A Robot Is Resurrected at Sea

Engineers rebuild damaged deep-sea vehicle and complete mission

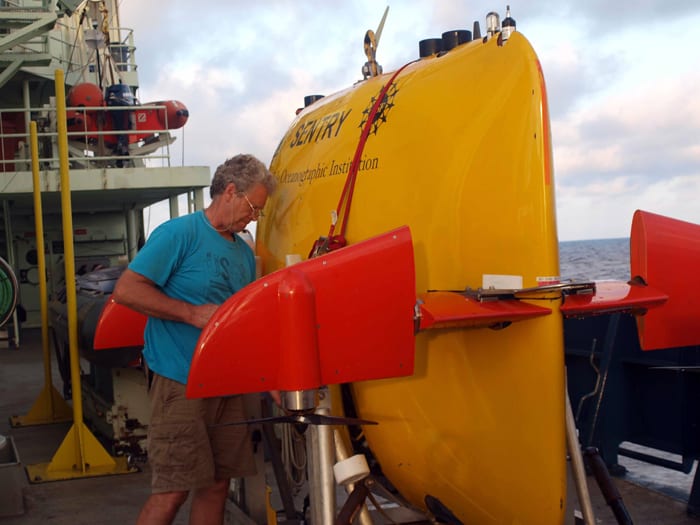

Barely a month after the undersea robot ABE imploded and was lost in the depths, ABE’s “son,” Sentry, suffered fire and flooding that destroyed critical internal components. But a team of engineers rallied to rebuild its electronics at sea and put the vehicle back in the water in four days.

Sentry was deployed from the research vessel Atlantis near the Galápagos Islands on April 4 and was descending for a routine night of seafloor mapping when engineers noticed it was heading straight to the bottom instead of starting its mission. Minutes later, at about 1,700 meters, the vehicle’s emergency controllers kicked in, releasing drop weights to allow Sentry to rise to the surface for an early recovery.

“When it came to the surface, it was stone-cold dead,” said Dana Yoerger, a scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), who helped design Sentry. “We knew there could be a big problem.”

WHOI engineers found seawater in Sentry’s main housing. Rod Catanach, the Sentry team’s mechanical engineer, carefully inspected the vehicle and diagnosed the cause: A pinhole fracture in a cable connector allowed seawater into the housing. It not only flooded the equipment, it also sparked a fire amid the electronics. Catanach assessed the damage. He thought Sentry could be fixed and began to disassemble the robot.

Sentry’s power circuits and motherboards were destroyed, but the damage was contained in the main housing because the robot’s batteries automatically shut down, Yoerger said. The damage would necessitate a complete refit by WHOI electrical engineer Al Duester.

“Unfortunately—but in this case, fortunately—Al has plenty of experience working with water-damaged electronics,” Yoerger said. “His expertise was critical.”

No one in the group could estimate how long the refit might take, even if they had all the parts on board needed to repair Sentry.

“There’s no Radio Shack helicopter that will fly out and drop off fresh supplies, even if you can order them online from a ship these days,” said Chris German, chief scientist for deep submergence at WHOI. “When you have a problem, you have to fix it based on what you have out there with you.”

Working nearly nonstop, Duester used spare parts on board and cleaned up what he could to use again, Yoerger said.

“There was a moment when this was taken apart and he said to me, ‘It took me three years to build this. How can I put it back together in a week?’ ” Yoerger said. “He put it back together in two days.”

“The guys in the Alvin (submersible) Group gave us their ultrasonic cleaner—we couldn’t have done it without that,” said Duester. “And Marshal Swartz, who was on the cruise to operate the TowCam (a towed camera system) pulled out all the stops helping us,” working hours to clean and rinse parts as Duester disassembled them.

After another day of testing and tweaking, the Sentry team—Yoerger, Duester, Catanach, Scott McCue, and graduate student Jordan Stanway—had Sentry working again. Catanach reassembled the vehicle in hours, a task that ordinarily takes days, and Sentry was back in the water, working as if the fire and flood had never happened. Sentry completed five more dives.

“The near-catastrophe did not prevent us from achieving our goals,” Yoerger said.

“It’s incredible, and it wasn’t luck—it was the people who had the wherewithal and knowledge to rebuild a complicated machine,” said the expedition’s chief scientist, John Sinton, a geologist from the University of Hawaii. “I had a lot of confidence that whatever problems they had, they could deal with. They’re the best there is.”

The near-miss came one month after the loss of the Autonomous Benthic Explorer known as ABE off the coast of Chile. WHOI engineers believe ABE, built in the early 1990s, was lost when glass spheres used to keep the vehicle buoyant imploded catastrophically while the robot was at the bottom of the sea.

Designed as ABE’s successor, Sentry is only two years old and has newer technology. Instead of glass spheres, for example, it uses a material called syntactic foam, which cannot implode.

Sentry is an unmanned, untethered vehicle programmed to swim on its own on missions in the deep. It is equipped with a sophisticated bathymetric mapping tool and state-of-the-art sonar and navigational devices. It can be outfitted with a variety of sensors to measure properties in seawater and on the seafloor, and camera and lighting systems.

Scientists aboard Atlantis used Sentry to map the seafloor around the Galápagos Spreading Center, a mid-ocean ridge near the Galápagos Islands in the Pacific Ocean. Despite the setback, scientists were pleased with the high-resolution seafloor maps that the vehicle brought in.

“When we’re mapping the seafloor [with Sentry], we’re basically removing the water,” said Scott White, a geologist from the University of South Carolina. It’s like “letting the sun shine on this part of the world we’ve never seen before, and now we’re able to see it for the first time.”

Sentry’s next mission, mapping along the Juan de Fuca Ridge off the Pacific Northwest, is scheduled for August.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- After the autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry was flooded by seawater that sparked a fire, Rod Catanach, the Sentry team’s mechanical engineer, carefully inspected the vehicle and diagnosed the cause: A pinhole fracture in a cable connector allowed seawater into the housing. He disassembled and reassembled the vehicle to repair it and get it operational again within days.

- The flooding and fire destroyed most of Sentry's electronic systems. Working nearly nonstop, Al Duester, an engineer on the WHOI Sentry team, rebuilt the entire system in two days, salvaging and repairing what he could and using spare parts available on the ship.

Related Articles

Featured Researchers

See Also

- AUV Sentry

- A Robot Starts to Make Decisions on its Own from Oceanus magazine

- A New Deep-Sea Robot Called Sentry from Oceanus magazine

- R.I.P. A.B.E. from Oceanus magazine

- Dana Yoerger