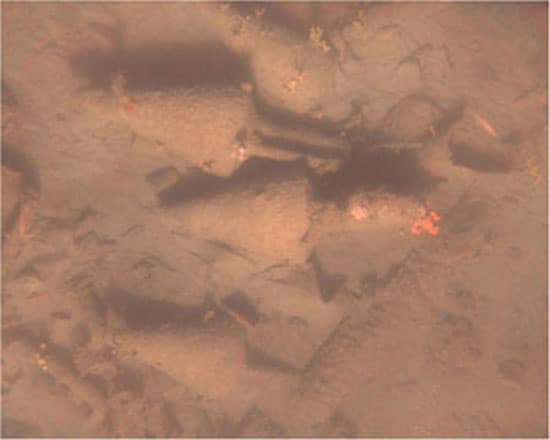

Greek scientists and archaeologists discovered the ancient shipwreck in 2004 during a sonar survey. The wooden Greek merchant ship sank between Chios and Oinoussia islands in the eastern Aegean Sea in 60 meters (about 200 feet) of water, too deep for conventional SCUBA diving. The most visible remains of the shipwreck are its cargo of 400 ceramic jars, called amphoras. Team archaeologists believe the amphoras probably contained wine and olive oil.

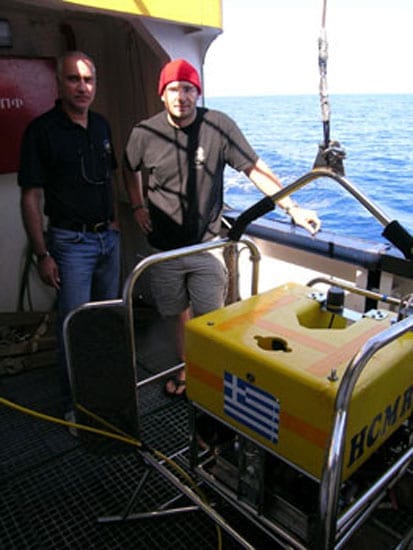

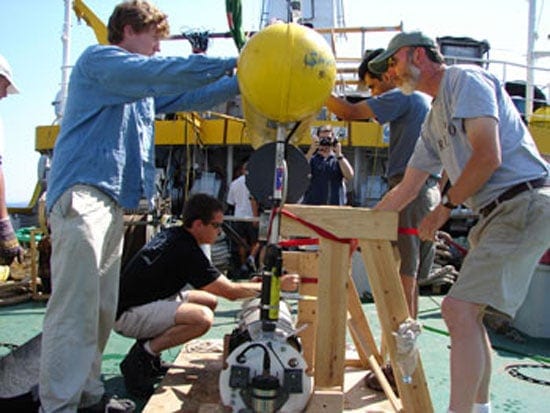

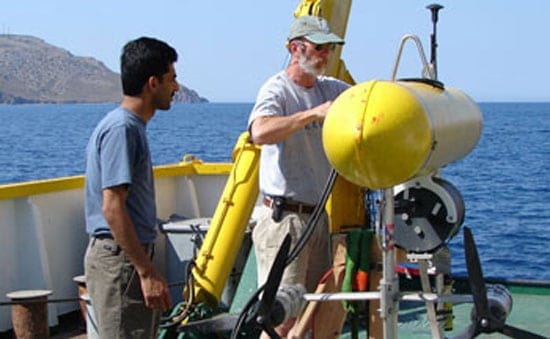

Forgotten for more than two thousand years, the ship might never have revealed its clues to ancient Greek culture until a research team from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the Greek Ministry of Culture, and the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR) joined forces. Using a novel autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) named SeaBED developed and operated by WHOI, the team made a high-precision photometric survey of the site using techniques developed by WHOI and MIT researchers over the past eight years.

Hanumant Singh and team at the WHOI Deep Submergence Laboratory (DSL) designed and built SeaBED. DSL has been a leader in developing and building submersible robotic vehicles for a variety of underwater environments, including the towed ARGO vehicle that found the wrecks of Titanic and Bismarck and the JASON II remotely operated vehicle that explores the seafloor today.

The Chios wreck survey demonstrates how advanced technology can dramatically change the field of underwater archeology, said WHOI deepwater archaeologist Brendan Foley.

For a single three-hour dive, SeaBED was programmed to “fly” over the shipwreck site in precisely spaced tracks. Multibeam sonar completely mapped the wreck while a digital camera collected thousands of high-resolution images. The vehicle took 7,650 images on four dives to reveal the ship’s ceramic cargo and marine life, including bright yellow sponges and colorful fish. The vehicle never touched the wreck, leaving it in an undisturbed state, important for future studies.

Robotic technology is the only way to reach deep shipwrecks like the one at Chios, but the systems can also be applied to shallower sites.

Most human diving time on archaeological sites is consumed with basic mapping tasks. Typically it takes hundreds of diving hours over several years to make a site plan using tape measures and clipboards. The new robotic techniques produce results very quickly. Robotic vehicles can map and create a photomosaic of a site with quantifiable accuracy in as little as a few hours.

As soon as SeaBED brought the first images from the Chios wreck to the surface, project archaeologists began interpreting the data. The images were assembled into mosaics that depict minute features of the shipwreck with unmatched clarity and detail.

“By using this technology, diving archeologists will be freed from routine measuring and sketching tasks, and instead can concentrate on the things people do better than robots: excavation and data interpretation,” contends Singh, an engineering and imaging scientist. “With repeated performances, we’ll be able to survey shipwrecks faster and with greater accuracy than ever before.”

The historic value in ships,such as the Chios wreck is the information they provide about ancient trade networks. The wreck is “like a buried UPS truck,” said David Mindell, a professor of engineering history and systems at MIT. “It provides a wealth of information that helps us figure out networks based on the contents of the truck.”

The island of Chios was famous throughout the Classical Greek world for its wine. Athens was its largest customer, but Chios sold its products in markets as far flung as the Crimea and Cyprus. Foley said the wreck’s cargo is the largest assemblage of Chian amphoras found to date, and provides valuable data about the volume of ancient trade. The team’s 2005 survey showed that despite the turmoil of the Peloponnesian War and subsequent break-up of the Athenian empire, Chios was still engaged in trade in the 4th century B.C.

“Our technologies allow us to learn about the past in ways that we couldn’t achieve otherwise,” Foley said. “We’re not looking for footnotes any more. We’re looking to write new chapters, and are convinced that in 10 to 15 years using these methods, we will have changed history.”

The team’s research program is scheduled to last ten years or more and is focused on uncovering sites dating to the dawn of civilization in the Mediterranean: the Bronze Age (2500 to 1200 B.C.), and Minoan and Mycenaean cultures and their trading partners.

“We’re looking forward to continuing the project next summer,” HCMR geologist Dimitris Sakellariou said. “We will be exploring many more sites using new chemical sensors to collect environmental data about the shipwrecks, something that has not been done before. It is a very exciting collaboration. ”

In addition to Foley, Singh, and Mindell, the American team for the Chios expedition included Brian Bingham of Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering; Richard Camilli, Ryan Eustice, and Chris Roman from WHOI; and David C. Switzer of Plymouth State University. HCMR geologist Dimitris Sakellariou led the Greek science and technical team, while Katerina Delaporta, Director of the Ministry of Culture’s Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, headed the Greek archaeology team.

The team presented preliminary results at the November 2005 American Schools of Oriental Research conference in Philadelphia.