Study Looks at Gray Seal Impact on Beach Water Quality

December 18, 2012

Scientists from the newly created Northwest Atlantic Seal Research Consortium (NASRC) are using data collected by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) to investigate whether seals may impact beach water quality along Outer Cape Cod.

A growing population of gray seals has been cited as the reason for beach closures due to poor water quality on the outer Cape. But is there evidence to support these water quality statements?

“We took some basic steps to assess whether there is cause for concern,” said Rebecca J. Gast, an associate scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and member of the NASRC. “As far as I know, no one has looked at the data to ask these questions before.”

The precise number of gray seals in the area is not known; however, over the last 30 years, in areas where there were once a few hundred, there are now several thousand.

There are three sites or “haul-outs” on the lower Cape where large numbers of gray seals leave the water to avoid predators, regulate their body temperature, and socialize. Sites in the area that host several hundred seals at low tide include High Head on the outer Cape in the National Seashore/Truro area; Jeremy Point on the Cape Cod Bay side of Wellfleet; and North Island in Chatham (see list of beaches).

To conduct their analysis, the researchers examined water quality data from 89 sites at public beaches in six surrounding towns including Provincetown, Truro, Wellfleet, Eastham, Orleans, and Chatham. The water samples, which were collected and analyzed by the MDPH between 2003 and 2012, measure levels of the Fecal Indicator Bacteria (FIB) enterococci, a group of bacterial species which are typically found in human and animal intestines and feces. Although most enterococci do not typically cause illness in humans, it is used to indicate the possible presence of other disease-causing organisms associated with fecal contamination.

In marine waters, the accepted level of enterococci for a single water sample is 104 colony forming units per 100 milliliters (cfu/100 ml) of bathing water or below. Any sample with a count greater than 104 cfu/100 ml is called an “exceedance,” and signs are posted at the beach to warn the public against recreational use of the water.

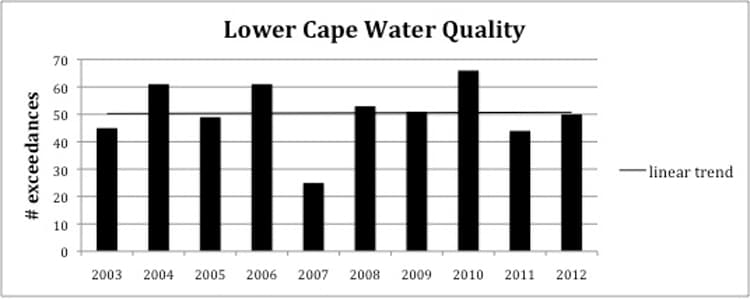

“Our first task was to examine the total number of exceedance events each year for the lower Cape region,” says Gast, “so we could determine whether there was a trend towards increased closures which would suggest a decline in water quality.”

“Bathing beach water quality is highly variable from year to year, and our analysis of 10 years of data shows there was no change in the trend of water quality exceedances for the region,” continues Gast. “That being said, there are differences in water quality trends when you look at the individual towns.”

Armed with this overview of the state of water quality in the six towns, the researchers went on to examine whether the beaches closest to large seal haul-outs had more closures due to FIB than other beaches.

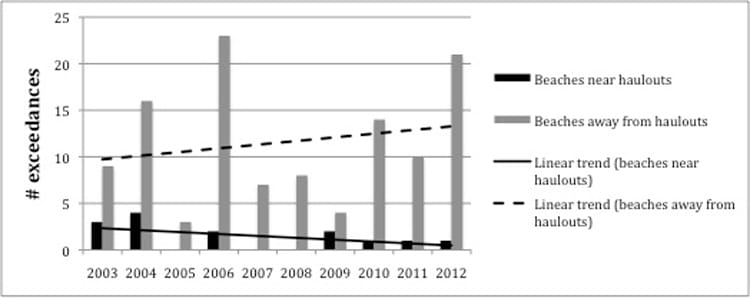

“We divided the beaches in the lower Cape region into those within 5 miles of seal haul-outs, and those more than 5 miles from seal haul-outs. This distance was chosen to represent what we thought would be a reasonable distance for the dispersion and inactivation of FIB on a daily tidal schedule,” Gast explains.

The analysis found the beaches near the haul-outs actually showed a decreasing trend in yearly FIB exceedance events over the last decade, while the beaches away from seal haul-outs showed an increasing trend in beach postings due to FIB.

“The evidence indicates that at this time, the water quality at beaches near large seal haul-outs is not worse than at beaches without large numbers of seals nearby,” concludes Gast. “In fact, 4 of the 5 beaches in Chatham Harbor that are close to the seal haul-outs have never had an FIB exceedance event.”

Members of the NASRC will continue to assess and monitor the effects of seal populations on the ecology and economy of the region. Research that would be useful includes continued monitoring of water quality at/near haul-out beaches, models of predominant water current directions and speeds in the area to better assess bacterial dispersion and transport, and development of quantitative fecal source tracking methods for seals. The researchers are looking for funds to do this work.

The Northwest Atlantic Seal Research Consortium, an alliance of scientists, fishers, and resource managers, was recently created to help with concerns about increasing seal populations along the New England coast and their interaction with local fisheries. For more information please contact sealresearch@whoi.edu.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the ocean’s role in the changing global environment.